Memento mori: A Middle English Halloween

31 October 2021

Would you like to hear a Middle English ghost story? ASE’s Lorna Webb has been reading some particularly seasonal medieval literature and thinking about themes of ghost stories, monsters, spirits and reflecting on the mortality of man…

Introduction

People in medieval Britain would scarcely recognise our modern signatures of Halloween, yet reflecting on the nature of death has been a central theme of this time of year for hundreds, if not thousands of years.

Halloween originally derived from the festival of Samhain, where people would light bonfires and wear costumes to ward off ghosts. Through the centuries it was combined with Roman and later Christian festivals, eventually morphing into the Halloween celebrations of today.

Rather than pumpkins and trick or treating, the Halloween-esque literature of the medieval period focusses on themes such as ghost stories, monsters, spirits and reflecting on the mortality of man. Bede records phantoms or ghost sightings in his saint hagiologies (Joynes 2001:12), and let’s not forget the monster from Beowulf, Grendel, described as in conflict with God and the teachings of early Christianity (Mellinkoff 1979:143). By linking medieval monsters to evil or sinful biblical figures, the early church attempted to make sense of traditional customs from a Christian point of view.

Remember that you die...

As the centuries of Christianity continued, the Old English ‘pagan’ monsters and ghosts became the mysteries of death and mortality (Klinck 2020: 66).

This is understandable. The medieval period had many horrible, untreatable diseases, high infant mortality, and low life expectancy. With death surrounding and walking side by side with the peoples of the time it is no wonder that the concept of memento mori becomes an important aspect in the literature and art of the time.

Memento mori is Latin and means “remember that you die”. The concept is symbolised in the poetry and art that appears at the time (Hughes 2012), and is understandably more pronounced during and immediately after the Black Death in the fourteenth century.

A good example of this is the tomb of Thomas Gooding in Norwich Cathedral. This curious upright tomb is found on one of the walls with a brass carving of a skeleton. The skeleton bears this fantastic inscription (Hughes 2012).

All you that do this place pass bye

Remember death for you will dye.

As you are now even so was I

And as I am so shall you be.

Thomas Gooding here do staye

Wayting for God's judgement day

The inscription makes the reader both reflect upon their mortality and ponder the person who had the inscription made - a classic memento mori.

The middle English period has many examples of this, including one tale of three dead kings…

The Three Dead Kings

The Three Dead Kings is a great example of a Middle English ghost story dealing with the concept of memento mori. It is an alliterative poem found in a late fifteenth century manuscript held in the Bodleian Library (Fein 2002:70).

So, grab your pumpkin spiced latte... and I’ll begin.

Three kings are hunting boar in the forest when they are separated from their group by a mist.

Out of the mist appears before them three phantoms, walking corpses in various states of decomposition (lines 43-45). The phantoms, forefathers of the living kings, complain to the terrified trio that they do not say enough masses for the dead (lines 103-107).

The three phantom kings explain to the living kings that they were pleasure loving in life, and also did not say prayers for the dead or believe in the word of Jesus. They lived unrepentant lives and now they suffer for it (lines 106- 112).

The phantoms thus represent the fate that awaits the living kings, as the theme of memento mori makes itself known to remind us that all men die (lines 120-121).

““Makis your merour be me! My myrthus bene mene: Wyle I was mon apon mold, morthis thai were myne”

“Make me your mirror! My joy now means nothing. While I was man upon the earth, mortal sin was mine.”

