Encouraging student engagement with blended and online learning

Approaches and specific strategies to help encourage and maintain students' engagement with blended or hybrid learning.

13 October 2021

This toolkit focusses on approaches and specific strategies to help engage students and then maintain that engagement.

Success and engagement go hand in hand, leading teachers and lecturers to ask: What can I do to increase and sustain engagement? We attempt to answer this here but with a particular focus on blended and online modes of teaching.

The toolkit starts by setting out a definition and some core principles before offering some broad guidance through the lens of a simple and logical engagement framework. The final section separates engagement techniques appropriate for asynchronous content and activity development versus live, online sessions.

There is no point in teaching if nobody is learning! We can check learning at different stages but designing teaching approaches that centre on active engagement are most effective at ensuring learning is taking place.

Although blended and online learning offers all sorts of potential ways to add depth and dimension to student learning, they can also create additional barriers. This toolkit offers a launch point for all lecturing and teaching staff who want enhance learning and increase success rates by encouraging student engagement in online and blended modalities.

What we mean by 'engagement'

Despite its many varied meanings, ‘engagement’ in the context of teaching and learning can be broadly defined as a set of positive student behaviours. These include attention to and completion of work, visibility and active involvement in that work, and similar involvement in their interactions with peers, the teaching team and the wider university community.

Whilst engagement does not mean that students are learning per se, and indeed there is evidence to show that students tend to engage in learning activities that do not challenge them too deeply (Nuthall, 2007), higher levels of engagement do correlate to increased success.

Engagement will vary from programme to programme, and according to each individual’s needs and (to an extent) preferences. ‘Motivation’ can be seen as one of the pre-requisites to deep engagement but the two words are not synonymous. UCL’s connected curriculum framework is about engaging students through the various connections they should be making as they study. It makes a good starting point because it reminds us that engagement is much more than what happens in classrooms or in learning spaces online.

Key engagement principles

It is important to consider the core principles in each of the modes of engagement set out below, but you should also select from the ideas and activities according to your disciplinary area and the nature of the programme (especially its modality and the cohorts); use local knowledge to select what is likely to work best, or experiment with a range of approaches based on the principles and ideas here.

A student's individual level of engagement will naturally vary but the following factors will have an impact:

- The degree to which active and interactive opportunities exist

- Prudent/ limited use of didactic approaches

- Supportive, empathetic and approachable academic team

- Frequent developmental feedback

- The impact of the wider community; opportunities to form friendship groups and participant in other non programme-related activities (see Almarghani and Mijatovic, 2017, for a deeper exploration of these points and for a consideration of how technology can aid or impede a push against student passivity).

Aside from the last bullet point, academic staff have a degree of agency (to an extent limited by their role) on these factors and can work towards ensuring their teaching acknowledges these ‘needs’.

In addition, providing opportunities for students to participate in wider academic work of the institution as well as curricula and research level partnership activity on programmes and across faculties (HEA, 2015). See, for example, student teaching and quality reviewers initiatives at UCL and the range of staff/ student partnerships that make up the ChangeMakers scheme .

Modes of engagement

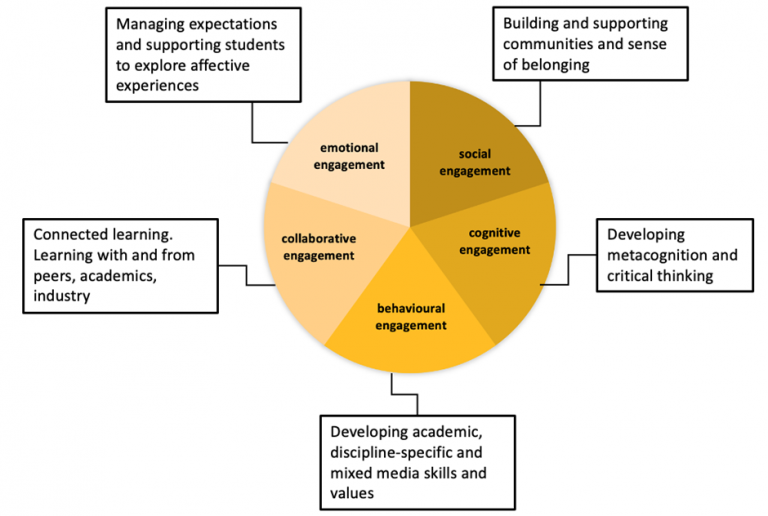

Before we start to develop strategies to improve engagement, it makes sense to consider our practice through the lens of an analytical framework, such as the simple one proposed by Redmond et al. (2018).

