|

|

On the Political StageIntroduction

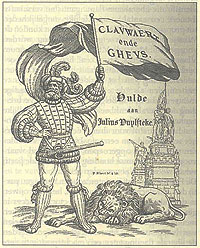

Around 1860 a second phase starts in the history of the Flemish Movement. By means of better organisation, campaigning and involvement in the press and in elections Flamingant militants tried to acquire political power themselves in order to redress their linguistic grievances. This change of strategy is related to a measured extension of the franchise, designed to include the petty bourgeoisie, against the background of the wave of revolutions sweeping across Europe in 1848. The Flemish petty bourgeoisie – still predominantly Dutch-speaking – continued to be the social base of the Flemish Movement, a movement that was now starting to gain political clout. At the outset the political activists representing this new electorate (Flamingants, progressive democrats,...) experimented with the idea of an all-inclusive “third party” in Belgium´s political landscape, a party independent from and in opposition to the established, upper-middle class parties, the Catholic and Liberal parties. Julius Vuylsteke, one of the most prominent Flamingant figures in this period, did not have any faith in such political experiments. In his opinion Flemish activists had to commit themselves to and exert pressure on the Liberal party. >If you want to read a short biographical note on Julius Vuylsteke, please click here. The “Flemish Question” is also a social questionAccording to Julius Vuylsteke (Gent, 1836-1903), barrister, politician, publicist and leading figure of the Willems Foundation – a Flamingant cultural association – the “Flemish Question” was more than just a language question: it was a social question. Behind the linguistic grievances there was material misery and intellectual deprivation, which were holding up the reawakening of the ´Flemish people´. Vuylsteke set forth his ideas in his Brief Statistical Description of Belgium (Gent, 1865-69), of which we have selected three extracts. In his opinion Flanders ranked below Wallonia in the areas of education, literacy, wage levels, employment (see fragment 1), industrialization, nutrition, public health, life expectancy, population growth, serious crime and political consciousness. The image he projects in the first fragment is that of “>poor Flanders”, a region which in the mid-19th century was declining very sharply, not only in comparison with its rich past but also compared to industrializing Wallonia. The result was that the negative perception of Flemish – the language of “poor Flanders” – was further reinforced. Speaking Flemish came to be associated with poverty and intellectual backwardness. The second extract shows Vuylsteke as a representative of the progressive democratic opposition movement, on the up in the 1850s and 1860s. Fragment 1“It is the fruits of education which set the seal on the work. In the province of East Flanders the level of basic learning (forgive the word) is appaling; in 1866, 34 out of every 100 >conscripts were totally illiterate. While the other Flemish provinces may not be quite as bad, overall they still lag behind the Walloon provinces, a couple of which yield figures – splendid ones for our country – of only 5 to 13 illiterates per 100! [...] Daily wages are in general noticeably lower in the Flemish provinces than in the Walloon provinces. In agriculture there is a difference of between 20 to 50 per cent. Moreover, wages are rising fairly rapidly among the Walloons, while among the Flemings they are almost static. And Professor E. De Laveleye, in his book Agriculture in Belgium, comes to the discouraging conclusion that, of all European workers, the day-labourer in the Flemish provinces is possibly the one who works hardest and is the worst nourished! Statistics on Poor Relief confirm this important truth. Of every 100 inhabitants in the Flemish areas, more than 17 were charges on the >Board of Guardians, in the Walloon areas only 11 [...]. Things are much worse than this in some areas. In Bruges in 1863, out of a population of just under 50,000 there were 17,786 persons receiving relief from the Board of Guardians; that is to say, 36 out of every hundred.” Fragment 2“The saddest phenomenon, however, is this: while it is clear that Flanders has the most serious lack of education, of good schools, of good school premises, it is also there that the least is being done to remedy this lack; and while in the Walloon area the municipalities, provinces and the State combined have spent 12 million francs in the last five years on extraordinary works for primary education, in the Flemish area, where the need is so much greater, only half that sum was spent. [...] [T]he saddest thing is not the situation in itself, but the lack of initiative in contriving and introducing measures against it. Many practical methods lie already to our hands; but if you search our land for public baths and wash-houses, societies for building healthy working-class dwellings, savings banks, co-operative or retailers´ associations, cheap municipal kitchens, etc. – all means of alleviating the evil which already been tried and tested many times elsewhere – in the Flemish areas, with a few very rare exceptions, you will look in vain.” A progressive-democratic perspectiveFor Vuylsteke and many other progressive liberals and democratic Catholics from the ambitious lower middle classes, the fight for the Dutch language was part of a broad programme of democratic reform directed against the Establishment of the 1850s and 1860s. Although each emphasized their own points, most wanted >linguistic Flamingantism to go hand in hand with