Diverse life forms may have evolved earlier than previously thought

13 April 2022

Diverse microbial life existed on Earth at least 3.75 billion years ago, suggests a new study led by UCL researchers that challenges the conventional view of when life began.

For the study, published in Science Advances, the research team analysed a fist-sized rock from Quebec, Canada, estimated to be between 3.75 and 4.28 billion years old. In an earlier Nature paper*, the team found tiny filaments, knobs and tubes in the rock which appeared to have been made by bacteria.

However, not all scientists agreed that these structures – dating about 300 million years earlier than what is more commonly accepted as the first sign of ancient life – were of biological origin.

Now, after extensive further analysis of the rock, the team have discovered a much larger and more complex structure – a stem with parallel branches on one side that is nearly a centimetre long – as well as hundreds of distorted spheres, or ellipsoids, alongside the tubes and filaments.

The researchers say that, while some of the structures could conceivably have been created through chance chemical reactions, the “tree-like” stem with parallel branches was most likely biological in origin, as no structure created via chemistry alone has been found like it.

The team also provide evidence of how the bacteria got their energy in different ways. They found mineralised chemical by-products in the rock that are consistent with ancient microbes living off iron, sulphur and possibly also carbon dioxide and light through a form of photosynthesis not involving oxygen.

These new findings, according to the researchers, suggest that a variety of microbial life may have existed on primordial Earth, potentially as little as 300 million years after the planet formed.

Lead author Dr Dominic Papineau (UCL Earth Sciences, UCL London Centre for Nanotechnology, Centre for Planetary Sciences and China University of Geosciences) said: “Using many different lines of evidence, our study strongly suggests a number of different types of bacteria existed on Earth between 3.75 and 4.28 billion years ago.”

“This means life could have begun as little as 300 million years after Earth formed. In geological terms, this is quick – about one spin of the Sun around the galaxy.”

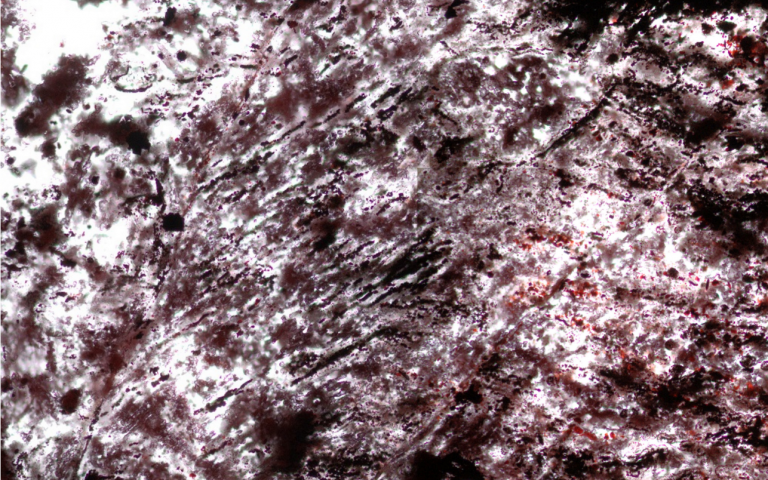

The research team sliced the rock into sections about as thick as paper (100 microns) in order to closely observe the tiny fossil-like structures, which are made of haematite, a form of iron oxide or rust, and encased in quartz. These slices of rock, cut with a diamond-encrusted saw, were more than twice as thick as earlier sections the researchers had cut, allowing the team to see larger haematite structures in them.

They compared the structures and compositions to more recent fossils as well as to iron-oxidising bacteria located near hydrothermal vent systems today. They found modern-day equivalents to the twisting filaments, parallel branching structures and distorted spheres (irregular ellipsoids), for instance close to the Loihi undersea volcano near Hawaii, as well as other vent systems in the Arctic and Indian oceans.

As well as analysing the rock specimens under various optical and Raman microscopes (which measure the scattering of light), the research team also digitally recreated sections of the rock using a supercomputer that processed thousands of images from two high resolution imaging techniques. The first technique was micro-CT, or microtomography, which uses X-rays to look at the haematite inside the rocks. The second was focused ion beam, which shaves away miniscule - 200 nanometre-thick - slices of rock, with an integrated electron microscope taking an image in-between each slice.

Both techniques produced stacks of images used to create 3D models of different targets. The 3D models then allowed the researchers to confirm the haematite filaments were wavy and twisted, and contained organic carbon, which are characteristics shared with modern-day iron-eating microbes.

In their analysis, the team concluded that the haematite structures could not have been created through the squeezing and heating of the rock (metamorphism) over billions of years, pointing out that the structures appeared to be better preserved in finer quartz (less affected by metamorphism) than in the coarser quartz (which has undergone more metamorphism).

The researchers also looked at the levels of rare earth elements in the fossil-laden rock, finding that they had the same levels as other ancient rock specimens. This confirmed that the seafloor deposits were as old as the surrounding volcanic rocks, and not younger imposter infiltrations as some have proposed.

Prior to this discovery, the oldest fossils previously reported were found in Western Australia and dated at 3.46 billion years old, although some scientists have also contested their status as fossils, arguing they are non-biological in origin.

Prior to this discovery, the oldest fossils previously reported were found in Western Australia and dated at 3.46 billion years old, although some scientists have also contested their status as fossils, arguing they are non-biological in origin.

The new study involved researchers from UCL Earth Sciences, UCL Chemical Engineering UCL London Centre for Nanotechnology, and the Centre for Planetary Sciences at UCL and Birkbeck College London, as well as from the U.S. Geological Survey, the Memorial University of Newfoundland in Canada, the Carnegie Institution for Science, the University of Leeds, and the China University of Geoscience in Wuhan.

The research received support from UCL, Carnegie of Canada, Carnegie Institution for Science, the China University of Geoscience in Wuhan, the National Science Foundation of China, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and the 111 project of China.

Links

- Research paper in Science Advances

- Research paper in Nature

- Dr Dominic Papineau’s academic profile

- UCL Earth Sciences

- UCL Mathematical & Physical Sciences

- UCL Chemical Engineering

- UCL Engineering

- London Centre for Nanotechnology at UCL

- Centre for Planetary Sciences at UCL/Birkbeck

Images

- Top. Centimetre-size pectinate-branching and parallel-aligned filaments composed of red haematite, some with twists, tubes and different kinds of haematite spheroids. These are the oldest microfossils on Earth, who lived on the sea-floor near hydrothermal vents, and they metabolised iron, sulfur and carbon dioxide. Nuvvuagittuq Supracrustal Belt, Québec, Canada. Credit: D. Papineau.

- Video. Credit: UCL / FILMBRIGHT

- Middle. Layer-deflecting bright red concretion of haematitic chert (an iron-rich and silica-rich rock), which contains tubular and filamentous microfossils. This co-called jasper is in contact with a dark green volcanic rock in the top right and represent hydrothermal vent precipitates on the seafloor. Nuvvuagittuq Supracrustal Belt, Québec, Canada. Canadian quarter for scale. Credit: D. Papineau.

- Bottom. Dr Papineau in the field. Credit: D. Papineau

Media contact

Mark Greaves

T: +44 (0)7990 675947

E: m.greaves [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close