Embedding sustainability into your teaching and learning

This toolkit aims to support staff from all faculties and disciplines to develop educational experiences that empower and enable UCL students to become leaders and activators in the global transition.

28 April 2023

The endeavour to embed sustainability into curricula has become widely known as Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), defined by UNESCO (2021) as:

"the process of equipping students with the knowledge and understanding, skills and attributes needed to work and live in a way that safeguards environmental, social and economic wellbeing, in the present and for future generations."

There are numerous definitions of ESD. They all share a focus on the relationships between the environment, society and economy and the links between present and future. Most advocate teaching and learning across both cognitive and affective domains to support development of knowledge, skills, attributes and values (Sterling, 2011, p.9).

Return to the top of this page.

Climate change is the biggest single challenge that humanity has ever faced. It is vital to equip students with the knowledge, skills and values that they need to thrive in a rapidly changing world.

Beyond the obvious drivers for and impacts of climate catastrophe lies a whole host of social, economic and environmental challenges that require urgent attention. Climate justice, climate education, biodiversity loss, climate policy, etc, are a few issues that our HE graduates face immediately on leaving education. It is no wonder that an international survey of 10,000 young people aged 16-25 revealed that 84% are moderately worried by climate change. Nearly a half of all respondents report feelings such as anxiety, anger, or helplessness that mar their experience on a daily basis (Hickman et al, 2021).

There is a growing drive in higher education (HE) institutions globally to turn this trend around by embedding ESD in curricula and provide a more hopeful, transformative style of education that leaves students with a strong sense of agency and hope for the future (Bourn, 2021).

UNESCO (Berlin Statement, 2021, p.2) has defined ESD as the

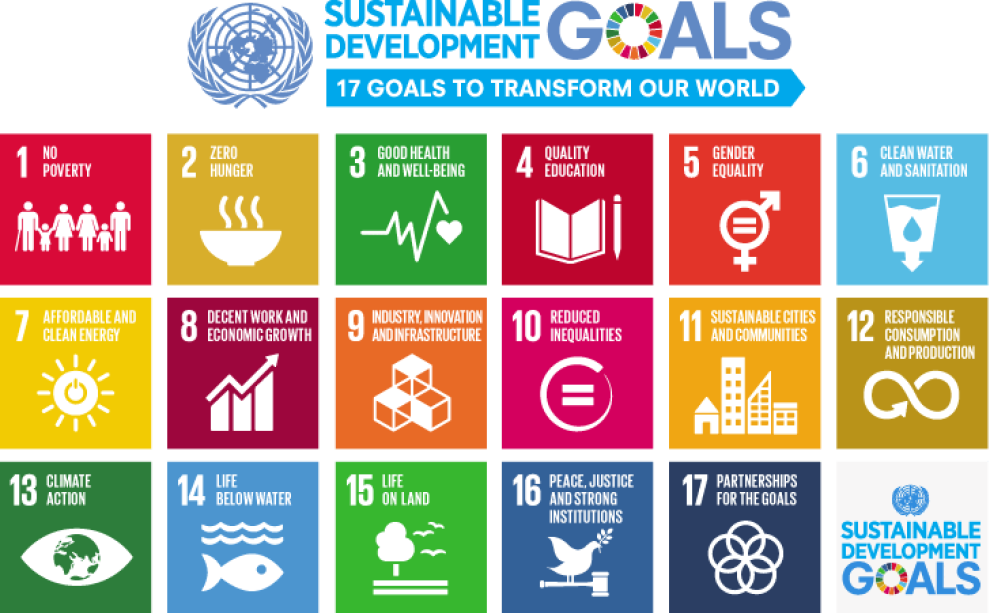

“enabler of all 17 Sustainable Development Goals… the foundation for the required transformation…[to] a sustainable future”.

The spread of activities described by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) gives ESD a broad relevance beyond pure environmental science, identifying social, historical, and political issues, among others.

UCL is London’s global university and as such the institution must take a lead on embedding ESD in curricula and extra-curricular all our educational programmes and activities. In line with this, UCL has committed to to all students having the opportunity to study and be involved in sustainability by 2024 (Sustainable UCL, 2019).

