The Riddles in Old English Runes

28 May 2021

For this blog Lorna has been looking at three different objects with Old English Runes and their interpretations.

Introduction

Runic characters were used in early medieval Britain before the spread of Christianity introduced the Latin alphabet. These runic alphabets, found in Germanic and Scandinavian writing systems, were eventually replaced by the Latin alphabet, which evolved into the modern English alphabet we know today.

Like the modern alphabet, named for the first two letters of the Greek alphabet alpha and beta, these runic alphabets are known as futhark or fuþark, derived from their first six letters (Page 1999:200)

ᚠ (feoh), ᚢ (ur), ᚦ (þ[th]orn), ᚩ (os), ᚱ (rad), ᚳ (cen)

The Early Medieval variant used with Old English is called futhorc or fuþorc, due to the way Old English is pronounced.

There are about 30 known Old English runes, deriving from a number of different manuscripts and objects. The runes can indicate single letters or sounds, or represent full words, and many have multiple meanings. For example, the first rune in the Old English rune sequence is ᚠ (F) or feoh, which in Old English translates to “wealth” or “cattle”. Another example is ᛗ (m) or mann, which in Old English translates to “man”.

Runes can be used together to create personal names, usually found on coins or personal objects (Symons 2016:8). Personal names and some pagan gods also have their own runes, but these are mostly contested – such as the rune ᛏ (T) or Tiw, who is possibly a god similar to Mars. Although Old English runes appear in all the dialects of Old English, some runes are only found in certain dialects.

In this blog post we will explore three different objects that Old English runes appear on and look at the ways the runes are used, the translations, and how this has changed the interpretation of the object.

Objects with Runes

Objects with Old English runes on them are very rare. Fewer than 200 items have been found with recognisable runes on them and these objects have been dated from the fourth century AD to the eleventh century AD. However, they show us a varied use of inscriptions on objects ranging from religious items to personal items.

Seax of Beagnoth

Found near the Thames in 1857 the Seax of Beagnoth is a long knife dating to the 10th century AD (Findell 2014:37). It is almost unique because of the runic inscription found along its long edge. This object is so named as “seax” is the Old English word for knife and “Beagnoth” is a personal name found in runes on the blade edge - ᛒ (beorc, B), ᛠ (ear or ea), ᚷ (gyfu, G), ᚾ (nyd, N), ᚩ (os, O) and ᚹ (þ (th)orn, TH). When split into Old English “Beagnoth” becomes bēag “ring or crown” and nōþ meaning "boldness".

The Seax of Beagnoth. (c) The Trustees of the British Museum

On the opposite side to the personal name there are 28 runes spelling out the futhorc alphabet (British Museum). The runes inscribed on the blade do not include any of the runes found in Northumbrian dialect of Old English and scholars have speculated that it was made in Kent (Elliot 1980:79).

Kingmoor Ring

Possibly the inspiration for the all-powerful inscribed ring in Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, housed in the British Museum and having a diameter of only 27mm, the Kingmoor Ring is solid gold and dates to the 9th century AD (British Museum).

The Kingmoor Ring. (c) The Trustees of the British Museum

The ring has 30 runes around its gold surface and the last word is actually written inside the ring. The rune sequence runs like this ᛭ᚨᚱᛦᚱᛁᚢᚠᛚᛏᛦᚱᛁᚢᚱᛁᚦᚩᚾᚷᛚᚨᚴᛏᚨᛈᚩᚾ / ᛏᚨᚿ, which in Old English translates to ærkriufltkriuriþonglæstæpon/tol. This string of Old English cannot be translated directly, however, translators have taken the first few letters to be the Old English word “ærcrio.” This strange word appears in Bald's Leechbook (i.vii, fol. 20v) and is thought to be a magic word used as the beginning of a charm (Page 1998:291).

The Kingmoor Ring has, therefore, been suggested to actually be a magical amulet used as part of a charm (Meroney 1945). In the Leechbook the word “ærcrio” appears before a passage describing how to stop bleeding. If this is the right interpretation the rest of the rune sequence could be charm against bleeding. In the Leechbook the description looks like this:

“æȝryn. thon. struth. Fola arȝrenn. tart. struth. on. Tria enn. piath. hathu. morfana. on hæl +ara. carn. leou. ȝroth. weorn .lll.

Translation: “ærcrio they say, to stop blood, poke into the ear with a whole ear of barley, in such a way that he [the patient] be unaware of it...” (Cockayne 1865).

The Ruthwell Cross

Thought to be dated from c. AD730-760 the Ruthwell Cross is an example of insular art (Karkov 2011; Karkov 2020) found in the village of Ruthwell, which is now in Scotland, but during the early medieval period would have been in the kingdom of Northumbria. Contemporary with Bede and demonstrating an art form commonly associated with the Celtic Christian tradition, rather than that of the church dictated from Rome, it is a large stone crucifix with narrow sides with both images and more remarkably runic inscriptions of Old English text (Karkov 2020; Page 1999).

