Amy Smith of the Survey of London has discovered some interesting parallels between the origins of UCL in Bloomsbury in the 1800s and UCL's current expansion to develop a campus in east London

Words by Amy Smith, who works as a historian on the Survey of London at the Bartlett School of Architecture. Amy has recently researched the Royal London Hospital and its estate for the Survey's current study of Whitechapel and is now working on a forthcoming volume on Oxford Street. Her doctoral research on the architectural history of UCL will contribute to a Survey of London monograph.

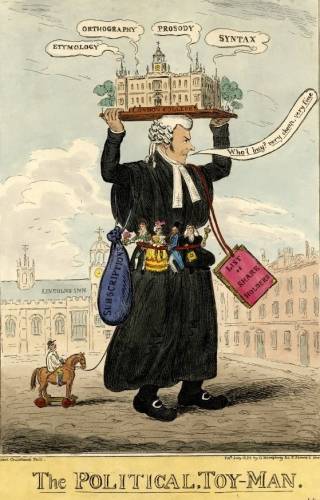

UCL traces its beginnings to a group of radical thinkers who wished to establish a secular, non-residential metropolitan university. In 1825, the Scottish poet and writer Thomas Campbell published an address in The Times to the lawyer, politician and educational reformer Henry Brougham, outlining the core elements of his idea for a London university. The institution was to be the first university in the capital and the only one of its kind in England. While Oxford and Cambridge had a tutorial system, residential colleges and religious tests which excluded all but Anglicans from obtaining a degree, the new university would offer a broad curriculum in a lecture-based system to students of all faiths. Brougham was soon at the helm of plans for the university, which was to be funded by shareholders and fee-paying students.

Figure 1 – Satirical cartoon depicting Brougham selling shares for the London university, July 1825 (Trustees of the British Museum, 1868,0808.8662)

A site comprising 7½ acres of undeveloped land was purchased at the north end of Gower Street, one of the last portions of ground not yet built on in a mostly residential district. This piece of ground was formerly intended for Carmarthen Square, destined for an ‘elegant and respectable class of buildings’, or so an advertisement for the sale of the site stated in 1824. In reality, it had fallen into neglect and resembled a swampy wasteland. The Tory newspaper John Bull fixated its opposition to the university on its choice of site. An invective launched on Christmas Day in 1825 reported the ‘large space of mud and nastiness’ that had been purchased by the ‘Joint-Stock Carmarthen Street University’. The nickname ‘Stinkomalee’ (which appeared in John Bull over the course of thirty-five years) stressed the boggy condition of the site, insinuating that the university rested on an uncertain footing. The establishment of the university in Gower Street contributed to the nineteenth-century evolution of Bloomsbury from a residential district to the intellectual quarter of London.

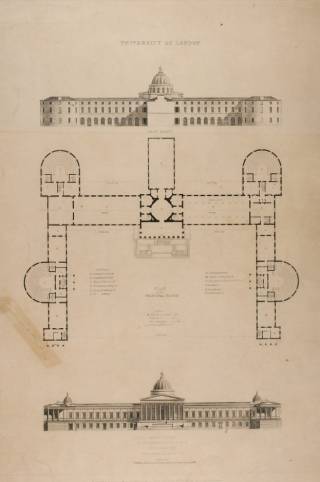

Despite this controversy, the Bloomsbury site was ideally positioned to serve the aims of the university, being in a central location and within reach of its target market – young men from the so-called ‘middling classes’ seeking an education close to their family homes or opportunities for training and apprenticeship. An architectural competition was organized to obtain designs for the university, and six architects were invited to compete. The university’s building committee requested ‘a building most perfectly adapted to all their objects’, with space for around twenty-nine lecture courses. The task of selecting the winning design navigated a long list of concerns, but the university was swayed by the projected cost of the proposals and selected the plan that promised to be the least expensive – a design for a neoclassical quadrangle submitted by William Wilkins, an experienced collegiate architect.

Figure 2 – Final design for the university quadrangle (UCL Digital Media)

Wilkins’s plan combined grandeur with practicality and the promise of affordability. A ten-columned portico, the only example of its kind in England, would open into a vestibule flanked by a great hall, a museum and a library. Wilkins proposed twenty-six lecturing halls and an extensive medical department, along with leisure spaces for students. His competition design was severely reduced after building tenders were unexpectedly high, and the university decided to proceed with constructing only the east wing initially. The foundation stone of the east wing was laid in April 1827, and the building opened to students in October 1828.