At a national level, there is increasing uptake of ESD in criteria used by chartering and accreditation bodies (e.g. QAA ESD Drive, The Engineering Council AHEP4). The latest review of the UK Professional Standards Framework used by Advance HE to assess HE fellowship applications also now includes references to ESD in teaching practices.

Return to the top of this page.

Here we describe a process which is designed to help you identify ways in which you might integrate ESD in your teaching if you are not doing so already. Whether you are working with a single activity, an assessment, a module or a whole programme, you are likely to gain insights that can get you started. If you are working with a whole programme, then bear in mind that this is a relatively long-term process, and you may wish to start small. See references section for further resources on this.

Step 1: Map your area of work against UNESCO competencies

Step 2: Develop new directions and activities for students with ESD

Step 3: Adopt pedagogies and assessments to enhance cognitive and affective learning

Step 4: Find opportunities in the wider UCL community to foster and support ESD.

1. Mapping ESD competencies – what you already do

One of the best places to start thinking through how you can embed ESD is to know what you already support by mapping the UNESCO competencies in your current teaching. Most definitions of ESD are as broad as UNESCO’s “knowledge and understanding, skills and attributes needed to work and live in a way that safeguards environmental, social and economic wellbeing…”. This does not easily translate to learning outcomes and activities. However, UNESCO and other organisations have identified eight competencies that encompass the behaviours, attitudes, values and knowledge which facilitate safeguarding the future (see box, below).

- Read the UNESCO competencies (adapted from UNESCO 2017 p10)

Systems Thinking

To recognize and understand relationships; to analyse complex systems; to think of how systems are embedded within different domains and different scales; and to deal with uncertainty.

Anticipatory Competency

To understand and evaluate multiple futures – possible, probable and desirable; to create one’s own visions for the future; to apply the precautionary principle; to assess the consequences of actions; and to deal with risks and changes.

Normative Competency

To understand and reflect on the norms and values that underlie one’s actions; and to negotiate sustainability values, principles, goals, and targets, in a context of conflicts of interest and trade-offs, uncertain knowledge and contradictions.

Strategic Competency

To collectively develop and implement innovative actions that further sustainability at the local level and further afield.

Collaborative Competency

To learn from others; to understand and respect the needs, perspectives and actions of others (empathy); to understand, relate to and be sensitive to others (empathic leadership); to deal with conflicts in a group; and to facilitate collaborative and participatory problem solving.

Critical Thinking Competency

To question norms, practices, and opinions; to reflect on own one’s values, perceptions and actions; and to take a position in the sustainability discourse.

Self Awareness

To reflect on one’s own role in the local community and (global) society; to continually evaluate and further motivate one’s actions; and to deal with one’s feelings and desires.

Integrated Problem Solving

The overarching ability to apply different problem-solving frameworks to complex sustainability problems and develop viable, inclusive, and equitable solution options that promote sustainable development, integrating the competences mentioned above.

These provide a way for you as an educator to identify activities and extend learning opportunities that can be embedded in your different disciplinary curricula and courses. For example, you may already include some team activities in your courses and so your students will already be developing a Collaborative Competency.

Sustainability is crosscutting in the same way as other educational themes in higher education (HE) agendas such as employability, global citizenship, decolonising the curriculum and EDI. It requires a whole-person orientation to the world that includes cognitive and socio-emotional understandings as well as motivational and normative aspects.

The UNESCO competencies are broadly agreed upon and widely used (see Rieckmann, UNESCO, 2018, pp.39-60). Most disciplines require some or all competencies and it is helpful to know which competencies are already supported by your own disciplinary context and which are underrepresented. For example, students educated in ecology will automatically encounter systems thinking, whereas the literary arts are more likely to provide support for anticipatory and normative competencies, and social science students will most naturally develop critical thinking competencies (Sterling, 2011, pp.40-49).

All disciplines have something to offer ESD and all can contribute to a sustainable future.

- Activity – from competencies and learning objectives to assessment

Learning objective: cognitive Learning objective: socio-emotional Learning objective: behavioural Learning activity Assessment Assessed competency Example 1: English Literature

19th-century reception and context of Dickens’ description of relationships between poverty, power and crime in Oliver Twist (1838).

