The origins of UCL in Bloomsbury parallel the development of UCL East

15 July 2019

Amy Smith, a historian in the Survey of London at the Bartlett School of Architecture, has discovered some interesting parallels between the origins of UCL in Bloomsbury and its current expansion into east London

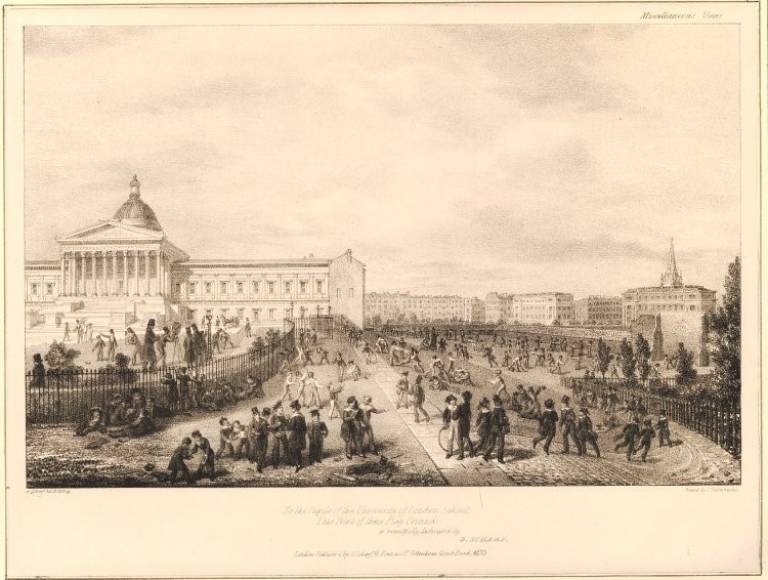

UCL traces its beginnings to a group of radical thinkers who wished to establish a secular, non-residential metropolitan university. In 1825, the Scottish poet and writer Thomas Campbell published an address in The Times to the lawyer, politician and educational reformer Henry Brougham, outlining the core elements of his idea for a London university. The institution was to be the first university in the capital and the only one of its kind in England. Now, the tradition in which UCL was founded in Bloomsbury in 1826 will grow and develop with UCL East, UCL’s largest expansion since it was founded in 1826.

The early years of the Bloomsbury campus contains several themes that coincide with the formation of UCL East. Parallels may be drawn with the aspirations of the university’s founders in their endeavour to bring innovation and accessibility to higher education. The new campus aims to connect teaching and research across eight faculties, with a focus on four main themes – experiments, arts, society and technology. This academic network will be working towards addressing significant questions relating to health, globalization, property, technology, urbanism and the environment.

Another similarity lies in the regeneration of Stratford, which was a centre for the capital’s industries in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The site of the new campus was part of a large sweep of marshland in the Lower Lea Valley, bisected by canals lined by workshops, factories and distilleries in the nineteenth century. While the character of Bloomsbury evolved in a gradual and incidental manner, regeneration is an important and deliberate component of UCL East. The location of the new campus in Stratford with other major cultural institutions (including the Victoria & Albert Museum, Sadler’s Wells and the London College of Fashion) is part of creating a legacy from the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

The idea that university buildings represent institutional identity or aspirations has gained currency in architectural writing. In Bloomsbury, the neoclassical portico of the Wilkins Building is widely interpreted as a proclamation of the secular values of the university’s founders. The promotion of the new campus in Stratford seems to respond to the coincidence of myth, idealism and aspiration in Bloomsbury – and it is natural for an offshoot of a historic institution to share in its heritage. The first phase of UCL East has been perceived as a new approach to developing a university campus for the twenty-first century, embedded in the local community and business. The buildings will provide space and facilities for academic units working on significant issues for today’s rapidly changing world, while participating in the regeneration of an urban area. In this sense, its aspirations and impact are not so far removed from UCL’s founders and the first campus in Bloomsbury, offering a story of continuity and parallels against a backdrop of innovation and change over two hundred years.

Amy Smith works as a historian on the Survey of London at the Bartlett School of Architecture. Amy has recently researched the Royal London Hospital and its estate for the Survey's current study of Whitechapel and is now working on a forthcoming volume on Oxford Street. Her doctoral research on the architectural history of UCL will contribute to a Survey of London monograph.

A full article on the links between the development of UCL in Bloomsbury and the new UCL East campus can be found by following this link.

Global Urbanism, in the Pool Street West building (Future Living Institute) of UCL East, will draw on our breadth of expertise on cities and the university’s history of radical urbanism, it will open up access to UCL’s public and oral history collections and expertise on London. Further information about the Future Living Institute can be found by following this link.

Close

Close