The following text has been adapted from: https://www.repurposingmedicines.org.uk/ (LifeArc online tool kit for Repurposing Medicines)

- Where to start: identification of a candidate molecule and planning of the Target Product Profile (TPP)

Target identification

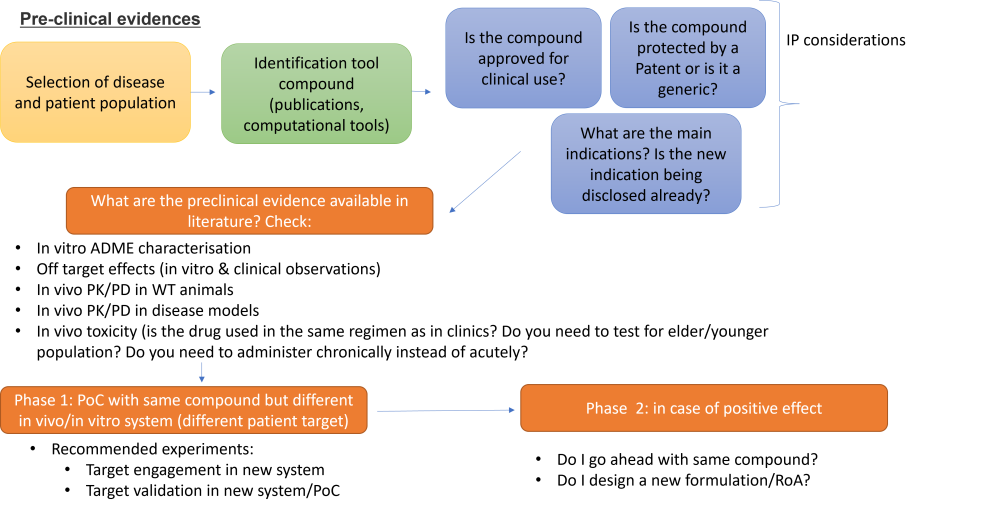

A drug repurposing strategy, as any other development pipeline for therapeutics, consists of three main steps:

- identification of a candidate molecule for a given indication (hypothesis generation);

- mechanistic assessment of the drug effect in preclinical models;

- evaluation of efficacy in phase II clinical trials (assuming there is sufficient safety data from phase I studies undertaken as part of the original indication) (Pushpakom, et al. 2018).The identification of the right drug for a given indication can be achieved by either computational or experimental approaches, or most likely, by using both. Computational models include signature matching, computational molecular docking, genome-wide association studies, retrospective clinical analysis, and more. Experimental studies include binding assays to identify target interactions and phenotypic screening to name some.

The Target Product Profile

The stage at which a repurposing project enters the development path varies from project to project, and in most cases the lead candidate is already identified. Before committing to a specific molecule, it is worth thinking about the Target Product Profile (TPP). The TPP is a list of critical elements that need to be addressed when developing a treatment, and identifying these early on is speeding up timelines, reducing risks and facilitates the commercial path.- Target patient population (or sub population - early engagement with a clinical team can help identifying the best population and also evaluating the study feasibility). Associated with this point is the possibility to have a Timely Diagnosis: would existing diagnosis methods and timings allow you to deliver the planned intervention?

- Efficacy/benefits to the target patient population when compared to other options or standard of care (has the proposed therapy fewer side effects? is it administered less invasively? ...)

- Pharmacokinetics (is the drug targeting the right organ?)

- Formulation (good to know historical data, this can - or sometimes will need - to be changed to address the effect for the desired time frame. -> Is there a need to reformulate? This could be a winning strategy to ensure novelty for intellectual property (IP) matters. Visit IP considerations and partnership for further information). If reformulation is done, the pharmacokinetics (PK) need to be re-addressed.

- Potential drug-drug interactions, co-morbidities and other safety risks in the target patient population

- Route of administration

- Dosing (What dosing is appropriate for the new indication? Does it require a different dosing strategy to the original indication? Note: Dosing rationale is often under-studied and needs very careful consideration early on to avoid selecting the wrong dose) -> Do you need to carry out a dose escalation study?

- Are any specialist equipment or facilities needed to administer the therapy to patients?

To ask for help designing the TPP, UCL has an internal support group, the Repurposing | UCL Therapeutic Innovation Networks - UCL – University College London. The Repurposing TIN has 2 experts (Prof Oscar della Pasqua and Dr Stephen Hobbiger) that will help you outline the right questions and needs for a grant application/ industry collaboration. Please contact Dr Asha Recino and Dr Eleonora Lugara' to ask more about this resource.

