Applying behavioural science to reduce bullying, harassment and sexual misconduct within academia

12 January 2021

In the first of a two-part blog series, CBC Deputy Director Dr Paul Chadwick, and Kelsey Paske, former Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Manager at UCL reflect on their experiences of applying behaviour change science to improve working lives of staff within higher education.

Bullying and harassment is endemic within academic institutions. The Wellcome Report into research culture indicated that 43% of researchers have experienced bullying and harassment, and 61% have witnessed bullying and harassment of others (Wellcome Trust, 2020). Whilst there has been no attempt to quantify the financial costs associated with bullying and harassment in academia, research in other sectors indicate that they are likely to be high. Costs associated with bullying and harassment in the UK National Health Service have been conservatively estimated at £2.28bn arising from the costs associated with turnover, productivity, sickness and employee relations (Kline & Lewis, 2019).

The task of addressing bullying and harassment in academia often sits with professional services in Human Resources (HR) departments, or Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) teams. The dominant approach to address these issues is through the provision of training designed to raise awareness of the problem and its impact. There are few formal evaluations of training interventions to reduce bullying and harassment, although anecdotal evidence suggest such initiatives increase awareness without a corresponding change in behaviour. The terms ‘bullying’ and ‘harassment’ refer behaviours in which one person intimidates or humiliates another and can be intentional or unintentional. The definition of harassment is also grounded in law through the Equality Act 2010 which relates to unwanted conduct related to protected characteristics such as an individual’s gender, ethnicity and sexual orientation. Despite recognition of the behavioural nature of bullying and harassment the theories and methods of behavioural science are not routinely applied to intervene to reduce occurrence.

From 2019-2020 a partnership between the Centre for Behaviour Change (CBC) and the Equality, Diversity and Inclusion team at UCL explored how behavioural science could be applied to reduce bullying and harassment. The partnership involved two projects:

- Reducing bullying and harassment; professional services staff within UCL were trained to apply the Behaviour Change Wheel framework (Michie, Atkins, & West, 2014) to develop and refine policies and procedures to reduce bullying and harassment within the institution.

- Preventing sexual misconduct; the CBC was commissioned to apply the methodology of behavioural systems mapping to describe systemic influences contributing to sexual misconduct within higher education institutions

This blog describes the learnings from the first project, whilst learnings from the second will be presented in part two of this series.

Using the Behaviour Change Wheel to reduce bullying and harassment

EDI and HR staff within UCL were trained in the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) framework and used the approach to review internal and sector-wide training initiatives for reducing bullying and harassment. The review led to the development of four recommendations for how behaviour change science could be used to improve the impact of training initiatives to prevent bullying and harassment within higher education institutions.

1. Be clear about the behaviours that need to be changed; training packages designed to prevent bullying and harassment typically focus on the expression of unwanted and harmful behaviours. The focus is primarily on changing the behaviour of individuals who may intentionally and unintentionally behave in ways that intimidate or humiliate others. However, effective prevention of bullying and harassment might require consideration of actors other than those who directly express such problematic behaviours and may usefully include the behaviours of those that witness bullying and harassment, and those tasked with the investigating such incidents. Table One illustrates some of the different actors and behaviours that we identified could be targeted to reduce bullying and harassment within an organisation

Actor | Target behaviours relating to bullying and harassment |

Perpetrators of bullying / harassment behaviour |

|

Recipients of bullying and harassment behaviour |

|

Managers |

|

Witnesses to bullying and harassment behaviour |

|

Behaviours relating to bullying and harassment can be broadly classified as antisocial (e.g., belittling, sexual misconduct) or prosocial in nature (e.g., intervening to prevent such actions, offering support). Whilst the need to focus on reduction of antisocial behaviours is obvious, increasing prosocial behaviours could also reduce expression of, and harms associated with, behaviours that intimidate and humiliate (Bierhoff, 2002).

From the standpoint of behaviour change theory and practice the behaviours in Table One will impact the expression of bullying and harassment in different ways, and will be caused by different patterns of influence. Interventions to reduce antisocial behaviours will not necessarily increase prosocial behaviours, and vice versa. Similarly, efforts to change one form of pro- or antisocial behaviour will not necessarily lead to changes in others in that category. Most training-based approaches to tackling bullying and harassment are not sufficiently specific about the behaviours that need to be changed. When designing training packages to tackle bullying and harassment HR/EDI professionals should be clear about the behaviours that they want to influence and ensure that the content of training is specifically targeted towards changing those behaviours.

