Health innovation: creative approaches to improving access to medicines globally

5 December 2019

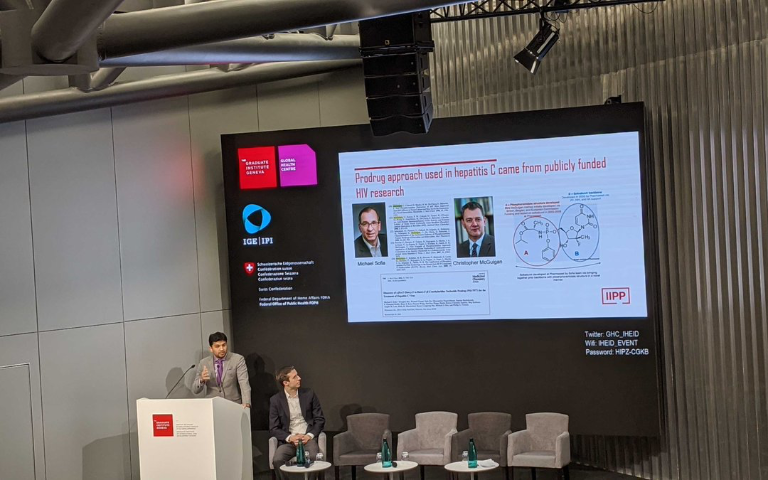

IIPP Fellow Victor Roy presented his work on the role of the public sector to deliver value through health innovation, specifically through the case of hepatitis C.

On December 3, IIPP Fellow Victor Roy travelled to Geneva to speak at The Graduate Institute, part of the Global Health Centre. The focus for this one-day symposium, organised in collaboration with the Swiss Federal Institute of Intellectual Property and the Federal Office of Public Health, was on the global challenge of improving access to new breakthrough medicines. Using relatively new curative treatments for hepatitis C virus (HCV) as an extended case study, the attendees pursued novel thinking around how to scale up treatment and also ensure that future breakthroughs are accessible to all who need them.

Roy, who is a practicing physician and completed a doctorate in the political economy of biomedical innovation, spoke on a panel that focused specifically on evolutions in innovation models. The panel featured speakers from the industry, including a member of Gilead Sciences’ public policy team as well as the head of Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative, a global non-profit R&D network. Roy spoke specifically about the significant role of the public sector in the process, and challenged the audience to reflect on the core principles that should underpin the enterprise of developing new drugs.

“Innovation not only has a rate but a direction. We often talk about the pace and speed of drug development but how do we realise those real breakthrough directions for health? Not just the incremental advances, but the kinds of medicines that transform care for a particular health need,” said Roy.

Roy used his platform to share ideas based on his research here at IIPP about the role of the public sector in facilitating long-term value creation. He argued that while the state’s contributions are often ‘black boxed’ as basic science, public investments play a key role across multiple stages of the process. The state is often the first entity to invest in long-term patient investment, harbouring the initial risks at the early stages and laying the groundwork, long before private sector businesses get involved. Then, once public sector-led research has created impressive breakthroughs in the field, the initial public sector success then crowds in private investment.

Giving specific examples of his research, Roy pointed to the case of the hepatitis C virus. For a decade after its identification in 1989, the hepatitis C virus could not be grown in cell culture in a lab, so drug developers had no efficient way to test components of the virus to stop the replication of it. However, thanks to investment from the German and US government, through the US Small Business Innovation Research Programme, funding the Charles M.Rice at Rockefeller University and his fellow scientists, they were able to develop the Hepatitis C replicon system (that allowed the virus to be grown in the lab). This paved the way for drug developers to revolutionise the treatment of this disease. Later, public investments also supported the start-up business that would ultimately develop the curative backbone of the most widely used hepatitis C treatment, sofosbuvir.

Yet access to the treatments were threatened due to the launch prices of the treatments in high income countries. The story of hepatitis C has been well documented in the media, including Roy’s 2016 piece in the British Medical Journal. In his comments in Geneva, Roy closed by asking an all important question: “How can we build ‘access’ into the design features of future innovation models? Not as a post-hoc consideration, but as an ex-ante design requirement?”

Read more

Rethinking Value in Health Innovation: from mystifications towards prescriptions

Rethinking Value in Health Innovation: from mystifications towards prescriptions

Close

Close