Applying behaviour change science to prevent sexual misconduct - Blog post

25 November 2021

UCL Centre for Behaviour Change and UCL Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) launch a report detailing the systemic influences on staff-to-student sexual misconduct within UCL using Behavioural Systems Mapping

Applying behaviour change science to prevent sexual misconduct

In Part Two of the blog series on the application of behaviour change science to organisational development, CBC Deputy Director Dr Paul Chadwick, Kelsey Paske (Independent Consultant and former Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Manager at UCL, and Vicki Baars (Acting Head of EDI, UCL) present their work on applying systems thinking to the prevention of sexual misconduct in Higher Education. Part One can be found here.

November 25th is the United Nations International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. It launches 16 days of activism on reducing gender-based violence ending on the International Human Rights Day. Nearly 1 in 3 women globally will experience some form of harassment or violence based on their gender, and recent events in the UK have highlighted the endemic and persistent nature of violence against women. The statistics are worryingly clear – there are few safe spaces for women to exist free from the spectre of sexualised attention or violence. 81% of women state that they have experienced sexual harassment in a public space (All Party Parliamentary Group, 2021), and the recent deaths of Sabina Nessa Sarah Everard are just two of many examples of women killed or assaulted whilst going about their daily lives. Violence towards women in the home reached unprecedented levels during the UK COVID-19 lockdown (ONS, 2020) and workplaces are similarly unsafe with over half of women having experienced sexual harassment in the workplace (TUC, 2019).

Sexual misconduct in Higher Education

All forms of sexual harassment, wherever they occur, are damaging and unacceptable[1]. Sexual harassment in the workplace and education is particularly pernicious in that it reduces women’s access to power and resources that make them less vulnerable to abuse. Institutions have a duty under the Equality Act 2010 to ensure that women are protected from workplace harassment and so understanding the causes of such behaviour are critical to initiatives to prevent it. In Higher Education staff to student sexual misconduct is unacceptably high. The 2018 Power in the Academy report revealed that 41% of current or past students have experienced at least one instance of sexualised behaviour from staff, with 1 in 8 current students reporting that they had experienced being touched by a staff member in a way that made them feel uncomfortable. A more recent survey of UK students on sexual misconduct found that 56% of respondents had experienced sexualised behaviour from university staff including touching, explicit messages, catcalling, sexual assault, and rape (Brookes and Dig-In, 2019). The majority of cases of staff to student sexual misconduct are carried out by men towards women, although there is also an unacceptable minority of other patterns of gendered misconduct.

Using behaviour change science to prevent sexual misconduct within UCL

In 2019 the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion team in the Office of the President and Provost at UCL commissioned the UCL Centre for Behaviour Change to support them to use behaviour change science to develop an institutional response to prevention of a range of problematic behaviours such as bullying, harassment and sexual misconduct. The report ‘Preventing Sexual Misconduct at UCL: Recommendations from a Behavioural Systems Mapping Investigation’ describes the methods and findings of a whole of system approach to understanding the issue of staff to student sexual misconduct within higher education.

Behavioural and systems approaches to change

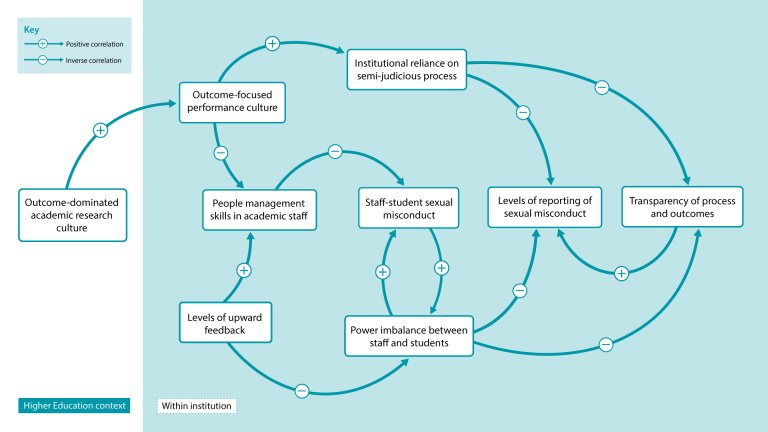

Any given behaviour, such as sexual harassment of one person to another is located within a complex web of causal influences. Behavioural systems mapping is an emerging methodology for identifying and understanding the role of behaviour within systems. It has been used to develop policy recommendations for complex issues such as how to encourage population-wide adoption of carbon saving technologies within housing (Chadwick and Hale, 2021), and food waste (WRAP, 2021). It identifies the actors (people, institutions), behaviours and influences influencing the expression of a behaviour and describes how they are related to each other. The most common output of this process is a behavioural systems map which visually represents the key features of a system which can be used to develop recommendations for interventions to bring about behavioural change.

Applying behavioural systems mapping to sexual misconduct

The term sexual harassment refers to behaviours of a sexual nature which violates an individual’s dignity or makes them feel intimidated, degraded or humiliated. Harassment exists on a continuum, from sexualised language (e.g. commenting on appearance) to sexual assault (e.g. rape). The method of behavioural systems mapping to understand the specific factors at play in the expression of staff to student sexual misconduct within UCL specifically but also drawing upon research within the wider sector.

The report describes six features of an organisational system that work synergistically to enable staff to student sexual misconduct (see Figure One). It outlines how structural inequalities in power and position within wider society interact with interpersonal and organisational processes to create and magnify students’ vulnerability and exposure to sexualised behaviour from academic supervisors. Based on the map, and consultation with senior stakeholders within the organisation, the report makes recommendations for how the organisations processes and procedures can be modified to restructure the system to discourage behaviours enabling sexual misconduct, and encourage behaviours associated with its prevention. It highlights the importance of multiple points of co-ordinated intervention within the system rather than simply locating the problem, and therefore the solution, within ‘problematic’ individuals.

From analysis to action

The outcomes of this work have already been used by UCL to implement changes within the institution to equalise power between staff and students. UCL has introduced thesis committees to tackle the closed nature of supervision, policies are being reviewed taking these research findings into account and environmental investigations are being used to identify and address cultural issues. Further work is planned through a prevention of harmful behaviours working group under the UCL EDI committee, with the aim of spearheading different aspects of the response, exploring both preventative and restorative justice mechanisms. More information about the work of the UCL EDI team and the report can be found here. The Organisational Development team within UCL are also building on this method to explore systems approaches to culture change within higher education to improve researcher wellbeing.

Figure One: System themes influencing staff-student sexual misconduct within UCL

Kelsey Paske is an independent consultant specialising in equality, diversity and inclusion issues within the workplace: https://www.kelseypaskeconsulting.com E: kelsey@kelseypaskeconsulting.com

Paul Chadwick is Consultant Clinical and Health Psychologist, Deputy Director and Associate Professor at the UCL Centre for Behaviour Change: E: p.chadwick@ucl.ac.uk T:@drpaulchadwick

More information on the work of Dr. Paul Chadwick and the UCL Centre for Behaviour Change on gender-based violence can be found here.

[1] Sexual misconduct and harassment exist on a continuum of behaviours. All forms of sexual harassment are harmful and unacceptable. We use the terms ‘major’ and ‘minor’ forms of sexual misconduct to help differentiate between behaviours that might differ in terms of impact. However, we would like to make clear that all forms of sexual harassment are harmful and unacceptable, and that even ‘minor’ forms of misconduct can have extremely damaging impacts for an individual.

Close

Close