Interview with: James Scott

James Scott is Director of Behaviour Change at Cycling UK, a not-for-profit organisation that aims to make cycling mainstream and make a lasting difference to the lives of individuals and communities.

24 July 2020

Interviewed by Kezia Stewart

With Cycling being ever more important to achieving a “green recovery” to Covid-19 we spoke to James Scott, the head of Behaviour Change at Cycling UK, to find out how they use the science of behaviour change to encourage more to cycle and what we need to focus on now.

Could you tell us a bit about your background and how you came to work in behaviour change?

I've been the director of behaviour change and development at Cycling UK for almost 3 years now, and prior to that as I was at Sustrans for 9 years in various different roles but for the last 2 years there as the head of behaviour change within London.

I started off in the Science Museum, in their education Department. So, my interest has been in helping people learn, which has always fascinated me. At University I studied how drama, psychology and theatre studies can change people’s perspectives, focusing on the social aspect. I was interested in and studied the work of Augusto Boal, who created plays that always had a problem to solve and performed plays which facilitated and encouraged community engagement. Members of a community could insert themselves into a play and help steer the narrative to ensure it had a positive outcome. I used this technique in quite a few projects within London with people that were recovering from drug & alcohol addiction, it allowed participants to talk about their experiences cathartically, and I suppose in a way work on choice architecture.

How I got into active travel started with my love for cycling. I started working at Sustrans in 2007 and was also competing in mountain bike races and then really got into the coaching, especially the theory and science side. I went through the different coaching pathways that British Cycling offer. Afterwards, I was contacted by UCI (the world governing body for cycling) to complete their diploma in coaching and became one of their worldwide expert coaches in mountain biking. The UCI liked my blended learning style of coaching and use of behaviour change techniques. I find behaviour change and coaching are very similar, especially at a practical level. I have taken this style and interjected it into many projects over the years.

I’ve always been really interested in the practical development of behaviour change and the last couple of years I’ve become more academic with the theory behind it. But I think that gives me a good grounding for what you can/cannot practically achieve with theory. I now work on how behaviour change ties into cycling specifically, Cycling UK policies and ensuring the projects we do are underpinned by behaviour change theory.

Given that behaviour change is so interdisciplinary, can you tell us a little bit about the professional makeup of the team and how you work together?

The team is the largest within Cycling UK with around 60 staff across Scotland and England. I have oversight over all that team, then there are two heads of behaviour change & development, who manage project managers who in turn then manage the staff that deliver the behaviour change initiatives on the ground. The professional makeup is diverse, ranging from backgrounds in sport development, teaching, trainers (cycling or outdoor education) to complete behaviour change geeks like me. Across the team we have a lot of experience in how to deliver and facilitate grass roots projects that need to get results quickly.

How is Cycling UK working to bring about sustainable behaviour change in active travel?

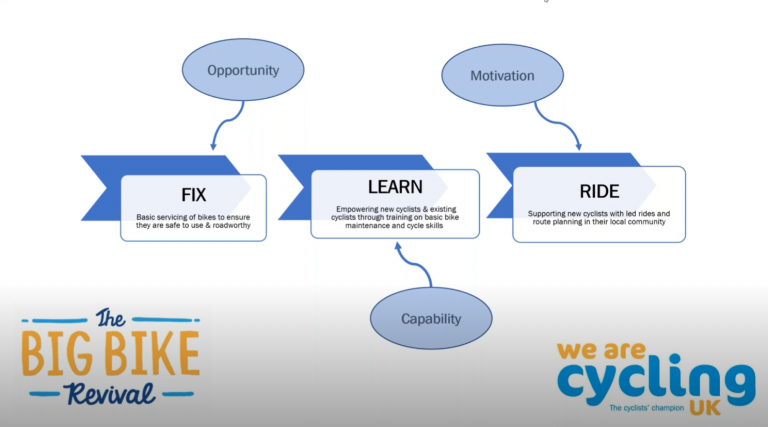

Changing people’s behaviour in the short term is easy-ish, having long term sustainable behaviour change is what we want to see. Only 2% of people travel by bike in the UK and that is heavily weighted to older males. The approach we use is practical on the ground interventions, the Big Bike Revival is a good example of that. We know that 42% of people have access to bikes, and the Big Bike Revival (See Figure 1) encourages people to bring their bikes to these events and they get a bike repair for free. From that entry point we take them on a behaviour change journey, that’s where the COM-B model comes in. We also utilise Self Determination Theory, participants on our schemes are keen to make their own decisions about future behaviour, we are here to help facilitate this, so theory’s such as Self Determination help us achieve this.