Online and blended engagement framework with definitions (adapted from Redmond et al., 2018)

Broadly speaking, the role of the educator is to foster an environment where each of these levels of engagement can flourish. Measuring such engagement across the modes is an impossible endeavour in a quantifiable sense but indicators of engagement / absence of engagement might be behaviours such as: working with others, actively seeking or providing peer feedback, making interpersonal connections in different media, responding / acting on feedback, showing enthusiasm, making connections or focused working. Thinking about the kinds of behaviours that signal engagement can help tutors determine earlier whether interventions might be needed.

Engagement approaches in online and blended teaching

Across the five areas of engagement, there are various strategies that stand out as broadly effective, notably modelling good practice, clarifying expectations and sharing agency. These are strategies that need to be embedded in practice so that they become habitual, as developing good engagement is a shared endeavour that takes time to become the norm.

In addition, there are various approaches that have proven effective in each of the five areas of engagement.

Here are our top tips:

- Social engagement

In live sessions: Allow time for socialising, chatting and asking / answering low stakes questions (may or may not be related to the session topic).

Encourage students to join, create and use social spaces. These can be virtual or physical and should be student-led though can be nudged by academic staff (especially in year 1).

Decide whether and how you will use discussion forums or equivalent asynchronous communications channels. Moodle forums or Microsoft Teams channels can be used for discussing ideas, peer work and review, asking questions or simply socialising- it’s important that the channels are consistent across modules and that there are not multiple alternatives.

Encourage active participation but expect slow starts. Use gentle prompts and value passive participation (sometimes known as ‘lurking’) which is a valid and important degree of engagement.

However: never push too hard, insist on certain behaviours (e.g. cameras on) or incentivise ‘compliance’ behaviours: this is likely to lead to the opposite effect in the long term of increased disengagement, especially amongst students who are experiencing heightened anxiety and / or neurodivergence as well as those students from different culture contexts.

- Cognitive engagement

Tell students why you (or they) are doing a certain activity.

Ask students to speculate on the underpinning purposes of a design of an assessment or the organisation of groups.

Allow processing time so chunk content and state with clarity the purpose of the content, how it should be approached and how the information will be used.

Vary activities, drawing on a range of (relevant) activities such as discussion, application, investigation (see ABC learning design ideas for more inspiration)

Use collaborative documents to co-create a solution to a problem or write a lab report.

- Behavioural engagement

Set expectations for presentation and format of work, discuss these pre and post early submissions and follow up in feedback.

Provide opportunities in office hours to discuss academic skills; make it clear that expectations vary in pre-university contexts, especially in different countries so there are no stupid questions.

Model and encourage subject appropriate (and, if relevant, employment) behaviours.

Recognise that each student will have skills and gaps in the ways they approach tasks. The classic misapprehension is that all students are digitally adept. Offer opportunity to walk-through advisable approaches and processes.

- Collaborative engagement

Consider, discuss and share the extent to which collaboration is a necessary skill in the disciplinary area per se and in career routes.

Rationalise collaborative work; pre-empt complaints about group work through discussion.

Assume some students will need what others might consider to be ‘basic’ guidance on how to use certain tools or approach certain tasks. If you suggest someone takes the role of ‘note-taker’ for example, have you discussed purpose, format, sharing, detail, formality?

Model use of (or at least recommend/ discuss) collaboration tools such as MS Teams or shared presentations or documents in Office 365 ahead of setting collaborative tasks.

Encourage students to set their own criteria for ‘success’ in collaborative activities and to evaluate themselves (and others) against their own criteria.

Flag staff-student partnership projects and opportunities like ChangeMakers.

Use the Connected Curriculum framework to explicitly discuss depth and breadth of engagement (perhaps in tutorials, office hours or in relation to research-based work, dissertations or placement activity).

- Emotional engagement

If you sense anxiety or confusion about something: Ask: how are you feeling about this project/ topic/ assessment? Those willing to share anxieties are likely to re-assure those that were feeling they were the only ones.

Use narratives and examples (possibly from own experience- your choice) to re-assure, pre-empt anticipated anxieties and to illustrate principles such as seeing value in all learning (such as a failed experiment or completely misinterpreting a task).

Enjoyment signifies and fosters engagement: what scope is there to inject energy or fun aspects into the studies?

Explore and discuss preferences with students- help them to embrace two key concepts: 1. Everyone is different- some may love silent absorption of lengthy lecture content; others may crave the chance to talk over everything and 2. Sometimes what we prefer is not the best way to tackle it!

