At the International Society for Utilitarian Studies conference held in the German town of Karlsruhe, Prof. Emmanuelle de Champs presented some recent findings on Bentham’s contacts with Germany.

In the 1770s and 1780s, while he was drafting his first plans for a thorough reform of criminal legislation according to utilitarian principles, Bentham had his eyes set eastwards, especially on Frederick the Great’s Prussia.

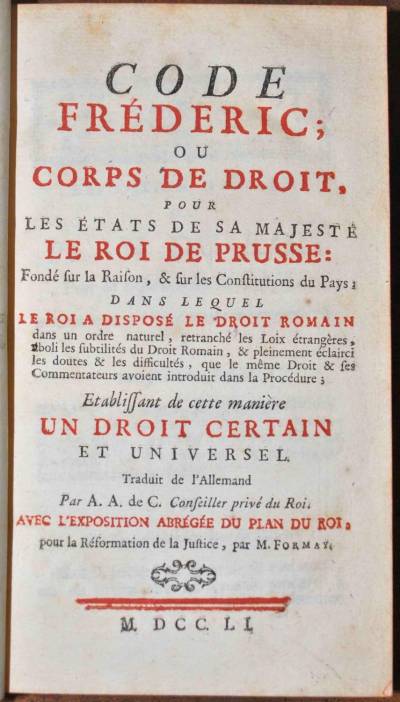

Frederick had launched major legal reforms in his kingdom. The first volume of the Frederician Code had been published in 1751 and had been praised by Diderot and d’Alembert, the editors of the Encyclopédie.

Naturally, Bentham thought of Frederick as one of the rulers to whom his plans could be directed. As early as the autumn of 1779, as his younger brother Samuel was passing through Prussia on his way to make his fortune in Russia, Bentham made plans for having his work on the Penal Code translated into German by Rudolf Eric Raspe – a literary adventurer was later to write the Adventures of Baron Munchausen (see Bentham’s letters, p. 287n, 335).

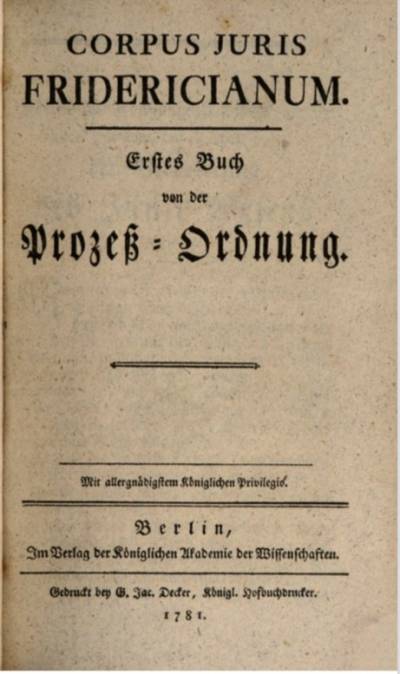

On April 14th, 1780, Frederick II announced that work on a code of laws should be taken up again, starting with the reform of civil law. The reform programme was set out by Carl Gottlieb Suarez and Johann Heinrich Casimir, Count von Carmer, in a volume published the following year.

Bentham did not read German. However, a review of this book published in July 1781 in the periodical Göttingische Gelehrte Anzeigen somehow came to his attention and he decided to write to Frederick the Great. In a draft letter written in French, the language he had in common with the King, he presented him with a copy of the recently printed An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation. These principles, he boasted “are equally good for London and for Berlin”. This code was “made for the needs of the eighteenth century and according to the needs of the eighteenth century”. But this draft remained unfinished and unsent, and no German translation of the Code, nor of IPML, came out at the time. (Manuscript sources: UC, clxix, 14-17).

Bentham’s contacts with Germany remained vicarious until the 27th of December 1787, when he arrived in Berlin, on his way back from Russia where he had been visiting Samuel in Kritchev. He remained in town for a fortnight. By then, he could not hope to meet Frederick the Great: the King had died in 1786. In Berlin, Bentham checked recent books on German jurisprudence and went to the Opera, as we learn from his correspondence (p.616). He spent most of his time with a Doctor Brown, an English physician employed at the court of Frederick-William, the new king. Little is known of his other activities.

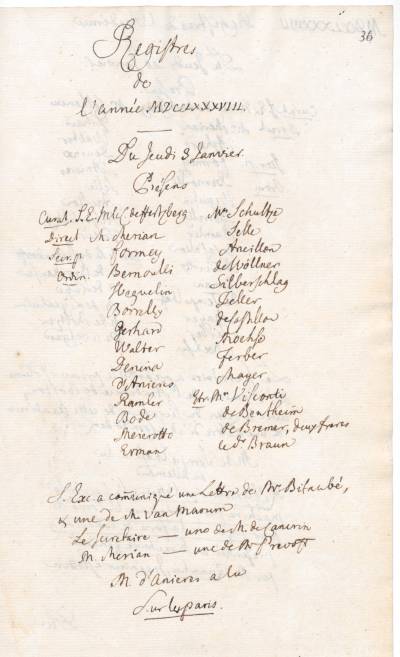

The registers of the Akademie der Wissenschaften, the German Academy of Sciences (follow this link for a digital edition of earlier registers), founded by Frederick the Great as a hub to attract Enlightened thinkers from across Europe however contain a trace of Bentham’s visit. Two of the foreigners who attended the session on January 3rd 1788 are certainly no other than Bentham and Brown, the spellings having been “Germanised” for the occasion into “M. de Bentheim” and “Dr. Braun”.

In Berlin, Bentham finally had the opportunity to brush shoulders with the cosmopolitan Enlightenment circles he valued so highly, even as an obscure visitor.

He would certainly have appreciated that Germany should be, 230 years later, a new hub for Utilitarian studies – and the Karlsruhe conference, with numerous panels on his thought and that of other Utilitarians, certainly did him proud.

Close

Close