Cancer in a time of COVID – keeping vital research and treatment on track

4 February 2021

To mark World Cancer Day, we asked our scientists about how UCL has been able to continue vital cancer research throughout the pandemic. Cancer Institute Director, Tariq Enver, and clinician scientists, Adele Fielding and Gert Attard, share their thoughts

"We mustn’t give up on cancer – it certainly hasn’t given up on us," says Tariq Enver, Professor of Stem Cell Biology and Director of the UCL Cancer Institute.

Facing unprecedented disruption to funding streams, material resources and clinical capability, simply keeping the Paul O’Gorman Building – main site of the Institute – operational throughout the Covid-19 pandemic was far from easy. But doing so demonstrates UCL’s commitment to patients, and the world-leading and unique cancer research capacity that will impact so many of their lives.

In partnership with Cancer Research UK, the Institute is home to one of the largest cancer trials centres in the UK. Its critical role in tackling such a profound health issue makes it unthinkable that its work should stop for a year or longer.

Supporting cancer patients

“Through UCL Partners, we support around eight million patients, in a mixed area of London with immense under-privilege. We had to keep going so that patients could continue to receive the best and most advanced care, and so that we wouldn’t be starting from zero after the pandemic recedes. Cancer itself remains an ongoing pandemic – we cannot afford to slow down,” Professor Enver adds.

Professor Enver’s words are borne out of projections – released by UCL at the outset of the first lockdown – which suggest that there could be an additional 18,000 cancer deaths in England attributable to the effects of coronavirus.

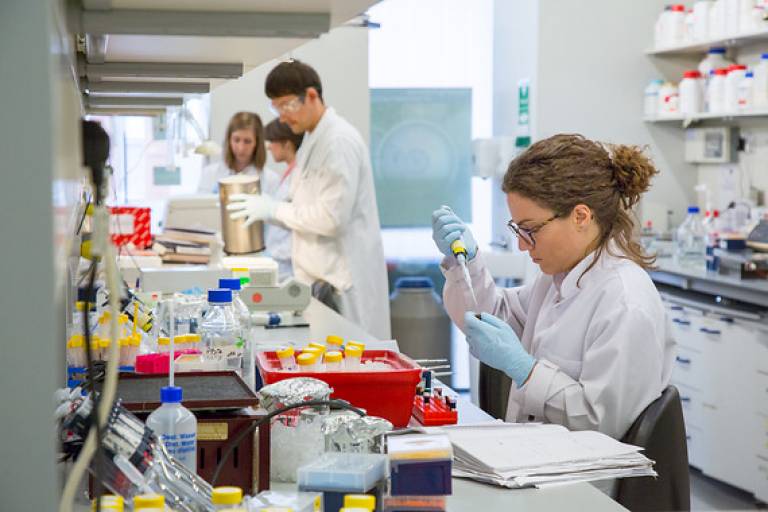

In response to such a stark outlook, researchers quickly adapted long-established ways of working so tasks such as computational research could be achieved from their homes. However, lab-based work had to take place at the Institute. With low occupancy strictly enforced in order to ensure social distancing, those on-site were able to maintain remarkable levels of productivity.

Continuing clinical trials

Urological cancer specialist Professor Gert Attard leads one of the teams that has kept its vital work going under national restrictions. His research into prostate cancer has identified a ‘fingerprint’ in the blood that provides an early signal that the disease is active and spreading, meaning doctors can assess how advanced a person’s cancer is and determine the best course of action.

Knowing how important the work is to clinical trial participants, he and his team were determined to continue processing the donated samples which would otherwise have been disposed of.

“Samples come to us from across the country,” Professor Attard says. “The flexibility and support of UCL made it safe and feasible for lab work to be done, and we kept going thanks to the extreme dedication of staff, who recognised patients’ wishes to be on the trial and didn’t want to waste their samples.What we managed was small compared to what we normally do, but it was important nonetheless.”

