|

|

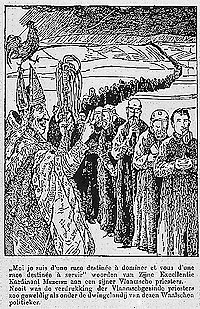

Catholic FlamingantismIntroduction “Moi je suis d’une race destinée...”, caricature on Cardinal Mercier (1906). >To read the caption in English translation please click here. >To enlarge the image please click here. In the 1900s the Flemish Movement campaigned especially for two matters: (1) for legislation forcing private Catholic secondary education in is entirety, both in Flanders and in Brussels, to switch to bilingualism – being private institutions, Catholic secondaries had until then escaped the provisions of the language law of 1883; and (2) for the conversion of the State University of Gent into Belgium´s first Dutch-language university. Reference has already been made to how these and other language laws were held off as a result of growing and better organized resistance on the part of French-speakers. The Catholic government put the brakes on any legislation laying the language regime in Catholic secondary schools. And the management of Catholic schools, the bishops in particular, flatly rejected any such legislation – in their eyes, Dutch was simply not a suitable language of instruction in secondaries, let alone at university. The illustration shown here is a caricature depicting the hostility of the Church hierarchy and Cardinal Désiré Mercier in particular vis-à-vis the Flemish Movement. The image shows muzzled pro-Flemish priests walking in a file in front of Mercier, who wears a mitre topped with a Walloon cock. Not only priests but Catholic politicians as well were expected to respond to the instructions of the bishops in this matter – one should note that the episcopacy played a significant guiding role within the Catholic party. For supporters of the Flemish Movement, Mercier defended the position of power and privileged status of French-speakers in Belgium. The Walloon cock was the symbol of the so-called Walloon Movement, in origin a movement fighting to safeguard the privileges of (exclusively French-speaking) Walloon officials and office-workers in Flanders and Brussels. Fragment“To my knowledge, our language movement cannot be compared with any other nationalist movement even though we naturally feel at one with all volated peoples who demand their rights. […] For our alienation is not of the same order as that of the Polish, the Irish, the Boers, the Croats and others; the strength of these foreign peoples as opposed to the life of our nation is not contained in external means of coercion, our weakness does not lie in the lack of outside support, but our powerlessness results from the inner degeneracy of our nation´s soul. Our people has lost almost everything, including its national consciousness, for the ideas of greatness and the sense of honour, the humiliation and wrongs which fire other nations, pass over our heads like shadows with neither weight nor substance. This is why the Flemish struggle must be an inner, spiritual struggle; the revival of our nation must come about through the renewal of our hearts and minds; our future greatness must burst forth with its own beauty from the intensive development of our many-sided creative force. A nation´s safest stronghold is self-respect and its most blessed posession, belief in its own strength, faith in its self-advancement. Therefore let all of us who desire that our nation should change restore that self-respect and that faith in ourselves and communicate it to our envirvonment through persuasion and education, through the burgeoning of our ever more powerful arts and sciences, through the elegance of our words, through all our public actions. We must reach everyone, the people from the humble houses and the educated. […] This way salvation lies, and only this way. […] If we, Flemish activists, have regained a national consciousness and a national will […], we will soon have won all the victories which must confirm that we have right on our side. Political agitation cannot help us either, if we have not already conquered the unhealthy passivity in our people.” Ingredients for a stronger Flemish consciousnessLike Vermeylen, van Cauwelaert identified in the Flemish people a certain passiveness, an indifference, a lack of Flemish consciousness; “we, the Flemish people, are our own enemy”, he wrote elsewhere. Extremely illuminating is van Cauwelaert´s reference to other nationalist movements and the possible role of “external means of coercion” in their success. Most historians agree that the Flemish Movement was unlike comparable movements. In contrast with, for instance, Polish or Irish nationalism, the Flemish Movement did not work for the restoration of an independence lost since long – “Flanders” was no age-old nation but the creation of the Flemish Movement – and, whilst nationalism in Poland and Ireland was linked to and bolstered by a political struggle for democratic state institutions, Belgium was already endowed with a constitution that was ahead of its time in 1830. For van Cauwelaert, the Catholic student movement was the motor of the Flemish Movement. As Flemish activists of the future, the priority of Catholic students should be self-education, that is, to make oneself fully conversant with the Dutch language and contribute personally to Flemish education and Flemish scientific, artistic and literary life with the aim of becoming more aware of one´s Flemish and Catholic identities – van Cauwelaert was as much a convinced Catholic as he was a declared supporter of the Flemish Movement. Only if its vanguard instilled into the masses respect for Flemish language and culture, would the Flemish Movement become a popular movement, van Cauwelaert argued. His instruction to Catholic Flamingants was therefore to commit themselves to the new social organizations of the Catholic pillar (trade unions, mutual-aid societies, farmers´ guilds, and so on). The interconnectedness between Catholic Flamingants and Flemish Christian-Democratic and farmers´ organizations would provide the Flemish Movement with a