2. Use models and frameworks to identify influences on bullying and harassment behaviours; at the heart of the BCW framework is the Capability-Opportunity-Motivation-Behaviour (COM-B) model which outlines the necessary conditions for expression of a behaviour. The COM-B model can be used to systematically identify the various influences on behaviours targeted by training interventions. This is known as a COM-B diagnosis. Applying COM-B to the behaviours in Table One identified a wider range of influences on the expression of bullying and harassment behaviours than is usually considered in existing training approaches. To illustrate this, let’s use example of increasing interventions by who might witness bullying or harassment – so called ‘bystander interventions’. If the target behaviour is for staff members to intervene to stop bullying occurring during a team meeting, a COM-B diagnosis may point to the following influences:

- Capability: they will need to know what constitutes bullying and how to differentiate it from strong feedback, and have the required interpersonal skills to intervene in a way that does not lead to unhelpful escalation.

- Motivation: they will need both the desire and confidence to use their knowledge and skills, and believe that that the outcomes of taking action will be positive

- Opportunity: they will need to work in a team and departmental culture that is broadly supportive of such actions.

Interventions to change behaviour are more likely to be successful if they target the specific influences on its expression. Approaches that do not tackle the full range of influences on bullying and harassment behaviours are less likely to be successful in bringing about the desired change.

Models and frameworks from behavioural science such as COM-B, and the more granular Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF; (Atkins et al., 2017)) should be used to help HR/EDI professionals explore the full range of influences that may be at play in the expression of behaviours related to bullying and harassment.

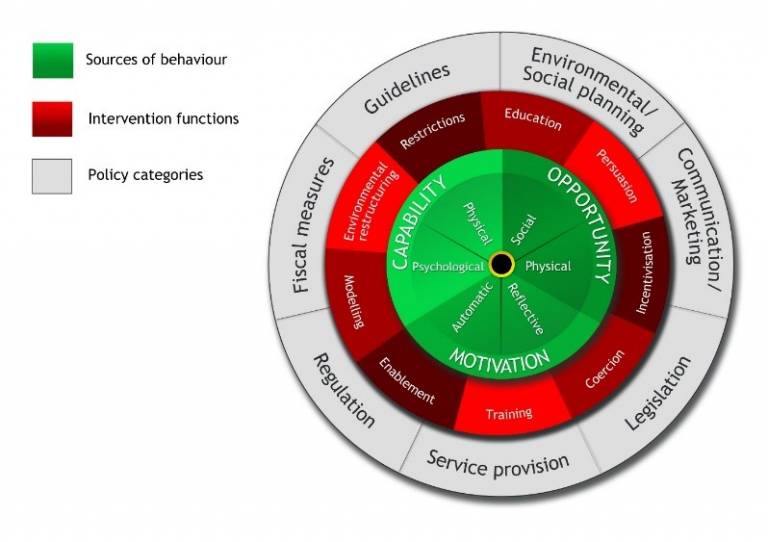

Figure One: The Behaviour Change Wheel (Michie et al., 2014)

3. Use a broad range of targeted intervention strategies to change behaviour; training initiatives to reduce bullying and harassment in academia typically focus on increasing awareness of the issue by educating staff about what constitutes problematic behaviour and using persuasive techniques such as witness statements to highlighting its negative impact. Whilst education and persuasion are powerful techniques for tackling some aspects of capability and motivation, they may not be particularly effective at changing other influences on behaviours relating to bullying and harassment. They would not, for example, help staff acquire the interpersonal skills needed to give feedback constructively or intervene to stop an episode of bullying in a tactful way. The BCW describes 9 broad intervention types that can be used to bring about change to influences on behaviour (see Figure One, intervention types are represented by the middle red ring), along with guidance to help designers use intervention types most likely to bring about change.