Most of these aspects need to be considered when drafting the wording for the new repurposed indication in the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). The SmPC is the formal, licensed clinical particulars of the product, approved by MHRA and therefore instructs prescribers how to use licensed medicines. It is a pivotal document. Examples of target product profiles can be found on the websites of the World Health Organisation and the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative.

Another important aspect is the early engagement with patients or patients advocacy group. Contact your disease-dedicated charity or the Association of Medical Research Charities (AMRC) may be able to help you find and contact the appropriate communities.The rare disease charity for patient groups, Beacon (formerly Findacure) may also be able to help.

- What to consider: freedom to operate, intellectual property and partnership

Having a clear path to generate intellectual property (IP) will increase the chance of getting funded and facilitate partnership (needed to a later stage for clinical studies and GMP - good manufacturing practice - production of the drug). Having said that, not having any IP is not an insurmountable impediment to progress the re-development (see below case 3), but what is needed is checking having clear FREEDOM TO OPERATE (also called 'infringement search').

What Is Freedom to Operate? Freedom to operate (FTO) is the ability to develop, make, and market products without legal liabilities to "third parties" (e.g., other patent holders) (www.morganlewis.com). You are free to operate when 1) a company agrees to license you the patent and 2) if the patent has already come to an end. Contact UCLB to help you clearing the FTO.

IP & Partnership, read about the most common situations you might find yourself in:

- Case 1: the drug you want to repurpose is still covered by a patent and the originator company is interested in collaborating -> Please check the patent landscape, use the website The Lens - Free & Open Patent and Scholarly Search (or google patent). In this case contact the Tech Transfer office (UCLB) and/or ask the BIG (TRO), to put you in contact with the originator company (likely to be the patent owner) to discuss shared development or licensing opportunity. To check who is the Marketing Authorisation holder use the MHRA resource MHRA Products | Search results or the Electronic Medicines Compendium (EMC).

* Make sure to have an NDA or CDA (non disclosure agreement or confidentiality disclosure agreement) before disclosing patentable information. Progressing the project in partnership with the originator company is the easiest way as they may have data and know-how related to the product that could be relevant to the new use. They may also provide material for the trial (very expensive at GMP grade) and may lead the process of obtaining Marketing Authorisation licensing for the new indication.

- Case 2: the drug you want to repurpose is still covered by a patent and the originator company is NOT interested in collaborating.

1) Ask UCLB about 'freedom to operate'. There might be the option to pay for a license and carry on the R&D work.

2) try to contact a generic manufacturer, or more than one – they may be able to advise on exclusivity and patent information too (please inform UCLB first). They may also be able to help with drug supply and possibly with Market Authorisation. The British Generics Manufacturers Association (BGMA) can help with introductions. Visit Resources - BGMA.

* The BGMA currently has 33 member companies. BGMA are willing to be very involved at the earlier stages of development and part of their remit is to ensure that there is a neutral voice in discussions such as those around pricing. BGMA have a wealth of experience in the repurposing field and are very happy to engage. They can broker relationships with their member companies as appropriate. BGMA can be contacted via email at info@britishgenerics.co.uk

- Case 3: the drug you want to repurpose is NOT covered anymore by a patent (off-patent) and there are generics on the market.

1) Check very well the indication, formulation and dose that has been already patented and if any variations have been publicly disclosed.