Professor Adele Fielding, one of the leads for the UK’s clinical trials programme for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, agrees that finding a way to continue was the right course of action.

Her lab receives specimens from across the UK for patient-specific tests to detect minimal residual disease – small numbers of leukaemia cells that remain in a person during or after treatment. Each test is unique to an individual’s tumour, and closing the lab would mean adult patients whose sample had been lodged with UCL would not get access to testing.

“We were driven by the realisation that, if our work stopped, there was no chance that these patients could be helped,” she says.

Working through a series of lockdowns is complex. The team needs to manage access to buildings when the majority of the campus is closed and ensure the safety of its personnel in the lab – but also to access reagents amidst a huge surge in global demand owing to COVID-19 testing programmes. As a result, one member of the lab was re-assigned to purchasing supplies on a full-time basis.

“It didn’t reduce the level of specimen testing we are able to do, but it was much more work to do it,” Professor Fielding says. “Despite the challenges, it is an absolute pleasure and gives the team an additional sense of purpose during a terrible time. I’m very proud of the lab for pulling together so effectively.”

Tackling Covid-19 through research innovation

As well as keeping its research up and running, the Cancer Institute has also found new ways to support UCL’s rapid contribution to the broader national effort against COVID-19 through testing and research; for example, tackling the issue of blood clotting that some coronavirus patients experience.

“We’re good at looking at blood,” says Professor Enver. “So we were able to apply our blood cancer expertise to one of the main effects of serious infection that made so many patients go on ventilation. Thanks to a state-of-the-art cell sorter – acquired through a philanthropic donation – we were able to work out why the immune system is causing these big problems.”

The Institute also diverted its antibody engineering expertise to COVID-19 research, drawing on two decades of innovation in developing antibodies to fight cancer. By creating a unique ‘cocktail’ of recombinant antibodies, this treatment could block the virus from entering cells and remove it from circulation – vitally important for cancer patients, who are often more vulnerable to COVID-19.

But whilst utilising its considerable knowledge to tackle the virus, UCL scientists have been proactive in raising awareness of how cancer research and treatment has been affected by lockdowns and the focus on COVID-19. UCL published its first analysis in April showing that the UK could see at least 20% more deaths over the following 12 months in people newly diagnosed – finding a 76% decrease in urgent referrals and a 60% decrease in chemotherapy appointments.

“Of course it is right to tackle COVID but cancer remains a major issue and the impact on patients will become evident over the next year,” says Professor Attard. “We’re in the process of rebuilding to get back to where we were and get momentum going again, but the reality is that research has been put back by months and patients have been hit badly by not being able to access their normal treatment.”

In addition, diminished funding for cancer research is a particular and urgent source of concern. Clinical trials are funded for a particular period, Professor Attard explains. “So when something stops for five months, where do you get that time back? Funders don’t have five months of extra funding to add on.”

“It’s a desperate situation,” says Professor Adele Fielding. “Charities are a huge mainstay of cancer research funding and the continuation of basic research relies on them. The impact will be felt everywhere, from research and clinical trials to training. “There could be long-term implications for this country’s life-saving research and translation capacity.”

Professor Enver shares his colleagues’ deep concern. However, he is determined not to lose the extraordinary momentum the Institute and the wider UCL community has built up prior to the pandemic.

“Now more than ever we need to keep this amazing show on the road,” he says. “We can move quickly for as long as we have the funding to do so. We are not giving up on cancer patients and we won’t let them be forgotten. Our vision and commitment hasn’t lessened; we are still researching, still treating, still striving.”

Further information

- Stem Cell Lab - Prof Tariq Enver

- Biology of Adult Lymphoblastic Leukaemia and Oncolytic Virus Therapy - Prof Adele Fielding

- Treatment Resistance Research Group - Prof Gert Attard

- World Cancer Day - UCL research spotlight

News: Insight into immune cell activation could help identify Covid-19 patients most at risk of pneumonia

Close

Close