Decarbonising heat in homes: Applying behavioural science to the whole system

5 May 2021

CBC Deputy Director Dr Paul Chadwick and Senior Research Associate Dr Jo Hale share key insights for decarbonising heat in homes, learned through working with the Decarbonisation of Homes in Wales Independent Advisory Group.

Changing the way we heat our homes will be essential for reaching Net Zero in the UK. At the moment heating accounts for around a third of the UK’s carbon emissions. Whilst many households are switching to smart meters, green energy tariffs and other low-carbon initiatives, there is still some way to go before housing is carbon neutral. Households of all kinds will need to be supported to make low-carbon changes, which will mean retrofitting homes at a national scale.

In 2019 the CBC worked with the Decarbonisation of Homes in Wales Advisory Group to develop a plan for the decarbonisation of housing in Wales. The lessons we learned from working together have fed into a joint evidence submission to the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Committee inquiry into decarbonising heating in homes across the UK.

In this blog post we share some of the key points from our evidence submission, as well as our recommendations to the Committee.

What lessons can be learned from past and current policies?

Three principles underpinned our approach to developing a strategy for the decarbonisation of housing in Wales. These principles were derived from analysis of policies that have so far failed to deliver decarbonisation at scale:

- The importance of a long-term policy certainty. There have been 13 significant changes in UK residential energy efficiency policy since the introduction of the Energy Efficiency Commitment in 2002, causing uncertainty and confusion. A stable policy environment creates the necessary conditions in the energy ecosystem to allow homeowners and industry to understand what needs to be done and to believe that it is both necessary and beneficial.

- The importance of understanding human behaviour. The behaviour of people within homes will make a critical contribution to the success of decarbonisation efforts. Inhabitants of homes need to behave in ways that reduce the demand for heating in the first place, and the adoption of low carbon heating technologies will only deliver benefits when people install and use them correctly within homes. Therefore, it is important to design energy efficiency policy with an understanding of the behaviour of owner-occupiers, landlords and tenants at its heart.

- The importance of a systems perspective of the problem. Focusing solely on the actions of owner-occupiers, landlords and tenants neglects the role of other actors in the energy system, such as banks, building societies, builders, builders’ merchants, and others. To achieve the use of low-carbon heating technologies at scale the actions of all actors in the system need to work in a coordinated way. Taking a systems perspective can help to improve decision-making and avoid unintended consequences that have characterised previous low-carbon heat policies.

Recommendations for developing policy to support mass decarbonisation

Our evidence submission focussed on illustrating the application and value of using frameworks from behavioural science to develop policies that placed behaviours responsible for decarbonisation front and centre.

Recommendation 1: Apply a systematic approach to identifying the behaviours involved in low carbon heating

Previous approaches to decarbonisation policy have focussed primarily on behaviours of homeowners, and their decision-making processes in particular. However, the behaviour of homeowners are influenced by the behaviours of other actors in the system, such as those responsible for advising them on which technology to retrofit, and the actions of local and national government officials who might set tariffs and outline standards, costs and competencies for retrofit activities.

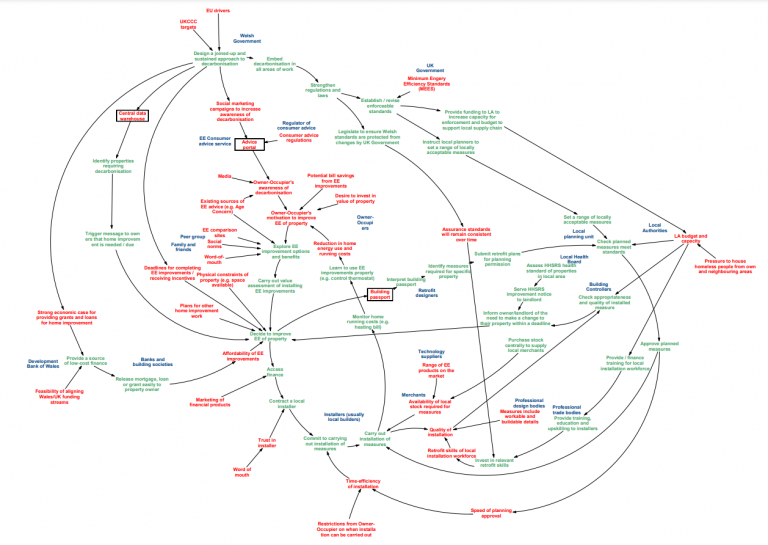

Systems mapping methods can help to identify and describe the interconnections between behaviours of different actors within the housing energy system, and the factors that influence them. The behavioural systems map in Figure One presents some of the key actors, behaviours and influences involved in energy use within the Welsh housing system, illustrating the interplay between local and national government, supply chain and financial services. The map was used by advisory group members to draw up the recommendations in Better Homes, Better Wales, Better World.