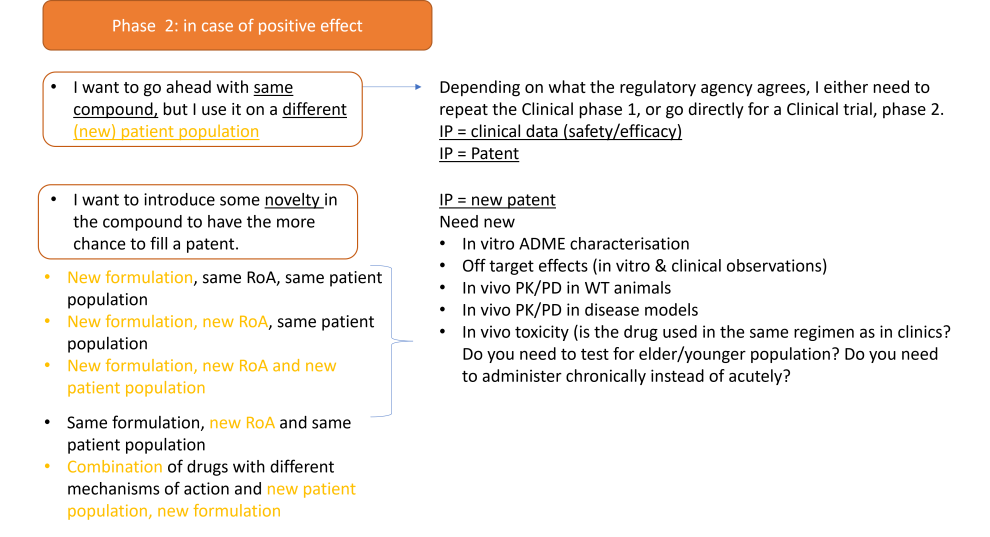

2) Consider whether you can re-patent the medicine with a ‘new’ feature. Novelty can come from:

o A new indication (The choice of a different patient population)

o A new active or derived-active ingredient with a similar therapeutic effect

o A new chemical formulation

o A new route of administration

o Combinations of at least two drugs previously used as separate drug products

o Obtaining exclusive marketing approval in new geographic regions

All these options will need the generation of new preclinical (in vitro, in vivo, chemistry, toxicity) data; therefore need for funding. See the section dedicated to funding to see what your options are. See the section dedicated to recommended pre-clinical studies to see what is the advised strategy.

* for UCL researchers: PROTAC & AUTAC Opportunity for UCL researchers | UCL Therapeutic Innovation Networks - UCL – University College London The Small Molecules TIN has purchased a stock of molecules suitable for modification into functional PROTACs, and a stock of AUTAC4, which are available to UCL researchers for free. PROTACs/AUTACs are a new technology that chemically knocks-out a protein of interest by directing it to the Proteasome or to Autophagy. They are particularly useful for cell biology and in-vivo studies.

3) if there is no possibility to patent any new aspect of the drug, the generation of pre-clinical and new clinical/tox studies is probably still required. Therefore it is still recommended to review the publicly available knowledge so far and start with the generation of (in vitro, in vivo, chemistry and toxicity) proof-of-concept studies. The main difficulty associated with non-patentable repurposed drugs is finding suitable funding. The best strategies are:

o connect with disease charities or philanthropic funds and ask for seed/pre-clinical funding. If successful, these entities can go as far as funding the early phases of clinical trials.

o contact a generic manufacturer, or more than one if this is the case. They might help find solutions and funding new studies.

o search for internal (university, VC, tech transfer) pot of funding

o pitch your idea to pharmaceutical industries able to invest a pot of money in proof-of-concept studies. These data can be the starting point for a new project in which it is possible to develop A) a new chemical entity, B) change modality [from a drug to a virus/plasmid/ASOs/biologic] C) pinpoint a new therapeutic target

o off-label use (for medical professionals only) if there is a clear rationale. Make sure to follow up with the patients and write a clinical case to show the advantages and the possible side effects.

- Case 1: the drug you want to repurpose is still covered by a patent and the originator company is interested in collaborating -> Please check the patent landscape, use the website The Lens - Free & Open Patent and Scholarly Search (or google patent). In this case contact the Tech Transfer office (UCLB) and/or ask the BIG (TRO), to put you in contact with the originator company (likely to be the patent owner) to discuss shared development or licensing opportunity. To check who is the Marketing Authorisation holder use the MHRA resource MHRA Products | Search results or the Electronic Medicines Compendium (EMC).

- Funding

- UCL internal: TRO TIN repurposing call Funding Opportunities | UCL Therapeutic Innovation Networks - UCL – University College London

- Philanthropic funds, for example:

- The LifeArc Philanthropic Fund provides grants and funding to academic researchers working to advance new treatments and diagnostics for rare diseases.

- Non clinical R&D: MRC schemes

- MRC impact acceleration accounts (previously confidence in concept) – UKRI The aim of this programme is to speed up the transition from discovery research to translational development projects. It will do this by funding preliminary work to establish the viability of an approach and to rapidly de-risk projects across the whole translational pathway. This may include data gathering to support drug repurposing projects. Decision-making and administration are managed locally, usually through a university's Translational Research Office.

- MRC Experimental medicine – UKRI supports projects with the primary objective of investigating the causes, progression and treatment of human disease, with a clear path to clinical impact. Projects must involve an experimental intervention or challenge in humans, which has been designed to validate a mechanistic hypothesis based on a gap in understanding of human pathophysiology. This may include the use of drugs with established safety profiles in new settings or conditions (for example, repurposing drugs as tool compounds to probe disease mechanisms). Annual budget c. £10 million; two rounds per year.

