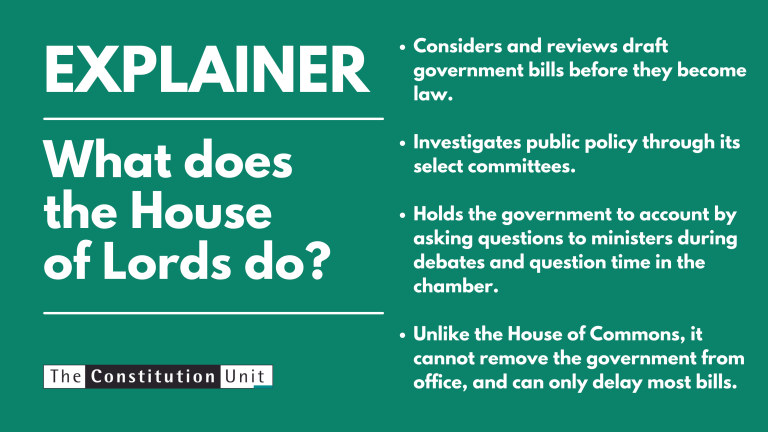

The House of Lords has three main functions: making laws, investigating public policy and holding the government to account. The House of Lords is the less powerful partner in the Westminster parliamentary system: unlike the House of Commons, it cannot remove the government from office and it can only delay, rather than veto, most bills.

The House of Lords once was more powerful than the House of Commons. Up to the passing of the Parliament Act 1911, the House of Lords held the power to veto bills passed by the House of Commons. The 1911 Act saw this power reduced to the delaying power the House of Lords has today – this was one of the most radical reforms to the House of Lords in its history.

Members of the House of Lords spend a lot of their time considering draft government bills before they become law. However, any proposed amendments to legislation must also be agreed by the House of Commons. Its primary function is therefore as a 'revising' chamber, asking the House of Commons to reconsider its plans.

Through the work of parliamentary select committees, peers investigate public policy covering a wide range of public policy, from justice and home affairs, to the long-term sustainability of the NHS. Committees produce reports which can often directly or indirectly influence the formulation of government policy.

Holding the government to account is another function of the House of Lords. During question time and debates in the chamber members put questions to government ministers who must respond.

It is very rare for peers to try to overrule legislation passed by the House of Commons as a whole. Under the Salisbury Convention the House of Lords does not try to block bills that were promised in the governing party’s manifesto and rarely blocks any bill in its entirety. In general, the unelected House of Lords defers to the House of Commons’ democratic mandate, but makes proposals for MPs to think again.

As it does not hold a majority, the government is defeated in the House of Lords quite often, generally on amendments to bills. Constitution Unit research shows that in recent years just under half of defeats have gone on to be accepted by the House of Commons, leaving a lasting impact on policy. A high-profile example under the Labour government occurred in 2006, when the House of Lords repeatedly voted against compulsory ID cards. The government chose to delay the implementation of ID cards until after the 2010 election. That election resulted in a Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government, which went on to scrap ID cards. This episode was highly adversarial, but more commonly members of the House of Lords propose changes which the government accepts, in order to improve the substance of legislation.

The House of Lords is equipped to perform this ‘revising’ role due to the wide range of expertise and experiences of its members, and its independence of thought — a large proportion of its members have no political affiliation. Some members are former politicians, while others are expert in business, education, science and other public policy areas. Of the around 800 members, most have been appointed as 'life peers' by the monarch on advice of consecutive prime minsters; the rest comprise 92 hereditary peers and 26 Church of England Archbishops and Bishops.

Many call for reform of the House of Lords, primarily due to it not being elected by popular vote. There are many options for reform but history demonstrates how tricky reform is. It is widely argued that one of the most urgent reforms needed is to contain the ballooning size of the House of Lords by restricting the Prime Minister’s power to appoint new peers.

Close

Close