How blind people can have visual hallucinations

8 January 2021

Visual hallucinations in people who have lost their sight can stem from spontaneous activity in the brain’s visual centres, according to a study led by UCL and Weizmann Institute of Science researchers.

The study, published in Brain, investigated why some people who have lost their eyesight experience vivid hallucinations, a condition called Charles Bonnet syndrome.

The researchers were studying slow, spontaneous fluctuations, which appear unconsciously in our brains when we rest. The research team was seeking to understand whether unprompted behaviours, that occur without any external cause, might be triggered by these spontaneous brain fluctuations.

People experiencing Charles Bonnet visual hallucinations presented the research team with a rare opportunity to investigate their hypothesis. This is because in Charles Bonnet syndrome, the hallucinations appear at random, in a truly unprompted fashion, and the visual centres of the brain do not process outside stimuli (because these individuals are blind), and are thus activated spontaneously.

The researchers first invited to their lab five people who had lost their sight and reported occasionally experiencing clear visual hallucinations. These participants’ brain activity was measured using an fMRI scanner while they described their hallucinations as they occurred.

The scientists then created movies based on the participants’ verbal descriptions, and they showed these movies to a sighted control group, also inside an fMRI scanner. Another control group, consisting of blind people who had lost their sight but did not experience visual hallucinations, was asked to imagine similar visual images while in the scanner.

The same visual areas in the brain were active in all three groups – those that hallucinated, those that watched the films and those creating imagery in their minds’ eye.

But the researchers noted a difference in the timing of the neural activity between these groups. In both the sighted participants and those in the imagery group, the activity took place in response either to visual input or to the instructions set in the task. But in the group with Charles Bonnet syndrome, the scientists observed a gradually increasing wave of activity, reminiscent of the slow spontaneous fluctuations, that emerged just before the onset of the hallucinations. In other words, the hallucinations were not the result of external stimuli (such as sensory images or instructions from the research team), but were instead evoked internally by the slow, spontaneous, brain activity fluctuations.

Lead author Dr Avital Hahamy (Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology), who began the study while based at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel, said: “Our findings have clinical significance, in helping us to understand Charles Bonnet syndrome, but they also teach us that spontaneous brain activity has a functional role in evoking unprompted perceptual behaviour – for example, the same spontaneous fluctuations in the brain’s visual centres may underlie dreams.”

In addition to the scientific value of the work, Dr Hahamy hopes it may raise awareness of Charles Bonnet syndrome, which can be frightening to those who experience it.

“These individuals may keep their visual hallucinations a secret – even from doctors and family – and we want them to understand that these visions are a natural product of a healthy brain, in which the visual centres remain intact, even if the eyes have ceased to send them sensory input,” she said.

Senior author Professor Rafael Malach (Weizmann Institute of Science) said: “Our research clearly shows that the same visual system is active when we see the world outside of us, when we imagine it, when we hallucinate, and probably also when we dream. It also exemplifies the creative power of vision and the contribution of spontaneous brain activity to unprompted and creative behaviours.”

Dr Hahamy’s research is supported by the European Molecular Biology Organization, the Human Frontier Science Program, and the the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme.

Links

- Research paper in Brain

- Dr Avital Hahamy’s academic profile

- Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging at UCL

- Weizmann Institute of Science press release

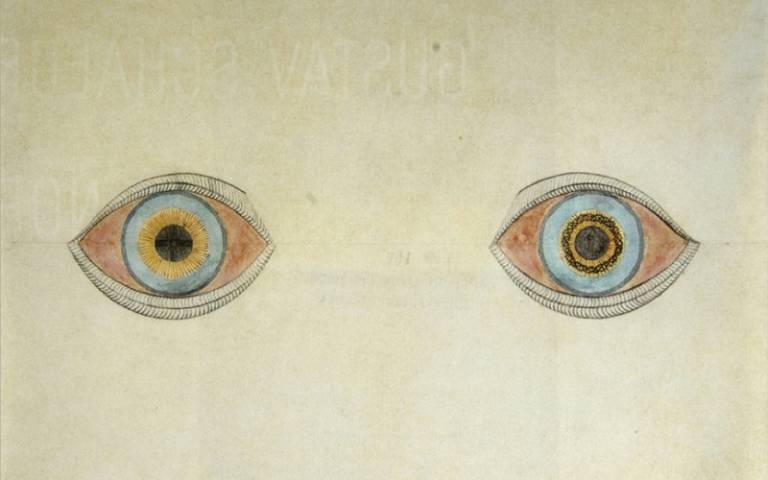

Image

- My Eyes at the Moment of the Apparitions by German artist August Natterer (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Close

Close