Figure 3 – The London university and the playground of its associated junior school, illustrated by George Scharf in 1833 (Trustees of the British Museum, 1880,113.4738)

The early years of the Bloomsbury campus contains several themes that coincide with the formation of UCL East. Parallels may be drawn with the aspirations of the university’s founders in their endeavour to bring innovation and accessibility to higher education. The new campus aims to connect teaching and research across eight faculties, with a focus on four main themes – experiments, arts, society and technology. This academic network will be working towards addressing significant questions relating to health, globalization, property, technology, urbanism and the environment.

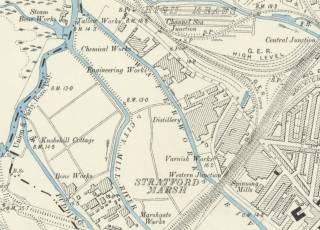

Figure 4 – Map of Stratford Marsh, 1894–6 (Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland)

Another similarity lies in the regeneration of Stratford, which was a centre for the capital’s industries in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The site of the new campus was part of a large sweep of marshland in the Lower Lea Valley, bisected by canals lined by workshops, factories and distilleries in the nineteenth century. While the character of Bloomsbury evolved in a gradual and incidental manner, regeneration is an important and deliberate component of UCL East. The location of the new campus in Stratford with other major cultural institutions (including the Victoria & Albert Museum, Sadler’s Wells and the London College of Fashion) is part of creating a legacy from the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Figure 5 – Masterplan for UCL East (LDA Design)

The procurement of plans for UCL East also followed a competitive process, and was the focus of lengthy and complicated consultations. The first step was the selection of a masterplan for the campus to provide a framework for its long-term development. In 2015, a team led by LDA Design was chosen to develop its scheme in collaboration with the London Legacy Development Corporation, the official planning body for the Olympic Park. The size of the campus was increased to 180,000m2, equating to around 40% of the size of the Bloomsbury site. The next step was to invite plans for the first phase of the masterplan, comprising two buildings at Pool Street and Marshgate. A shortlist of five teams for each building was announced in 2016. A team led by Stanton Williams was chosen for Marshgate 1, and a team led by Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands was selected for Pool Street West.

Figure 6 – Architects’ visualization showing Marshgate 1 and the Waterworks River (Stanton Williams)

Located to the south-east of the Olympic stadium, Marshgate 1 has been planned as the first main academic building in the new campus, containing a mixture of laboratories, studios, workshops and exhibition areas. The building has been designed to invite interaction with the public, with large expanses of glazing on the lower levels, a café and a foyer with a full-height atrium. Pool Street West will be positioned on the opposite bank of the Waterworks River, connected to the Marshgate site via a bridge. This mixed-use complex will be composed of two residential towers over an academic podium building, also designed to facilitate engagement with the local community with exhibition spaces and an auditorium.

Figure 7 – Architects’ visualization showing Pool Street West (LDS)

The idea that university buildings represent institutional identity or aspirations has gained currency in architectural writing. In Bloomsbury, the neoclassical portico of the Wilkins Building is widely interpreted as a proclamation of the secular values of the university’s founders. The university’s nickname, ‘the godless college of Gower Street’, is probably as familiar today as ‘Stinkomalee’ in the nineteenth century. The promotion of the new campus in Stratford seems to respond to the coincidence of myth, idealism and aspiration in Bloomsbury – and it is natural for an offshoot of a historic institution to share in its heritage. The first phase of UCL East has been perceived as a new approach to developing a university campus for the twenty-first century, embedded in the local community and business. The buildings will provide space and facilities for academic units working on significant issues for today’s rapidly changing world, while participating in the regeneration of an urban area. In this sense, its aspirations and impact are not so far removed from UCL’s founders and the first campus in Bloomsbury, offering a story of continuity and parallels against a backdrop of innovation and change over two hundred years.

Sources

Rosemary Ashton, Victorian Bloomsbury (New Haven and London, 2012)

H. Hale Bellot, University College London, 1826–1926 (London, 1929)

English Heritage, ‘London’s Lea Valley: The Olympic Park story’ (English Heritage, 2012)

Negley Harte, John North and Georgina Brewis, The World of UCL (London, 2018)

UCL Special Collections, Archives and Records

Close

Close