- MRC Developmental Pathway Funding Scheme: The MRC's flagship translational scheme, supporting academically-led projects aiming to develop and test novel and repurposed therapeutics, medical devices, diagnostics and other interventions across all areas of unmet medical need. Repurposing projects can include pre-clinical or clinical studies up to and including phase IIa. Annual budget c.£30 million; three rounds per year.

- Mechanistic work in vitro or in animals, or development and validation of disease models, which may utilise repurposed compounds, would fit within the MRC Research Boards:

- Infections and immunity – UKRI

- Molecular and Cellular Medicine

- Neurosciences and Mental Health

- Population and Systems Medicine. - MRC/NIHR Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation: supports later phase (IIb and III) clinical trials aiming to test the efficacy of interventions, including repurposed drugs. This includes proof of clinical efficacy, size of effect, and long-term safety in a well-defined population. Where appropriate, the programme encourages hypothesis-testing mechanistic studies integrated within the main efficacy study. This scheme is available across the whole UK.

- NIHR schemes:

- NHS program:

- NHS England » Repurposing medicines in the NHS in England. The Medicines Repurposing Programme is a national multiagency initiative which identifies and progresses opportunities to use existing medicines in new ways, outside the current marketing authorisation. There is an open call for healthcare professionals, charities and companies to put forward candidate repurposing opportunities for consideration. Medicines prioritised to enter the programme receive a tailored package of support potentially including evidence generation, facilitating licence variation applications, and support for implementation. The programme supports repurposing projects, in England, that have already achieved evidence of safety and efficacy in the target patient population, usually as part of a phase 2 trial but not always. For eligibility and prioritisation criteria visit Medicines Repurposing Programme. The programme will carry out its own diligence re IP landscape/ treatment pathway etc when considering applications to the programme. The process for application is explained on the scheme website.

- Depending on the IP situation around the therapy that you are looking to repurpose, the patent holder or, if off patent, the originator company, may also invest in a repurposing programme.

- Pre-clinical evidences

The power of repurposing a drug is that at, some point in time and space, data were already generated to approve this compound for a (or more) specific indication. This does not mean that all the data needed for a new regulatory submission is already available, and most of the time new trials or pre-clinical studies are necessary. This often happens when the data from the preclinical or clinical studies for the original product are outdated and therefore do not meet actual regulatory requirements (Murteira et al., 2014).

Assuming this is not a screening exercise and the drug to repurpose in a selected patient population were already identified, the type of preclinical studies that need to be done will heavily depend on the type of 'novelty' proposed:

o Same compound (formulation, dose, RoA), but different patient population: it is highly likely that PoC studies in cell lines derived from patients and (if possible) rodent models with target engagement and phenotypic readout are required. Make sure that the in vivo model(s) are compatible for the targeted sex, age and disease stage. Make sure your target engagement is translatable in clinical practice for the stage of clinical trials (biomarkers). Check that the PK/PD is similar to those published in the chosen patient population.

o New formulation & new patient population (see below)

o A new route of administration, new patient population & same formulation (see below)

o Combinations of drugs with different mechanisms & new patient population

These last three options will likely require the capabilities of a medicinal chemist and to check that in vitro and/or vivo, the PK/PD characteristics are compatible with the therapeutic target. Markers for safety and efficacy will also be required (usually the therapeutic effect needs to be superior to the drug that is already used as of standard of care, if applicable).Sometimes it might be more convenient to ask a CRO (contract research organisation) to carry out the in vitro/in vivo experiments for a fee. Please read these guidelines carefully about how to choose a CRO and what legal agreements are usually required.

- Clinical evidences

Clinical trials are necessary to gain confidence in safety and efficacy of the treatment in the new indication. Usually a novel drug needs to be first tested in a group of healthy volunteers to make sure it is safe at a relevant dose before it is tested in patients. This is called a Phase I trial.

For a repurposed medicine this may not be necessary because the drug has probably been already tested in humans, though this might not be applicable if a new formulation has been developed. It is recommended to always seek expert advice by the local R&D (JRO), TRO or other regulatory office. The MRC Regulatory Support Centre (RSC) provides support and guidance on the legal and ethical requirements for research involving human participants, their tissues, or data.