the improvement and expansion of education, a broader franchise, economic development and prudent social policies (see fragment 2). In the opinion of Vuylsteke, inspired by his Liberalism and his belief in the ideals of the >Enlightenment, the source of “poor Flanders´” backwardness was the intellectual inferiority of its lower classes. The resulting emphasis on education in particular will be reflected in the central position education is given in the programme of the Flemish Movement down to 1914. For Vuylsteke, the struggle of Flamingants corresponded with the fight fought by Liberals. Early on he came to the conclusion that the antagonism between Liberals and Catholics overrode all other political disputes – making a large contribution himself to the Liberal-Catholic conflict – and he did his utmost to bring the supporters of the alliance between Flemish activists and progressive democrats into the orbit of the Liberal party. In the next extract Vuylsteke explains why the Flemish cause and the Liberal cause are one and the same. Fragment 3Enlightenmentliberty – equality – civilization – free enterprise – belief in progress – belief in the perfectibility of man and society “The conclusion is that since the sixteenth century the Dutch-speaking population (literally: the Dutch population) of Belgium has lived constantly under influences which could not but lead to degeneration, enfeeblement and decline; and that to such an extent that it is not surprising that distressing symptoms are now appearing. What is surprising is that the situation is not far worse. History confirms that the evil revealed by the statistics must be ascribed on the one hand to the unnatural and antisocial isolation of the population from intellectual contact with the higher classes and the culture of the Northern Netherlands, and on the other hand to the ignorance fostered by an intolerant priesthood, with its consequent narrow-mindedness, fanaticism and prejudice. There you have the two principal causes of the evil. He who does not fight both of them at the same time is doing only half the job. We cannot say that his view is wrong, but he does not see everything, he sees only half the truth. There are those who anticipate an instant and total recovery simply from the restoration of our natural language, and others who reserve their rancour for the ´>theocracy´ and who, far from desiring a revival of the Dutch language, lay on it the blame which belongs solely to those who neglected it and permitted it to be neglected. Both groups are clearly in error.” Flamingantism hopelessly divided by Liberal – Catholic party-strife “Clauwaert ende Gheus”, in honour of Julius Vuylsteke. >To enlarge the illustration please click here The above extract shows how Vuylsteke attributed the Flemish people´s material misery and intellectual inferiority partly to the neglect of Dutch, partly to ´theocracy´, as he called it. Church and clergy were accused of subjecting the people to a regime of ignorance and superstition. Therefore, the resurgence of the Flemish people had to be coupled with all-out war against the Church. Vuylsteke and like-minded figures – who, unlike previous generations of Liberals, openly married their liberal ideas with >freethinking and >anticlericalism – believed that co-operation with Catholics, even concerning the Flemish Question, was inadmissible. Vuylsteke was actually one of the figures who helped instill a more aggressive anticlericalism in the Liberal party. Yet what makes him interesting is the fact that he did so by writing the Flamingants´ fight into an age-old history (according to the third fragment, “since the sixteenth century”) of Flemings struggling against clerical claims and against Frenchification. These ideas are encapsulated in the slogan “Klauwaard en Geus”, which is the subject of the illustration. The symbolism of the “>geuzen” or Beggars – the figure of the “>klauwaard” will be looked at below – was popularized in 1872 by the tercentenary (celebrated in the Netherlands) of the >fall of Den Briel , a key moment in the >Revolt of the Netherlands against Spain. Liberals like Vuylsteke glorified the Beggars as the embodiment of the war against the Church – against “popery” – and of the restoration of the bond with the Netherlands (see below). On the one hand, Vuylsteke, the first great Liberal Flamingant, was able in this way to infuse a dose of Flamingantism into the Liberal party. Yet, on the other hand, his way of thinking left no scope for collaboration between supporters of the Flemish Movement belonging to different ideological communities (i.e. Catholics and Liberals). By 1870 the >conflict over the position of the Church in public life dominated Belgian politics to such an extent that Flemish activists had sided with the Liberal or Catholic party; establishing a third (pro-Flemish, progressive-democratic) party turned out to be unrealistic. Adding to the odds against it was the Belgian electoral system (>majoritarian representation) which offered room for no more than two parties. The Flemish Movement ended up being hopelessly divided. “Restoration of our natural language”Key events in Flemish mythology11 juli 1302: Battle of the Golden Spurs Frenchification was the other principal cause of the evil denounced by Vuylsteke in this document (see fragment 3). For him and for the Flemish Movement as a whole, “restoration of our natural language” meant the official recognition in Flanders of the Dutch language, alongside French, in other words granting Flanders an official status of bilingualism. Making Dutch the only language of public life (or: total