Never apologise for work that is to follow as ‘boring’ or ‘necessary evil’ or ‘you’ll hate it but…’ this becomes a self-fulfilling prophesy and decreases engagement.

Digital options and tools

For asynchronous learning

It is an unusual course that has no element of ‘blended’. What varies is the degree, depth and sophistication of that blend. When designing the blend (especially in situations where a great deal of the content will be made available asynchronously) thought and care needs to be put into:

- The desired outcomes- knowledge, skills, collaboration, criticality, production and so on.

- The media used - including the range and quality required.

- The tools to be used - digital capabilities and access to essential technology is a consideration for both the academic team and students.

- Techniques for optimising engagement.

The UCL connected learning baseline is designed to support all these components and, as the name suggests, is the starting point. Key principles for optimising engagement include:

Get the students to the materials as efficiently as possible by minimising places where it is stored. Moodle is typically the portal to content and activities and channelling everything through Moodle using links, embedding and a consistent layout all reduce frustration, add clarity and can foster engagement.

Ensure you blend the types of learning activities you ask your students to engage with, so that they not only have an opportunity to ‘acquire’ new knowledge, but also to practice with it, discuss and collaborate with peers and produce novel content themselves. Laurillard’s six learning types (Laurillard, 2013) can help you identify an effective pattern, especially through use of the UCL Learning Designer tool.

Signpost everything with clarity and consistency in terms of: where to go; precisely what to do when they get there; what do with it after; how long it will take; and how crucial and/ or timebound it is

Content does not have to be in the form of video but if you do record video:

- Chunk the information (see this case study from Dr Danielle D’Lima)

- Voiced over slides alone are the least engaging video type

- Try to connect through the lens on a human level and with enthusiasm (fast pace is ok)

- High production quality is not essential but good audio is (use a microphone where possible). (Brame, 2016; Guo et al., 2014)

Consider creating spaces for collaborative and/ or individual written or record comments, discussion, outputs and evidence of learning. Blogs, discussion forums and MS Teams channels are all possible depending on context and needs. Most importantly you need to be clear about how optional these channels are. If assessed, then they lose the creative, innovative, whimsical potential that open and optional spaces often become. Be prepared in those instances to need to nudge, nurture and grow the spaces and accept that ‘lurking’ is a legitimate engagement (for more on this see Gilly Salmon’s 5 stage model).

ePortfolios are useful tools for student engagement provided they are used to give continuous feedback. Mahara is the institutional one but others exist through third party vendors (at a cost) e.g.Pathbrite, PebblePad) and Reflect is also used as a portfolio at UCL.

Open badges can be used for recognition and reward that is separate from the ‘ultimate’ reward of the degree. They can be endorsed by organisations and created using tools such as Open Badge Factory. Open Badges are easily displayed online via a range of options. Open Badge Passport is one option or they can be displayed via any web-based platform like LinkedIn or personal blogs.

Recognise that multiple ways of accessing information and ensuring clarity and consistency in design and language use are part of wider Universal Design for Learning Principles that benefit all students including those from typically marginalised groups.

Accessibility: It goes without saying that if a resource is inaccessible to someone with learning differences or disabilities they cannot engage. When designing resources it is worth referring to guidance both generally and specifically from the digital accessibility hub.

For live, online sessions

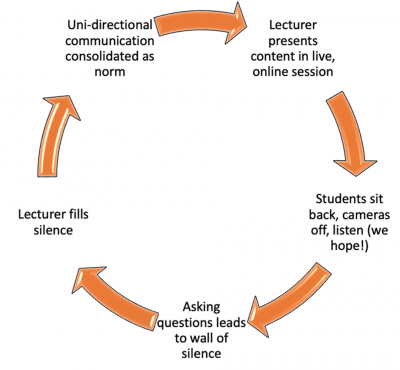

Whether you are using Zoom, Teams or another tool for live sessions online a key principle is to not see this as ‘delivery’ time.

Cycle of disconnection in live online sessions

Actively plan questions, or make observations or offer something unrelated or tangential to the topic to stimulate interest.

If you have set a pre-session activity, it’s a chance to display input and give early arrivals something to ponder, compare to their own responses or to quickly do (because they ‘forgot’!).

Setting expectations early on is important to establish a ‘norm’, especially regarding sensitive issues like cameras on/off. Whilst you should never insist on cameras on, as you can never know individual students' contexts, nonetheless research suggests that most students leave their cameras off only because they are concerned about their own appearance, or because they are in a shared space which others are also using (Castelli & Sarvary, 2021). The norm becomes cameras off, and this then persists.