Figure One: Behavioural Systems Map of the Welsh Housing System

Recommendation 2: Use established behavioural science frameworks to understand the influences on these behaviours and develop interventions to change them

Once the key behaviours relevant to decarbonisation have been identified we recommend using an established behaviour change model and framework to understand the drivers of people’s behaviours and develop interventions to change them. A summary of the method we used to develop the recommendations in Better Homes, Better Wales, Better World can be found in Achieving behaviour change: A guide for national government.

What are the barriers and enablers for homeowners to decarbonise heating?

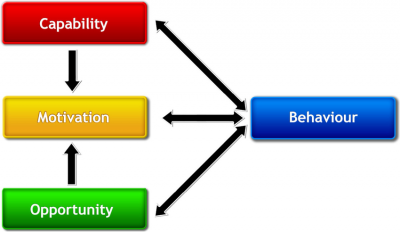

The COM-B model identifies three factors that need to be present for any behaviour to occur: capability, opportunity and motivation (Figure Two). These three factors form an interacting system with behaviour. If just one of these is not in place the desired behaviour will not occur. Therefore, it is important to not only remove barriers to the behaviours required for scaling up low carbon heating technologies, but also put in place enablers to support capability, opportunity and motivation where needed.

Figure Two: The COM-B model

We used the COM-B model to classify a range of known influences on homeowners’ adoption of low-carbon heating. Explore them below:

- Capability influences

- Homeowners lack knowledge of what to do to improve the energy efficiency of their homes, and where to get trustworthy advice

- Poor public understanding of terms such as ‘energy’ and ‘carbon’

- Opportunity influences

- Lack of capacity within network of small builders to invest in developing capability for retrofit work - many small builders have all the work they need doing conventional repair, maintenance and improvement to homes

- Electoral cycle contributes to policies focussed on short-term costs rather than long-term value, resulting in a fluctuating policy environment discouraging large-scale residential decarbonisation.

- High price of retrofit work to consumers until a steady pipeline of work is established for contractors and installers.

- Few, if any, financial products specifically designed for improving the energy efficiency of homes

- Lack of a steady pipeline of work has prevented firms engaged in residential energy efficiency from investing to train, to take on apprentices and new staff, to innovate, and to drive down costs.

- Data on the impact of installing energy efficiency measures on residential energy consumption has not been captured or used to facilitate continuous improvements. The result is too much underperforming work which damages the reputation of all energy improvements and slows progress towards net zero in 2050

- Information on energy and carbon performance is presented in many different ways, which makes comparisons between different measures difficult. This is true of both operational and embodied carbon.

- Conservation areas in many towns and cities prevent the installation of necessary measures to the exteriors of homes.

- High visibility of anthropogenic climate change deniers within the mainstream and social media.

- Improving home energy efficiency is not socially normal in the way that other improvements are (e.g. new kitchens and bathrooms).

- Lack of strong cultural narrative to promote desirability of retrofit measures (e.g. no equivalent of television programmes such as Grand Designs to model and celebrate retrofit)

- Motivation influences

- Disruptive nature of the work involved in installing low carbon technologies in homes

- Poor reputation of the value of energy efficient home improvements due to widespread examples of poorly designed or installed measures (e.g. external wall insulation)

- Uncertain economic environment reduces consumer motivation for investment in low carbon technologies

- Mistrust in government initiatives to support low carbon technologies due to frequent changes of policy

- Lack of an equivalent of the Treasury’s Enhanced Capital Allowances regulations to allow private landlords to offset the cost of some types of new energy efficiency measures against their tax liabilities

- Homeowners will not recover the costs of installation for most low carbon technologies via energy savings. Previous initiatives focused on this (e.g. the Green Deal’s Golden Rule) but no other home improvements are expected to pay for themselves out of operational savings.

- Lack of an equivalent of the Treasury’s Enhanced Capital Allowances regulations to allow private landlords to offset the cost of some types of new energy efficiency measures against their tax liabilities

How can a behaviour change framework help design policy interventions that support the transition to low-carbon heat?

Interventions are likely to be successful if they target the underlying influences on the target behaviour. However, homeowners and households are not the only actors in the system who will need to take action. Decarbonisation policies will need to deliver a variety of interventions that support coordinated behaviour changes across all key players. This will mean understanding and modifying the underlying influences on a wide range of behaviours.