If a trial in healthy volunteers is not needed then it is possible to progress straight to Phase II, where the repurposed medicine is tested in the new patient group. Information about a safe and effective dose, relevant to the target patient population, should be generated where necessary in addition to existing data.

Innovative trial designs, especially in the rare disease space, have been developed to maximise the amount of data generated from a single trial or group of participants. These include:

- Umbrella/platform trial for multiple interventions (multi-arms) in a single disease (example: Zilucoplan, Pridopidine, Verdiperstat, CNM-Au8) with a shared placebo.

- Basket trial for a single medicine in multiple diseases with a common endpoint and biomarker (example: Zogenix)

Other helpful links for trial design are:

The NIHR Clinical Trials Toolkit provides advice for the planning and conducting of trials in the UK. If your intended trial is in children, you may need a Paediatric Investigation Plan (PIP). Guidance can be found on government Procedures for UK Paediatric Investigation Plan (PIPs) webpage- Regulatory environment

US:

• The drug application for repurposed drugs is usually filed according to section 505(b)(2) of the regulatory path. Other two legislation are strictly linked:

• 505(b)(1): Traditional drug development via the 505(b)(1) pathway is typically used for novel drugs that have not previously been studied or approved. 505(b)(1) drug development requires the sponsor to conduct all studies needed to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of the drug.• 505(b)(2): The Hatch-Waxman Amendments of 1984 were designed to prevent the duplication of existing studies via the creation of the 505(b)(2) pathway. A 505(b)(2) program must demonstrate safety and efficacy to the same standards as a 505(b)(1) program. However, existing data from studies not conducted by or for the sponsor, and for which the sponsor does not have right of reference, may be used to meet some or all of the safety and efficacy requirements. This usually means a 505(b)(2) drug product can be developed with less risk, in shorter time, and at lower cost (if done well) than a 505(b)(1) product. The large variation in types and strategic efficiencies of 505(b)(2) development programs creates a large range of time/cost estimates, but all are well below estimates for a 505(b)(1) program.

• 505(j) ANDA: Abbreviated new drug, or generic, approval requires a Sponsor to demonstrate bioequivalence to an innovator drug in lieu of replicating efficacy and safety studies. Generics are delayed from gaining marketing approval until the patent and marketing exclusivity for the innovator product have expired, the patents have been successfully challenged, or the application holder of the innovator product agrees to waive the exclusivity for the generic applicant.(premierconsulting.com)

EUROPE:

• Directive 2001/83/EC (particularly articles 6, 8(3), 10(3) and 10(5)) provides the main legal basis for drug applications for repurposed drugs. The application process for repurposed drugs in Europe can be filed via three different routes: centralized, decentralized or national application (mutual recognition).

• The application should contain information on pharmaceutical (physicochemical, biological or microbiological) tests, non-clinical (toxicological and pharmacological) tests and clinical trials. Some of the data requirements can be met by bibliographic data. In addition, for article 10 (abridged) applications that refer to data of a reference medicinal product, data requirements may be reduced.

• Safety characterization may be supported by prior clinical experience (such as trial data or post-marketing data).

• All applications should be accompanied by a risk management plan.

• All applications under article 8(3) require a Paediatric Investigation Plan or waiver, to be agreed with the European Medicines Agency (EMA) before application.

• A new indication for an approved drug could be added using a variation application.

(Pushpakom et al., 2018)- After a clinical trial

The most usual path to patient access for a newly developed therapeutic in the UK would be via MHRA granting a marketing authorisation licence, and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), or the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) in Scotland, conducting a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) to recommend reimbursement by the NHS. This route may apply to a repurposed medicine that is under market exclusivity, but probably will not apply to repurposed generics and biosimilars.

If the HTA is successful, your medicine will be recommended for adoption by the NHS and this will result in it being available for prescription “on-label”.

While achieving marketing authorisation is the “gold standard” for a repurposed medicine, as it may provide more robust and equitable access for patients, this may not always be possible. It can be a lengthy (18 to 24 months), and costly, process if a completely new marketing authorisation is needed. Repurposing an existing generic medicine is quick, with a variation to the licence only taking about six months.

The alternative is to prescribe the repurposed medicine “off-label”, which means that it has not been granted a marketing authorisation for the new use.

For certain projects that can be included in the prioritised programme, the Medicines Repurposing Programme can provide a quick and free process for applying for licence variations for new uses of generic medicines. Visit Funding - Medicines Repurposing Programme for further information.

Close

Close