Ideally, the session will be built around discussion, application or practice and will build on the resources and activities you have used to frame and the live event. Tools that you can use to support this include:

Your UCL Mentimeter account which is a place students can go to contribute thoughts, answer questions or provide insights. It works well for both asynchronous and synchronous interactions and, indeed, bridging the two. For example, you might choose to send a Mentimeter link ahead of a session, then close the voting just before the session then display the results and use that as a prompt for the in-session discussion. Alternatively (though harder to manage for both lecturer and student) is to run a live poll in-session as a way of engaging a wider number of students than those confident enough to turn on mics and cameras at the start.

Teams, Zoom and Collaborate all offer simple in-app polling tools as an alternative or, even simpler, pose a question and ask all students to drop a yes/ no/ don’t know/ ambivalent type response into the chat.

All these tools also offer breakout spaces and but, as with effective group work in a face to face setting, what they will do needs planning and the instructions need to be clear. This article offers detailed, practical guidance on using breakout spaces.

As part of a breakout activity, you could use a Jamboard collaborative space or equivalent to give a visible focal point to discussions and provide an shareable output of the discussions.

Alternatively, use Moodle Hot Questions in live sessions as described by Dr Rebecca Yerwoth to encourage anonymous contributions that can be discussed and voted on by students.

Those Faculties with access to social annotation software (Talis Elevate and Hypothes.is) can use these to create engagement with texts. By asking questions within images, videos and texts discussions can take place either in a seminar or outside face to face teaching time. Those who have used it have reported a higher engagement with readings across the term.

Although there are two sections above, to sustain engagement it is important to make visible the connections between what happens live (whether it is in a lab, classroom or online) and what happens asynchronously. Building those bridges by making those connections overt is essential.

Further help

For online and blended learning support, contact your Faculty Learning Technology Lead.

If you would like to create or redesign your online course, or receive training about online courses (including online centred ABC), contact a member of the Online Learning team.

For development of blended courses, including blended ABC training, contact a member of the Digital Education Advisory team.

To discuss any of the teaching and learning ideas and issues here please contact your Arena faculty liaison.

For more on Mentimeter, visit the Mentimeter resource centre and see our case study on How Mentimeter can support asynchronous engagement.

- Click to view references and further reading

Tools and ideas for engagement:

Encouraging engagement in breakout room activities

Equity Unbound resource collection for online community building.

Strategies to Encourage Students to Turn Their Cameras On

Theoretical and policy landscape:

Almarghani, E. M., & Mijatovic, I. (2017). Factors affecting student engagement in HEIs-it is all about good teaching. Teaching in higher education, 22(8), 940-956.

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Viewed 8 March 2021 [http://udlguidelines.cast.org]

Castelli, F. R. & Sarvary, M. A. (2021). Why students do not turn on their video cameras during online classes and an equitable and inclusive plan to encourage them to do so. Ecol Evol., 11, 3565-3576. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7123

HEA (2015) Framework for student engagement through partnership. Available: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/sites/default/files/downloads/student-enagagement-through-partnership-new.pdf

Nuthall G (2007). The Hidden Lives of Learners. Wellington, NZ: NZCER Press.

Redmond, P., Abawi, L. A., Brown, A., Henderson, R., & Heffernan, A. (2018). An online engagement framework for higher education. Online learning, 22(1), 183-204.

Video and engagement:

Brame, C. J. (2016). Effective educational videos: Principles and guidelines for maximizing student learning from video content. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 15(4), es6.

Guo, P. J., Kim, J., & Rubin, R. (2014, March). How video production affects student engagement: An empirical study of MOOC videos. In Proceedings of the first ACM conference on Learning@ scale conference (pp. 41-50).

Collaboration tools:

Talis Elevate and hypothes.is (social annotation for images and texts) used in History, Archaeology, Anthropology and Economics

Learning types and active learning online:

https://www.futurelearn.com/info/courses/blended-and-online-learning-design/0/steps/191671 (Learning Types)

Active learning online from Alex Mihai

Active learning at a distance from Derek Bruff

25 Strategies to engage students in your next Zoom session

Khan, A., Egbue, O., Palkie, B., & Madden, J. (2017). Active learning: Engaging students to maximize learning in an online course. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 15(2), pp107-115.

Laurillard, D. (2013). Teaching as a design science: Building pedagogical patterns for learning and technology. Routledge: Chicago.

Close

Close