International Women's Day: The Female Voice in Medieval Medicine

8 March 2022

ASE’s Lorna Webb examines women’s contribution to medieval manuscripts for International Women’s Day.

When we think of the writings of the Middle Ages there is often an assumption that they have been written (and read) by men. Works such as Beowulf, which deals with themes such as how groups of men socialise and function in society, as well as containing a discussion on what makes a good leader/king, is clearly written with a male audience in mind.

The female characters are scarce, almost outsiders in a masculine world, and the predominate female character is deemed a “monster” and defined by her relationship with a male character (Trilling 2007). This is a theme that follows through Early Medieval literature with female characters reduced to background characters or associated with morally ambiguous acts such as in Judith, another poem found in the same manuscript as Beowulf.

More practical texts, such as medical texts, are often automatically assumed to have been written by men, continuing this theme of the medieval world being solely experienced through a male gaze. Though marginalised, mostly due to the Catholic Church’s teaching that women were second to men in all things, there are works of literature attributed to women during this period of history on a wide range of subjects (Dinshaw and Wallace 2012). Science and medicine was no exception. In the field of gynaecology and obstetrics the female voice is important as giving birth during this period, as it is to an extent in the present, was very dangerous and could be life threatening (Phillips 2013).

A good example of women’s medicine made for and written by a woman is the Trotula of Salerno. Written in the 12th century in southern Italy this work is a group of three texts outlining aspects of medicine for women (Green 2002). These three texts are titled: The Conditions of Women, Treatments for Women, and Women’s Cosmetics. These cover a range of subjects from child birth to hair care, menstruation to making a type of lipstick. The Trotula has been copied many times and appears in over 200 manuscripts in Latin, French and Italian and the dating for these manuscripts ranges all the way to the 15th century.

The writing in the manuscript itself is very practical. The first two sections focus on childbirth and “the treatment of women” as well as how to look after new born children. The last section is about cosmetics and would not be out of place in a women’s magazine today. The content deals with how to remove hair, how to make your hair thicker, how to look after teeth, mouth, lips and face. Here is an English translation of one of the recipes which is for an early type of lip balm to colour the lips:

“Skim honey, to which they add a little white bryony, red bryony, cucumber, and a little bit of rose water. They boil all these things until [it is reduced] by half. With this ointment, women anoint their lips.” (Green 2002)

This inclusion of cosmetic practices may seem trivial, but the work shows a great knowledge of cultures beside that of western Christianity and references Muslim practices (Green 2002). By being copied and with so many versions available the Trotula has a wide reach of audience and is even mentioned by Chaucer in the Wife of Bath’s tale in the Canterbury Tales. The Trotula is so significant because it shows that women were writing about scientific subjects and were widely respected and well-known for their knowledge

During the centuries following the protestant reformations across Europe and the artistic and scientific renaissance, the medieval works from the former centuries dropped out of use. Even as late as the 19th century the attitudes towards works written by women and on subjects such as gynaecology were sometimes omitted or untranslated in reworking of medieval texts. The legacy of female medical practitioners from medieval centuries has been greatly overlooked (Green 2008) but unpicking the female point of view in these texts has implications which can bring the female voice from the outside into the centre of the medieval masculine world.

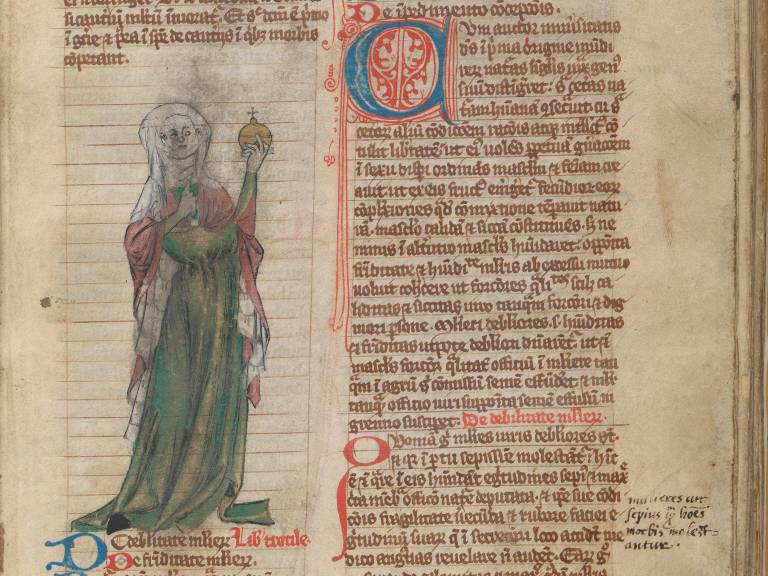

Cover image is pen and wash drawing meant to depict "Trotula", clothed in red and green with a white headdress, holding an orb. Image from "Book of learned medical treatises with some additional practical texts" (Miscellanea Medica XVIII), Wellcome Library MS 544, p. 65

References

Dinshaw, C. & Wallace, D., 2012. The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women's Writing

Green, M., 2002. The Trotula: an English translation of the medieval compendium of women's medicine. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Green, M., 2008. Making women's medicine masculine: the rise of male authority in pre-modern gynaecology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Phillips, K., 2013. A cultural history of women in the Middle Ages. London ; New York: Bloomsbury.

Trilling, R., 2007. Beyond abjection: the problem with Grendel's mother again. Parergon, 24(1), pp.1–20.

Close

Close