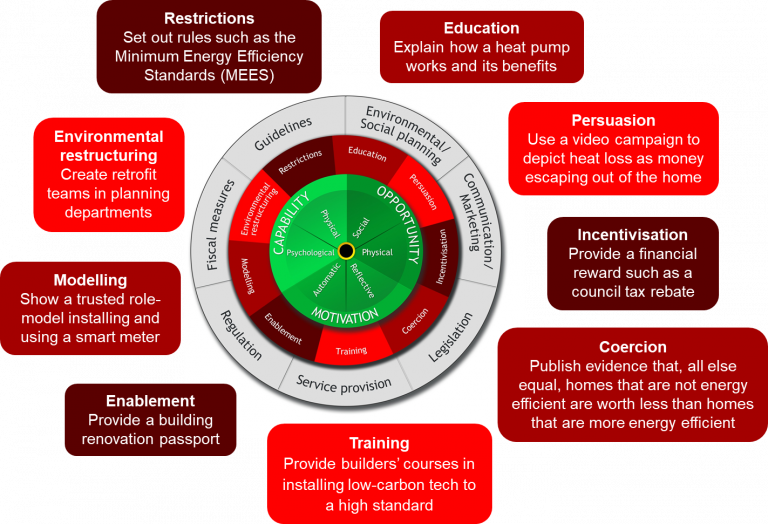

The Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) is a systematic framework for developing interventions by modifying capability, opportunity or motivation factors influencing behaviour. For the nine types of intervention described in the BCW, Figure Three gives examples of how they could be used in the decarbonisation of heating.

Figure Three: Examples of how the Behaviour Change Wheel intervention functions could be used in the decarbonisation of heating.

An illustration using the Green Home Grants scheme

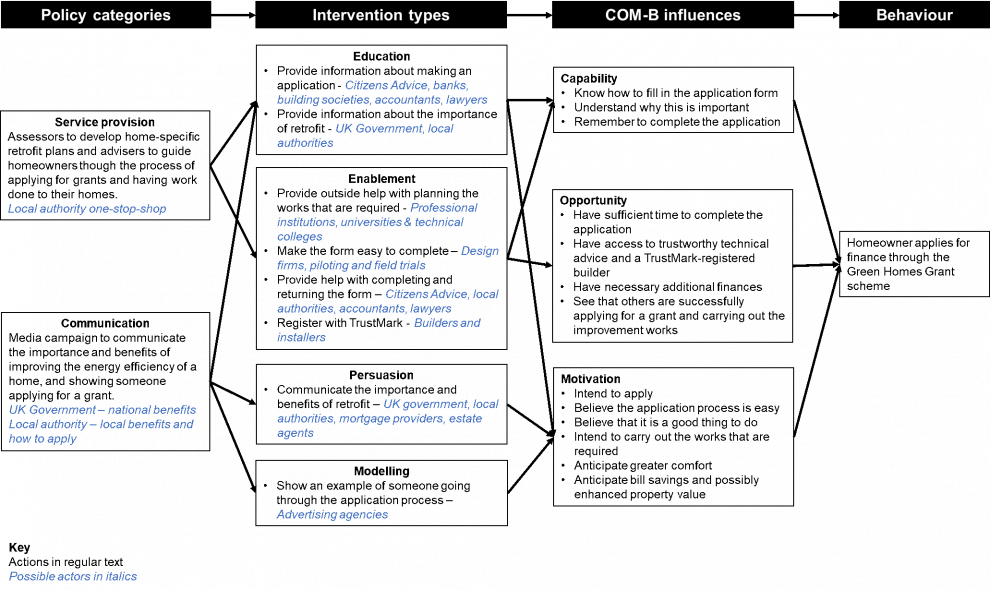

The nine types of intervention in the BCW framework can be supported by seven categories of policy actions. Figure Four illustrates the whole process of applying the behaviour change wheel to the challenge of getting homeowners to apply for finance through the Green Home Grants scheme. This example was adapted from the work of Ellie Kuitunen of Arup and the University of Derby.

Figure Four: Illustration of applying the Behaviour Change Wheel to the uptake of Green Home Grants

Combining multiple intervention types and policy options may be necessary for a large or complex behaviour change task. In this illustration, four different intervention types were identified and combined to address homeowners’ capability, opportunity and motivation. To deliver these types of intervention, the diagram shows how two policy options (Service provision and Communication) could be used in tandem.

To decarbonise heating in UK homes, coordinated action will be needed across all levels of the system. The framework-based approach we advocate can help national and local government within the UK to develop co-ordinated policies that engage partners to deliver a range of targeted interventions which support people to use less energy to heat their homes.

Read the full evidence submission here

Read our recommended approach in Achieving behaviour change: A guide for national government

For screen-readable versions of the diagrams on this page please contact Dr Jo Hale, who would be pleased to provide them.

Close

Close