The Cross has four sides. The broad sides have scenes from the bible carved into them including scenes and characters such as John the Baptist, Jesus with two rats at his feet, Peter and Paul, the healing of the blind man and Mary talking to Elizabeth. On the narrow sides a vine scroll, representing the tree of life, is bordered with runic script in Northumbrian Old English. For a detailed description of the runes please see Howlett (2008).

The runic script looks like this: ᛣᚱᛁᛋᛏ ᚹᚫᛋ ᚩᚾ ᚱᚩᛞᛁ ᚻᚹᛖᚦᚱᚨ / ᚦᛖᚱ ᚠᚢᛋᚨ ᚠᛠᚱᚱᚪᚾ ᛣᚹᚩᛗᚢ / ᚨᚦᚦᛁᛚᚨ ᛏᛁᛚ ᚪᚾᚢᛗ / ᛁᚳ ᚦᚨᛏ ᚪᛚ ᛒᛁᚻ

This translates to line 56 of an Old English poem, The Dream of the Rood.

“Krist wæs on rodi. Hweþræ þer fusæ fearran kwomu æþþilæ til anum ic þæt al bih[eald].”

Translation: "Christ was on the cross. And there hastening from far came they to the noble prince. I beheld all that.” (Hamer 2015)

The poem can be found written in the Latin Alphabet in the Vercelli Book, and its inclusion on the Ruthwell Cross is significant as it shows a move away from the formulaic inscription of just writing the futhorc. The use of runes on the Ruthwell Cross indicates this as it is seen as a conversion tool mixing the mediums of Christianity and symbols seen as possibly pagan together.

Conclusion

With so few examples of Old English Runes especially found on objects any examples can show important details into the use of this language form. However, with the advent of Christianity across Europe the use of Germanic runes fell out of fashion. This was probably linked to the pagan roots associated with the symbols and ultimately the objects they appear on. Old English runes do however give a significant glimpse of how writing was used to convey personal names and ideas.

References

British Museum, Seax of Beagnoth. [Accessed 04/05/2021].

British Museum, Kingmoor Ring. [Accessed 04/05/2021].

Cockayne T O, 1865. Leechdoms, Wortcunning and Starcraft of Early England. Vol. II., London.

Elliott R, 1980. Runes: An Introduction. Manchester University Press.

Findell, M, 2014. Runes, British Museum Press.

Hamer 2015. A choice of Anglo-Saxon Verse.

Howlett D, 2008. A Corrected Form of the Reconstructed Ruthwell Crucifixion Poem. Studia neophilologica, 80(2), pp.255–257.

Karkov C, 2011. The Art of Anglo-Saxon England, Woodbridge: Boydell Press 137–38.

Karkov, C, 2020. The Divisions of the Ruthwell Cross. In The Wisdom of Exeter. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 131–156.

Meroney, H, 1945. Irish in the Old English Charms, Speculum 20, 172-82.

Page, R, 1998. Two Runic Notes. Anglo-Saxon England 27. P289-294.

Page, R, 1999. An Introduction to English Runes. The Boydell Press: Woodbridge.

Symons V, 2016. Runes and Roman letters in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts. De Gruyter. Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde - Ergänzungsbände 99.

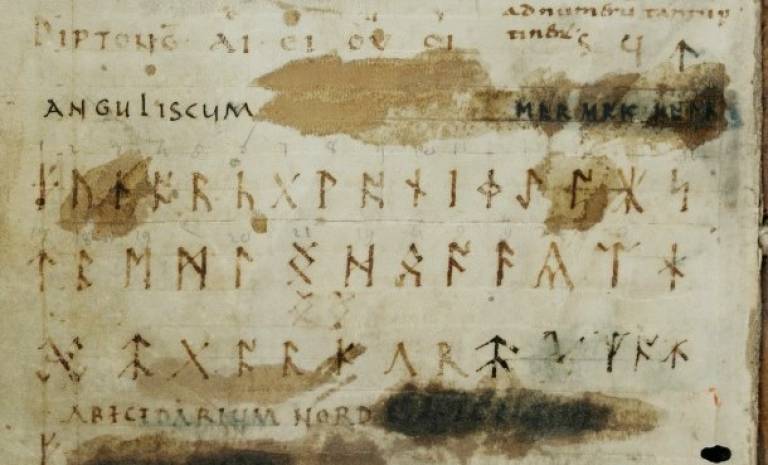

Cover image is the early medieval futhorc found in the Codex Sangallensis 878, p. 321. (c) St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 878, p. 321 – Vademecum of Walahfrid Strabo http://www.e-codices.ch/en/csg/0878/321

Close

Close