SDG 1, 2, 8, 10, 16Develop a sense of the different actors, their voices, experiences and their role and relationships in power dynamic surrounding the London poor. To debate issues of social justice in this context and how these issues might present in other times and contexts. Close reading. Discussion.

Role play scenarios e.g. taking character roles, policy discussion.

This could also be extended to activities outside classes e.g. visiting areas of London depicted in the book to consider how they have changed and for what reasons.Individual assessment –

Learning could form part of final essay.

Students could also be required to create a blog, poster, or short story that engages with the same issues of poverty and inequality.Assessed:

critical thinking; systems thinking; normative competencyPresent but unassessed:

integrated problem-solving; collaborative competencyExample 2: Engineering Design

Understand a range of conservation technologies, how they are used, what their benefits and limits are and to evaluate them in context of wolf conservation.

SDG 3, 8, 10, 15, 17Develop a sense of the stakeholder groups, their values and framing of wolf conservation and how these relate to their experiences. To develop a personal position in conservation debates and to consider the technologies that may help different human populations to live with large, wild animals. Project-based learning experience to design a conservation technology that aids in wild wolf management in Europe. This could involve a mix of activities both in class and outside including: visit to wolf wildlife park, interviews and talks with stakeholders. Team assessment – written project progress report. Assessed:

systems thinking; anticipatory thinking; normative thinking; self-awareness; critical thinking; integrated problem-solvingPresent but unassessed:

strategic competency; collaborative competencyThe table above can help in planning or designing a learning activity or module. Learning objectives are divided into cognitive, socio-emotional and behavioural domains (UNESCO 2017 p12). There is overlap between domains, but it can be a useful distinction particularly when thinking through what needs assessing and what it is possible to assess. In the examples, learning objectives in the behavioural domain are unassessed, although they are addressed within the learning activities. Thus it may be possible to adapt assessments to include these behavioural elements. This table is a quite comprehensive as it includes information and data from previous steps (above).

There is an excellent Futurelearn course developed by Dr Nicole Blum and Dr Frances Hunt at UCL’s Institute of Education. This is also aimed at getting started with ESD and provides further models, discussion and support for developing your practice in this area. It is a free course designed to be taken over three weeks, with a workload of three hours per week. It is highly recommended. Find more information on Futurelearn's website.

2. Developing new directions and activities for students with ESD

The SDGs offer a very good starting point for new directions and activities. It is also possible to use the SDGs to create specific learning objectives (see UNESCO 2017 pp12-45).

UNESCO (2017) has developed a useful framework in which each SDG is broken down into specific Learning Objectives that are identified as either cognitive, socio-emotional, or behavioural. For example, SDG 10 aims to achieve reduced inequalities which encompasses cognitive understandings of what inequality is, how it is measured and what drives it; socio-emotional skills and awareness involving empathy, values, communication and collaboration; and behavioural dimensions involving action-focused abilities, such as the ability to plan, implement and evaluate inequalities and strategies to reduce them.

- Activity – learning objectives

1. Read the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in full on UNESCO's website. A key question to reflect on is:

Which of the SDGs can you encompass most naturally? Commonly, you will find topics in your discipline that intersect with the concerns of sustainability. You may wish to re-frame them in order that students have a chance to think through and develop them as understandings and awarenesses for sustainability.

For example, a literary studies module that includes 19th-century English texts could raise opportunities for reflection and learning around SDG topics relating to histories of inequality, gender equality, industrialisation, water and sanitation, to name a few.

2. Read through the UNESCO ESD Learning Objectives. Download a copy from UNESCO's website (PDF). A key question to reflect on is:

Which additional or existing learning objectives could be reframed in terms of cognitive, socio-emotional, or behavioural objectives as linking to SDGs?

For example, an engineering module that includes understanding different conservation technologies. This could include socio-emotional learning objectives around:

- developing a sense of the stakeholder groups

- their values and framing of wolf conservation

- how these relate to their experiences.

3. Adopt pedagogies and assessments to enhance cognitive and affective learning

Pedagogies

There are no fixed pedagogies for ESD. Rather, to embed ESD across curricula, educators in the HE sector are challenged with supporting the development of skills and values as well as knowledge. The inclusion of values (and motivators) in particular is sometimes highlighted as the most problematic area for HE. This is because teaching values can seem to come too close to an endorsement or argument for a particular value set (McCowan, 2022). This concern has led those teaching about ESD to favour active, experiential learning and constructivist pedagogies. Students are then able to reflect on and evaluate their own position as well as that of others. In this way, they are able to discover and develop their own orientations.