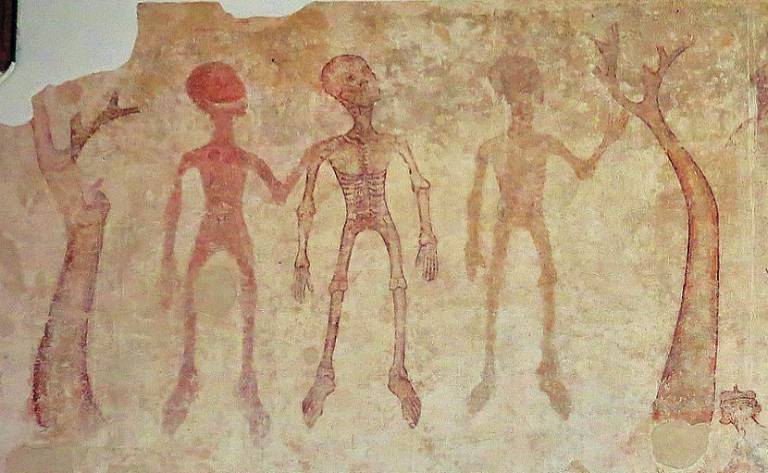

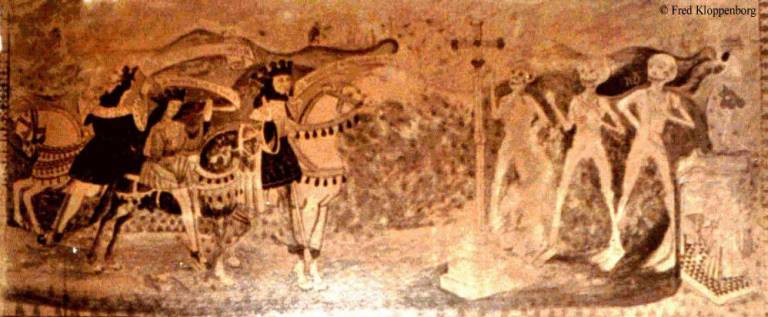

The dawn comes, notably the red rays of morning, and the phantoms depart. The poem ends with the three living kings returning to the minister, saying mass and having the tale drawn on the wall of the church (lines 137-143). This reflects actual paintings of the tale which do appear from the 14th century on church walls, like the below from Belton, Suffolk. You can find a list of English examples here - and the image at the start of the blog is another of these.

This story contains many themes common to medieval literature, and some aspects of medieval life that require further explanation.

The Woodland

This is a common trope in medieval literature, a boar hunt derived from a French theme “chanson d'aventure” (Marvin 2006) and the forest setting, usually a place for magic and adventure. In Arthurian tales from the high medieval period, such as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Le Morte d’Arthur, the woodland represents the unknown, and a liminal place outside the laws of civilisation. This is seen again in Three Dead Kings, highlighting the “other worldliness” and how the laws of nature are suspended with the background of the forest.

A Requiem Mass

The main gripe the three dead kings have with the three living kings is that they do not say enough masses for the dead. This is important in medieval Catholicism as saying prayers and masses for the dead would shorten their time in Purgatory.

A mass for the dead is called a Requiem Mass, known in plain chant through the medieval period the earliest surviving requiem mass in a polyphonic setting dates to the fifteenth century. These are now performed as concert pieces with famous versions by composers such as Faure, Verdi and Mozart (though there are questions over his authorship) are still very popular. You can listen to Mozart’s haunting requiem here.

Memento Mori

Remember that you die… In the story when faced with the three phantoms the three living kings are both confronted with their own mortality and the inescapable physical manifestation of their futures. The three dead kings appear in some versions of the tale in shrouds, as skeletons, in various forms of decomposition and in one case one of the dead kings brings his coffin with him. The idea of the living kings seeing their future afterlives with their earthy remains decaying and being reminded that all life ends gives the story an extra dimension by showing the phases of death and burial.

Conclusion

Themes of memento mori can be found in many cultures of the world today. For example, in Mexico they celebrate the Day of the Dead or Día de los Muertos. This is a holiday which is celebrated on the 1st November and involves gatherings of friends and family to celebrate and pay respects to friends and family who have died. It is celebrated by building brightly coloured alters to the deceased, food is both offered to the dead and consumed including chocolate and sugar skulls. Gifts are also received including tequila for adults. This celebration of the dead, which uses depictions of skeletons is a modern form of remembrance. The 2017 Disney Film Coco depicts the Day of the Dead and deals with themes of death and loved ones who have passed on. It does not hide from memento mori (even though it is a children’s film) and instead reinforces the idea of celebrating both life and death and to not forget those who have died.

In Britain at least, our Halloween festival is shortly followed by a day of remembering – Armistice Day on the 11th November. In a way the focus of remembering the dead has moved to this event. In the classical music world it is not uncommon for Choral societies to perform a setting of a Requiem Mass this time of year. A modern example of these events crossing over is Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem which is a mass setting but also uses the poetry of the First World War. War Requiem was written for the rebuilding of Coventry Cathedral and shares the act of remembrance and the finality of the present. This transitional nature is fitting for Halloween and would have resonated with those in the medieval period as a good ghost story does today…

References

Fein S., 2002. Life and Death, Reader and Page: Mirrors of Mortality in English Manuscripts. Mosaic: An interdisciplinary CRITICAL Journal. 35 (1) 69-94

Hughes W., 2012. Historical Dictionary of Gothic Literature. Scarecrow Press.

Joynes A., 2001. Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Medieval Ghost Stories: An anthology of Mriacles, Marvels and Prodigies. Boydell and Brewers; Boydell Press. 12-15.

Klinck A., 2020. Poems on Mortality. The Voices of Medieval English Lyric: An Anthology of Poems ca 1150-1530. 66-92.

Marvin W., 2006. Hunting Law and Ritual in Medieval English Literature. Boydell & Brewer, D. S. Brewer

Mellinkoff R., 1979. Cain’s monstrous progeny in “Beowulf”: part 1, Noachic tradition. Anglo- Saxon England (8) 143-162.

For the entire poem of the Three Dead Kings click here.

Cover image: The Three Dead, part of a 14th century painting on the walls of Wickhampton Church, Norfolk. © Anne Marshall 2000-2018

Close

Close