The 1.5˚C Charter

In 2015, 196 heads of state and climate experts agreed in Paris to limit global heating to 1.5˚C, compared to pre-industrial levels. Why? Because exceeding 1.5˚C of warming puts life on earth as we know it at risk. Since then, we’ve heard a lot about how much it will cost to meet this goal, but should we be really talking about the cost of exceeding 1.5˚C?

Scientists from UCL, the University of Exeter and the International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD) have the launched the charter to highlight how breaching the 1.5˚C target will cost far more than paying poorer nations to help the global efforts to reach it.

- Why 1.5˚C?

Why is it so important to prevent more than a 1.5˚C global temperature? The climate is already changing; with a 1.5˚C average rise, places that are already hot will still experience extreme high temperatures. However, beyond a 1.5˚C change there will be so much heat globally to push many of the planet’s natural systems out of balance; a balance that could not be regained.

But this is not inevitable; for every 0.01 degrees of warming that can be prevented millions of people will be protected from death and displacement. The human benefit of capping global heating to 1.5˚C would be enormous, including:

- Saving $2.4 trillion for the global economy

- 500 million fewer people forced to leave their homes due to flooding (Lenton)

- 153 million fewer premature deaths from air pollution (Shindell)

- 1.7 billion fewer people exposed to severe heat waves every five years (IPCC)

- How can finance help us achieve 1.5˚C?

The aim of the charter is to act as a catalyst to encourage wealthy nations to supprt those less wealthy not only to decarbonise but also to ensure they can afford the adaptation measures to protect their homes, jobs and lands from climate related impacts like extreme weather, poor health, job losses and food insecurity.

The charter starts out by recognising that the human and economic costs of global heating far outweigh the costs of decarbonisation.

By developing climate finance mechanisms which link the cost of delayed action to the profits from those industries who are not decarbonising we could make the early investment in zero carbon infrastructure that is desperately needed.

We know that inequality drives global instability, investment in the resilience of the communities most at risk to the impacts of climate breakdown will also rapidly increase our ability to bring down carbon emissions and move things in the direction of ecological and economic equilibrium.

- Why now?

Five years on from when the 1.5˚C target was first agreed, 197 governments and organisations will meet to determine the future of our climate at what is known as the Conference of Parties or ‘COP’, a global United Nations climate change summit, in November 2021. COP26’s President Alok Sharma recently described the summit as the "last hope" for achieving 1.5˚C.

From the transition to clean energy, to the role of cities in achieving net zero, there are a range of crucial issues at stake. The Charter emphasises that the cost of failing the 1.5˚C target, and associated climate finance, must be on the agenda too.

- What does the charter call for?

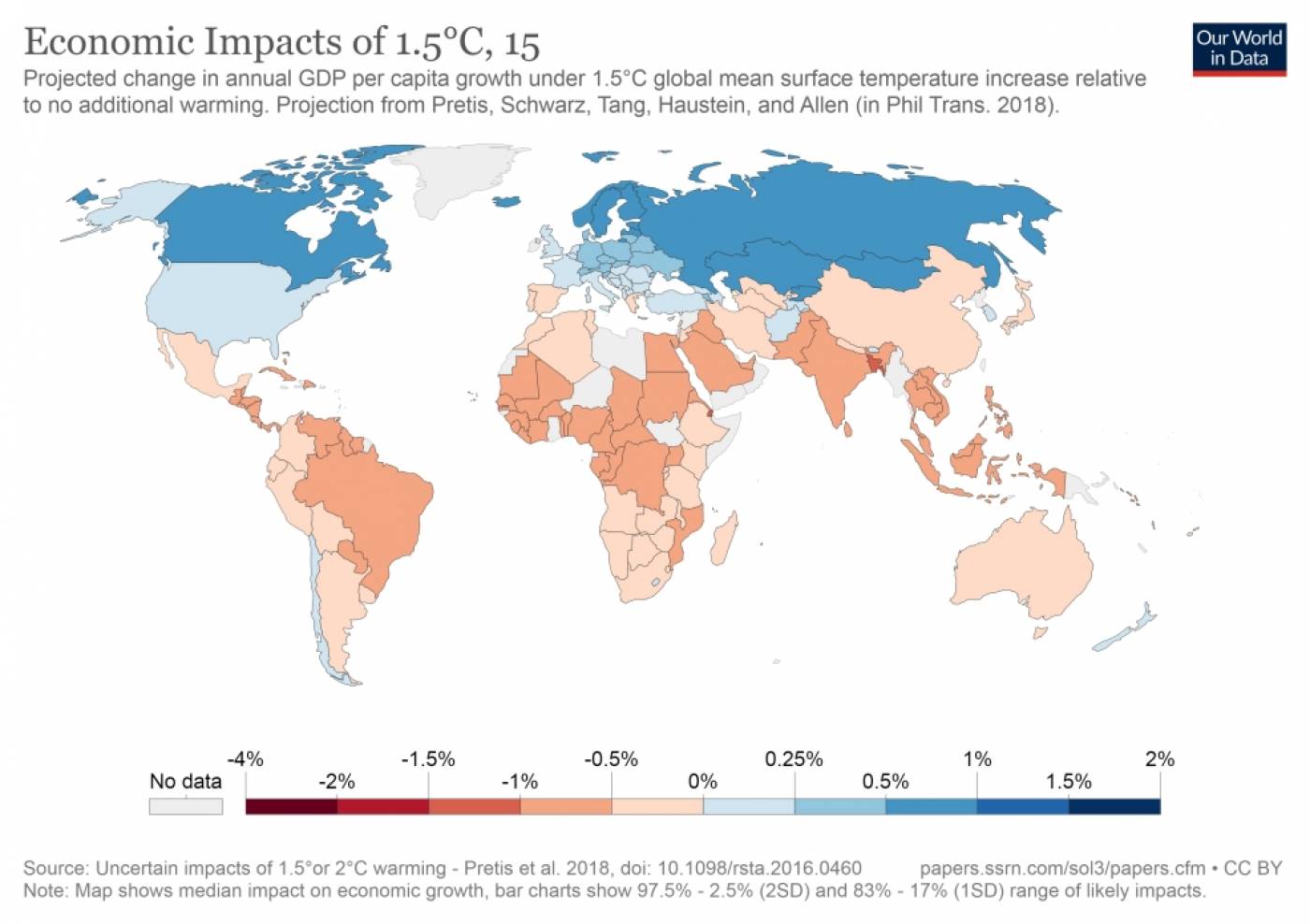

The cost of global warming

- The breach of 1.5˚C global warming comes with a cost; rising temperatures destroy the environment and livelihoods and destabilise economies

- This cost is a global cost;

The injustice of this cost

- This global cost is unequally distributed – both among current generations and future generations;

- This cost is incurred as a consequence of delayed action - and that action has been and continues to be delayed in defence of private profit; which is also unequally distributed;

Meeting the cost of global warming

- To meet the costs of rising global temperatures, mechanisms for appropriate climate finance should connect profits gained through delayed climate action to costs (and distribution of costs) incurred;

- Since global costs are anticipated to vastly outweigh profits made by delaying action, time-frames for transition to a carbon neutral economy should be urgently set within economically viable limits;

Addressing the injustice of the cost of global warming

- That transition, too, through its dependency on the ongoing extraction of natural resources and consequent displacements, comes with a distribution of cost and profit;

- This distribution, like the distribution of climate impacts, poses a long-term threat to ecological and economic stability across the planet;

- Moving forward, mechanisms for appropriate climate finance should recognise such potential impacts of transition and seek to advance processes of both mitigation and reparation from the outset.

Close

Close