Favoured pedagogical tools include:

- problem-based learning

- teamwork

- case studies

- reflection or reflective dialogue

- formal debate

- role play

- scenario planning

- imaginative reflection.

Assessment

Assessment extends learning when matched with pedagogical tools. For example, a project-based learning module might include assessments based on similar professional projects, such as project proposals, project management plans, budgets, sustainability reports, progress reports, presentations, reflective elements, etc.

Return to the top of this page.

In addition to the formal curriculum, the university environment has a diverse range of learning and engagement opportunities for ESD, and it is possible to situate ESD across different domains of activity within the HE setting. McCowan (2021) describes an approach to ESD that addresses learning across three Cs: Curriculum, Campus and Community.

- Campus: ESD by modelling

It is important that universities themselves promote and practise sustainability in their own operations and external engagements. Such efforts at ‘greening campus operations’ can be signposted for students in different ways. The aim is that they experience sustainable living and working in the immediate environment around them on a daily basis.

- Curriculum: ESD in the formal curriculum

The activities and resources suggested above are just a starting point for developing approaches to the formal curriculum.

- Community: ESD outside the formal curriculum

Opportunities exist both for the provision of elective and non-credit bearing courses on sustainability and aspects of it, but there is also the chance for facilitating and/or signposting extracurricular opportunities for engagement with sustainability projects.

This broader approach to HE provision of sustainability and climate change asks us as academics to not only consider the content of learning and teaching in the curriculum, but also to curate a range of relevant opportunities on campus and in the community (McCowan 2021). Such a holistic approach provides a rich texture of education, learning and experience that mirrors the abundance and extent of connections to ESD.

Return to the top of this page.

- View references and further reading

Bourn, D. (2021) ‘Pedagogy of hope: global learning and the future of education’. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, 13 (2), 65–78.

Climate U: Transforming Universities for a Changing Climate (PDF)

Hickman C, Marks E, Pihkala P, Clayton S, Lewandowski ER, Mayall EE, Wray B, Mellor C, and van Susteren L. (2021) “Young People's Voices on Climate Anxiety, Government Betrayal and Moral Injury: A Global Phenomenon” The Lancet Planetary Health 5: e863-e873

Hurth S, V., Sterling, S., eds. (2022). Re-Purposing Universities for Sustainable Human Progress. Lausanne: Frontiers Media SA. doi: 10.3389/ 978-2-88974-858-7

McCowan T (2022) Teaching Climate Change in the University, Transforming Universities for a Changing Climate (PDF), Working Paper Series No. 8

Rieckmann M (2012) “Future-oriented higher education: Which key competencies should be fostered through university teaching and learning?” Futures: 44 (2):127-135

Sipos, Y., Battisti, B. and Grimm, K. (2008) ‘Achieving transformative sustainability learning: engaging head, hands and heart’, International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 9(1), pp. 68–86. doi: 10.1108/14676370810842193

Sterling (2011) The Future Fit Framework (PDF)

UNESCO Berlin Declaration (PDF)

UNESCO (2017) Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives

UNESCO (2020) Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap

UNESCO (2021) Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development

UNESCO (2021) Glossary for ESD

United Nations The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022 (PDF)

Wiek, A., Withycombe, L., & Redman, C. L. (2011). Key competencies in sustainability: a reference framework for academic program development. Sustainability Science, 6(2), 203–218.

This guide has been produced by Kate Roach, Associate Professor (Education), Chair of ESD Working Group.

Reviewers and contributors were:

Nicole Blum, Senior Lecturer, IoE

Frances Hunt, Senior Research Officer, IoE

Rebecca Lindner, Associate Professor (Teaching), VPESE

Anne Preston, Associate Professor (Teaching), VPESE

Hannah Biggs, Senior Sustainability Manager, CE&IE

Simon Knowles, Head of Coordination SDG’s, VP RIGE

You are welcome to use this guide if you are from another educational facility, but you must credit the project.

Return to the top of this page.

Close

Close