Returning to our example of encouraging staff to intervene to stop bullying, an intervention might use education to help staff understand what behaviours constitute bullying and harassment (targeting capability), persuasion to help them understand the psychological and physical harms that arise from being exposed to such behaviour (targeting motivation), and training and modelling to help them acquire the interpersonal skills and confidence to intervene in a firm but tactful way (targeting capability, opportunity and motivation).

When designing training interventions to prevent bullying and harassment HR/EDI professionals should look to incorporate a wide range of intervention types to bring about change to the influences on target behaviours. As well as incorporating techniques to educate and persuade people to take action, they can also use strategies which equip staff with the skills required to behave in ways that limit the expression and impact of harmful interactions, and develop resources to will support such this.

4. Ensure that training interventions are embedded and reinforced within the institution; Developing and implementing training, even if it targets the key actors, behaviours and influences will fail to have impact if the desired behaviour changes are not supported by institutional policy and procedure. The BCW describes 7 different ways that institutions can embed and reinforce change. These are known as policy options (see Figure One; policy options form the grey outer ring). Whilst a training course might successfully increase the commitment to reporting instances of harassment, if the processes to report are unclear, or there is a lack of trust in or transparency over what happens next, the institutional system will work against the purpose of the intervention. This will fuel an unhelpful disconnect between the behaviour of the individual and the culture of the organisation. This could be dealt with by developing new guidance for reporting such behaviour, an internal communications/marketing strategy to increase people’s awareness of this, and altering the regulations which outline and govern behavioural standards for staff.

In order to enable meaningful and sustainable change, higher education institutions need to reflect critically on how the wider institutional context may operate to facilitate or mitigate the impact of training-based interventions. Interventions that are not reinforced by the policies and procedures of the institution are unlikely to take effect and deliver the desired reduction in bullying and harassment levels. The development of training approaches to bullying and harassment should therefore inform, and be informed by, wider approaches to organisational development and governance.

Beyond bullying and harassment: Implications for EDI/HR within higher education

Most EDI and HR professionals would agree that their primary role is to shape behaviour of employees to improve working lives, the efficiency of the working environment, and help the organisation achieve its mission and vision. Behaviour is often the missing link between the laudable ambitions of organisational policy and what is achieved by the often disappointing reality of implementation. Our experience of applying the Behaviour Change Wheel framework to the issue of bullying and harassment leads us to believe that behavioural science could make a meaningful positive impact on other areas of organisational functioning. Institutions are increasingly held accountable for the ethics of their actions. Workforce wellbeing, and the equality of opportunity and progression available to employees are now key issues upon which the performance of an organisation is judged. In response to increased scrutiny on issues of equality, diversity and wellbeing organisations can be forced into ‘reactive’ mode, reaching for ‘off the shelf’ solutions in order to demonstrate accountability. Whilst such a strategy will have some benefits, it may not deliver the transformative change required to make a meaningful difference. Each institution is unique and the nature of its work, combined with the norms and standards for the sector may mean that ‘off the shelf’ solutions could fail to make an impact, or misfire to make things worse. The use of theories and methods of behaviour change could help HR/EDI professionals take a more organic and targeted approach which is tailored to the specific needs of the institution, supporting teams to maximise the impact of their interventions and making more effective use of institutional resources.

For any questions, please get in touch with Paul Chadwick. Part Two of the blog will focus on the systems map application and be released early 2021.

More information on the Behaviour Change Wheel approach can be found by accessing the Achieving Behaviour Change Guides.

If you have been affected by the issues raised in this blog post please consult the following UCL resources for information and support:

References

Atkins, L., Francis, J., Islam, R., O’Connor, D., Patey, A., Ivers, N., … Michie, S. (2017). A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implementation Science, 12(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9

Bierhoff, H. (2002). Prosocial Behaviour. Hove: Psychology Press.

Kline, R., & Lewis, D. (2019). The price of fear: Estimating the financial cost of bullying and harassment to the NHS in England. Public Money and Management, 39(3), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2018.1535044

Michie, S., Atkins, L., & West, R. (2014). The Behaviour Change Wheel - A Guide To Designing Interventions. Silverback Publishing. Retrieved from http://www.behaviourchangewheel.com/

Wellcome Trust. (2020). What researchers think about the culture they work in. Retrieved January 6, 2021, from https://wellcome.org/reports/what-researchers-think-about-research-culture

Close

Close