mass base after the First World War. Once again, this osmosis was to reinforce the Flemish Movement´s overwhelmingly Catholic image. At the root of van Cauwelaert’s argument was a profound sense of frustration about the lack of progress with regard to language legislation. The disapproval Vermeylen expressed to the Flemish Movement for having become too dependent on legislation and on struggling within the confines of Parliament, is echoed by van Cauwelaert who criticizes Flemish activists for begging and depending on “official benevolence”. The stagnation on the legislative front is, of course, also related to a radical qualitative jump forward in the Flemish Movement´s position on language legislation, which has been mentioned a few times. Now we want to expand on it some more. Territorial monolingualism for Flanders“Behind our backs they are saying that we are unbearable because we complain, troublemakers because we make demands, ungrateful because we do not declare ourselves satisfied with a meagre handout”, van Cauwelaert said. Now the Flemish Movement opted without hesitation for an official status of monolingualism for Flanders – all educational institutions, public administrations and law courts in Flanders were to be run exclusively in Dutch. Between 1906 and 1909 the Catholic government of the day was still experimenting with the idea of universal bilingualism. This idea implied the existence of bilingual officials and bilingual public services not only in Flanders (as was often still the case), but also at the national level and in Wallonia – in a sense, the Equality Law of 1898 provided a first taste of the notion of national bilingualism. However, Walloon politicians rejected this notion. As far as Wallonia is concerned, they claimed, people have to adapt to the language of the region where they live (i.e. in Wallonia French-language education and French-language public services only). What Walloon politicans defended, was the so-called principle of territorial integrity. The Flemish Movement concluded that if a monolingual status is acceptable for Wallonia, Flanders should be entitled to a corresponding status. Epilogue “Vlaamse en Waalse regimenten, anders niets!!”, print on the subject of army reform. >For the caption in English translation please click here. >To enlarge the print please click here. One of the last major language laws to be considered by Parliament before 1914, concerned the army. As a national institution, the army performed a key function in the process of nation-building. It was a vehicle for educating the common people to become Belgians. What this process of education included, was to instil the idea of French as the common language of all Belgians. The army, one has to remember, was and remained a solidly and exclusively French-speaking institution. Claiming for Flanders the principle of territorial monolingualism, Flemish activists now started to demand the splitting of the army into homogenously monolingual units – the army should be made up of Flemish and Walloon regiments. The illustration shown here expresses the sentiment of many Flemish militants. It portrays a Flemish Lion unwilling to be buttered up by any language law that did not fully meet the demand for Flemish and Walloon regiments. The caption tells us that in claiming this language right Flamingants still appealed to a sense of Belgian patriotism; Belgium was seen as a nation composed of two peoples, two sub-nations bound together by political, social and economic ties (“a fellow people” [57]). Granting Flemings and Walloons equal opportunities and equal rights contributes to Belgian prosperity and Belgian unity. So: no oppression of one people by another; and no imposing of the language of one people on the territory of another people (“that malicious yoke”). Whether it was because of lack of courage – as Vermeylen argued – or for the sake of >political convenience, most supporters of the Flemish Movement continued to subscribe to the Belgian unitary state. As was to be expected, establishing monolingual army regiments proved to be unattainable. For, the unity of the country was at stake, opponents claimed. The law that was passed in 1913 held out a prospect of a bilingual army command. In future officers and non-commissioned officers would have to be fluent in both national languages and would have to use both French and Dutch as language of command. Meanwhile the army remained in essence a French-speaking institution. A few Flemish militants now started to consider the option of self-government, an idea that had been launched in 1912 not in Flemish but in Walloon circles, by left-wing, freethinking supporters of the Walloon Movement, very much for fear of their region being permanently ruled by ´clerical´ Flemings. Their fear was understandable given that the Catholic party had now been in power for almost thirty years without interruption. Yet, only the shock of the First World War was to create an anti-Belgian Flamingantism, albeit supported still only by a minority within the Flemish Movement. One can argue that this was a genuine Flemish nationalism because for the first time it would claim political autonomy, Flanders no longer being seen as a sub-nation of Belgium but as a fully fledged nation in its own right. Decisive factors in this transformation were the accumulated feelings of frustration and impatience with the Belgian government and the interaction between Flemish militants and the German occupying regime (collaboration of the ‘>activists’; >Front Movement). Reading comprehension questions1. Why is the notion that Flanders is an age-old nation incorrect?2. What did the Walloon Movement stand for?3. Why were the mid-1900s a turning-point for Catholic Flamingants?4. Why were Flemish militants disappointed and frustrated about the outcome of their campaign for the use of Dutch in the army?5. Was total Dutchification of public life in Flanders the only remedy on the table to deal with Belgium´s linguistic problems? |