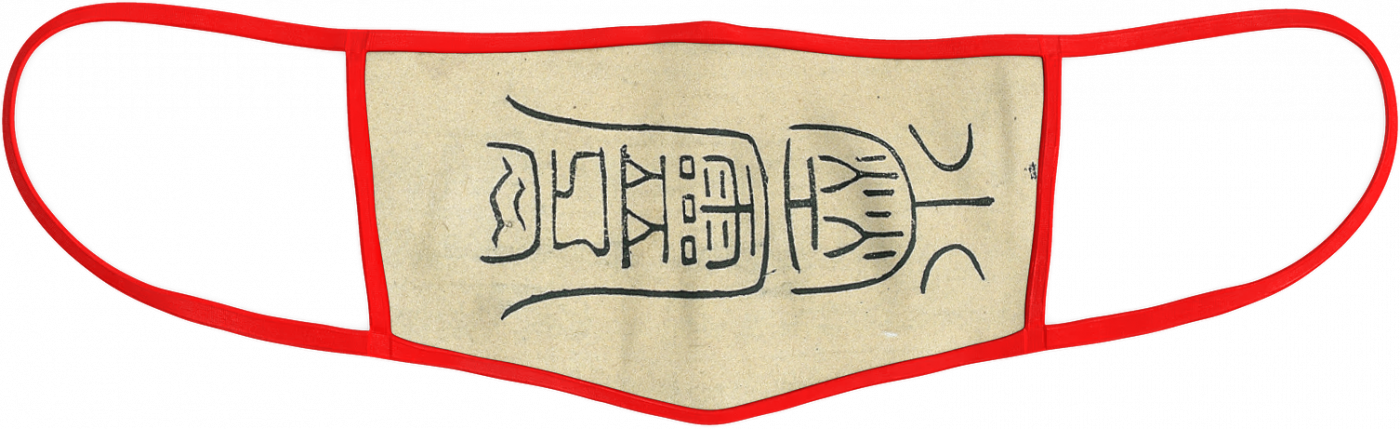

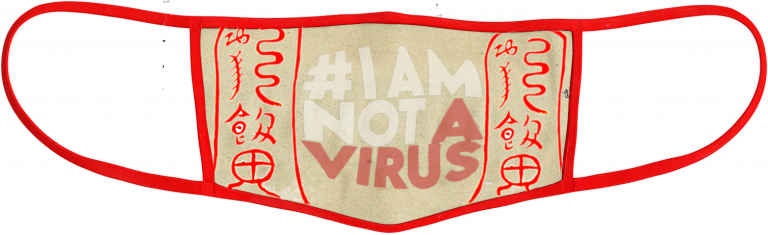

The talisman masks on these pages are part of the creative history practice of CCHH PhD candidate Luis Fernando Bernardi Junqueira

Religious healing and Covid-19

Amulets and Talismans

by Luis Fernando Bernardi Junqueira

Door amulets (menpai 門牌) have for centuries been used in China to ward off evil (bixie 辟邪) in all its physical and spiritual forms. The artefacts above illustrate the wide array of wooden door amulets that circulated in late imperial China, whose forms varied not only according to times and larger regions (for example, northern and southern China) but even from one village to the next. Their variations are expressed in the multiple names they are known by, including bagua shoupai 八卦獸牌 (beast tablet with eight trigrams),[1] bagua jianshipai 八卦劍獅牌 (lion-biting-sword tablet with eight trigrams)[2] or simply shoupai 獸牌 (beast amulet).[3] Both the amulets above are preserved in the Wellcome Collection at the Science Museum, but they continue to circulate widely amongst Chinese communities worldwide.

Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Christian missionaries recorded the pervasive use of household amulets among the Chinese, meant to drive away evil and avert epidemics.[4] Adam Grainger, a British missionary who lived in Chengdu from 1889 to 1921, listed some of these amulets – as well as the rationale behind them – in an article published in 1917:

A small mirror fixed above the door absorbs them [i.e., demons] into “Looking Glass-House.” A tablet, or mirror, in which is written “One Good” [一善] will foil their attempts because the proverb says, “One good deed annuls a hundred evil deeds.” [一善勝百惡] A tablet, or mirror, in which is drawn a conventional landscape [山海鏡], will allure them into bypass where they will be lost. A tablet of the Eight Diagrams quells all evil influences. A “Swallower” [吞口] or idol’s head, with a sword in its teeth, will slay them. This idol is the Daring One [敢當] of Mount Tai in Shantung who beheads demons. His head is sometimes painted on the back of a water-ladle, and sometimes carved out of a block of wood. The same figure is often carved on the top of a stone slab, on the front of which is written, “The Mount Tai stone Kan Tang,” which may also be translated, “The Mount Tai Stone dares to oppose.” [泰山石敢當] These stones are found in front of shops, public offices, cross roads, or river bends, and may be from three to ten feet high.[5]

Talismans (符) are artefacts composed of characters and symbols written in a certain fashion and used for healing or apotropaic purposes, including warding off plague demons like nüegui 瘧鬼 and yigui 疫鬼. They are typically drawn with cinnabar, black ink, herbal decoctions and even blood on strips of white or yellow paper, objects – like ritual vases or behind the amulets presented above – or directly onto the body. After being activated by mudras and verbal spells, talismans can be burned to ashes and mixed with water to be taken as a decoction, pasted on walls or carried about with the individual in order to avert any harm plague demons might cause. The talisman above (in red), used against wenyi 瘟疫, comes from a seventeenth-century manuscript held in the Library of Ancient Books at Fudan University.

Talismans can assume multiple forms and are not supposed to be read by humans; rather, they serve as a writ through which humans communicate with, or give commands to, the spirit world.[6] Recent archaeological discoveries have shown that talismans and spells–the verbal aspect of talismans–have been used in China for, at least, the past two millennia.[7] When the first Chinese imperial medical institutions emerged around the 6th century CE, talismans and spells were soon incorporated as an officially-sponsored medical discipline alongside drugs (herbs, animals and minerals) and massage, a status enjoyed until the late 16th century. Despite the fierce debates around the legitimacy of talismanic healing and its place vis-à-vis orthodox medical traditions, talismans and spells remained pervasive among both scholarly and folk healers in pre-Communist China, being hailed as one of the main treatments to cure or prevent epidemics.

[1] https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co122685/amuletic-board-china-1801-1900-amulet

[3] https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co125325/wooden-sign-painted-with-a-demons-face-china-shield

[4] Henri Doré, Researches into Chinese Superstitions, 13 vols (Shanghai: Túsewei Printing Press, 1916), vol. 3.

[5] Adam Grainger, “Various Superstitions,” West China Missionary News 19, no. 11 (1917): 10–16.

[6] Stephan P. Bumbacher, Empowered Writing: Exorcistic and Apotropaic Rituals in Medieval China (St. Petersburg: Three Pines Press, 2014).

[7] Donald Harper, Early Chinese Medical Literature: The Mawangdui Medical Manuscripts (New York: Routledge, 2015).

Close

Close