Dutchification) was not on the programme. The “restoration of our natural language” would entail the following developments. Firstly, it would benefit the contact between the Dutch-speaking population and Flanders´ largely Frenchified elite. The supposition was that more contact would help raise intellectual standards and the level of culture of the lower classes. The “klauwaard” referred to in the illustration was a symbol of the popular resistance against Frenchification and the Frenchified Flemish elite. In the era of the Battle of the Golden Spurs (1302) the “klauwaards”, named after a “klauwende” or clawing Flemish lion, were the opponents of the French king and the pro-French urban elites of Flanders. Whilst Hendrik Conscience saw in the Battle of the Spurs firts and foremost een battle against France, later generations of Flamingants also viewed it as a fight against French influence in Flanders, a fight against the “internal enemy”: the Frenchified bourgeois. Secondly, Vuylsteke was convinced that closer contact with “the culture of the Northern Netherlands” would further the Flemish cause. Like Willems, Vuylsteke opposed the idea of an independent Flemish-Belgian language, different in spelling from the Dutch language – something Catholics supported, among other things, in order to ward off influences from Protestant Holland; instead, he advocated linguistic unity and more intellectual dialogue between the Netherlands and Flanders. This type of pro-Dutch disposition is a characteristic that one also finds in later generations of Liberal Flamingants. >>First language lawsIn the 1870s campaigning, press endeavours and political pressure started to bear fruit. Language laws passed in 1873, 1878 and 1883 (on criminal justice, the civil service and state-run secondary education respectively) recognized Dutch as an official language, alongside French, in the Flemish part of the country. Dutch-speakers gained a number of elementary rights such as the right to be tried in one´s own language; the right to be attended to by civil servants in one´s own language; and the right to be educated in state secondary schools at least in part through the medium of one´s own language (instead of exclusively through the medium of French). However, this legislation still guaranteed the French language a place in the justice system, in the civil service and other public administrations, and in education in Flanders; moreover, French remained the ´national language´. Flanders was on the road to a bilingual status, no more, no less. If you want check out an overview of language legislation, please go to “Chronology”. The Catholic party was preferred choice of one part of the Flamingant electorate. They did so partly because Vuylsteke´s cherished Liberal party was too anticlerical, partly because the Catholic party was more receptive to Flemish linguistic demands – both the 1873 language law and the 1878 law were passed under Catholic governments. The Flemish Movement of these years was to fall more and more into the Catholic orbit and in time relied increasingly on an internal pressure group within the Catholic party. Catholics, just as much as Vuylsteke, used the Flemish Question as ammunition in the political battle between Liberals and Catholics. They did so by propagating, more than ever before, the idea of “Catholic Flanders”, a conservative people devoted to religion, the mother-tongue and ancestral morals; in other words, the antipode of what Vuylsteke imagined Flanders to be: a nation of anticlerical, pro-Dutch Beggars. >Guido Gezelle, priest, teacher and advocate of the use of dialect as the basis of the written language, is the most influential literary exponent of this traditionalist Flamingant position. This is one of the reasons why Flemish Liberals (joined in this respect by Flemish Socialists later on) were to be increasingly distrustful of a movement which they perceived as ´clerical´. Another reason was that the Flemish Movement´s programme did not move on beyond language demands; only in the 1890s, three decades after the attempt of democrats such as Vuylsteke, were new efforts made to broaden the programme. Reading comprehension questions1. Why did Vuylsteke disagree with those who in fighting for the resurgence of the ´Flemish people´ pinned their faith entirely on language laws?2. Which social group championed the cause of the Flemish Movement and do you think Vuylsteke´s diagnosis if the Flemish Question and the remedies proposed altered the movement´s support base in some way?3. Why was the Flemish Movement internally hopelessly divided?4. Vuylsteke painted a view of Flemish history with an unmistakable Liberal hue. The motto “Klauwaard en Geus” harked back to events surrounding the Battle of the Golden Spurs and the Revolt against Spain. Why do you think the Revolt was such a rich source of inspiration for Liberal Flamingants?5. In the third extract Vuylsteke vented his criticism, among other things, against fellow-Liberals who “far from desiring a revival of the Dutch language, lay on it the blame [of the decline of the Dutch-speaking population].” What does this reference suggest to you regarding the perception of the Dutch language among part of the Liberal party?6. Did the linguistic grievances of Vuylsteke´s generation differ from those which the 1840 petition publicized?7. In the first paragraph of the third extract, Vuylsteke uses the term “the Dutch population of Belgium”. Why would he have chosen this term?>To find out more about the momentum of change in the 1890s please click here. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||