How did you find using these models to design interventions?

The COM-B I find quite easy to apply at a practical level, whereas theories such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour, though more popular (especially within transport) can be quite complicated at a practical level. However, COM-B does not work for everything. For example, where cycling is prescribed by doctors for health reasons it is much more a question of ‘motivation’, so we decided the PRIME model of behaviour change worked better for that one, this is of course closely related to COM-B and the Behaviour Change Wheel. We quite often use the EAST model too, once people have already decided to change their behaviour and have a degree of self-efficacy, model’s such as EAST help us to nudge/keep people engaged in the behaviour. We quite often refer to the Theoretical Model of Behaviour Change too. This helps ensure our programmes are following a narrative that is conducive to sustained behaviour change.

What I have learnt at a practical level is that taking some of the constructs from different models is absolutely fine. Although it may not be the academic’s vision for it, from a practical point of view it works well, particularly as I find different models often have similar concepts.

What are some of the hardest problems you have faced in applying behavioural change approach to cycling behaviour?

It’s very much at the back end of a program and how we gather and collect data. We are working with 60k people on some of our programmes, but trying to get back meaningful data is hard. We worked with the Behavioural Insights Team on a 6 month project into how best to collect survey data and even their conclusion was essentially “this is really difficult”. But they are brilliant, their own model EAST again lends itself to being really applicable and really practical. This all being said we do normally get about a 10% - 20% response on our surveys, which is enough to allow us to draw out trends and show tangible results from our programs.

Is there anything that you feel needs more development on either academically or professionally to better understand?

It would be great if we could come up with a behaviour change model for cycling. Within Cycling, the Theory of Planned Behaviour is being used time and time again perhaps where it does not fit. It would be great if we could try something new. This has been done for walking, as can be seen with the Social Ecological Model of Walking

Although there are theories of walking behaviour, cycling and walking at often lumped together in active travel, yet in terms of a behaviour they are very different. For example, one of the biggest differences in barriers is that people perceive cycling as dangerous, but people do not perceive walking as that dangerous. A cycling specific behaviour change model could help us understand how all different kinds of intervention need to work together to achieve long term change.

Much research supports the development of cycling infrastructure (such as segregated cycle paths) as one of the primary ways to increase cycling, however a lot of your work has looked at the “soft changes” that focus on behaviour, why is it important that these are also considered?

There is a really interesting paper on ‘How psychological theories can help cities increase walking and cycling” by Jennifer Dill, she has done a lot great work on active travel. The built environment has a huge factor in how we are going to interact with it and definitely helps dictate behaviour. However, within active travel there is a mentality that the mantra “build it and they will come”, will always encourage and guarantee behaviour change. Yet, within this paper Dill is saying, that while that is true to a certain extent, we should not underestimate the role that attitudes have on cycling. They recommend that cycle paths should be combined with soft measures to work on attitudes, and both are equally important. We really see this in a lot of the work we do and attitudes as a construct help dictate our programmes.

With the current pandemic situation there is increased focus on the role cycling can play in our future, where do you feel behaviour change work need to be done to make it a longer term behaviour change?

Of course, the pandemic has been horrific, but so many behaviours have changed and some for the better, such as travel choice. At the start of lock-down you could see people embracing active travel, cycling has more than doubled in some areas, how we travel has dramatically changed. And this has the potential to have some very positive outcomes and benefits, such as the reduction of C02 levels and encouraging people to lead active lifestyles that reduce diseases linked to inactivity. However, What I am really concerned about is that I do not want look back at this time and think “oh yeah you remember during the pandemic when more people starting cycling, wasn’t that great? Oh well, back in our cars now!” The time is now to push cycling and help build the behaviour into the public’s subconscious, so it ultimately becomes a habit. For this to happen we need political will, which looks to be there, especially with the minister for transport Grant Shapps and Chris Heaton-Harris minister for walking and cycling) they are making the right noises. But what is equally important as political will, is the funding to make it happen. So, the recent announcement on cycling measures and funding is exciting.

I think we also need wholesale approach, the pop-up cycling lanes we have that coming in is great, but it needs to be of a standard that people can use it. The science is there to prove that people aren’t going to interact with it when it’s not safe.

Alongside infrastructure we need soft measures such as rolling out Bikeability schemes and our Big Bike Revival for everyone, we also need policy changes such as creating more 20mph zones. It cannot be either hard or soft measures, it needs to be everything, we need people to feel that they have the capability, opportunity and motivation to get out and ride.

Close

Close