This zine explores the challenge of accessing support for children with special educational needs

Sarah (not her real name) is 9 this year. She loves comic books and likes to draw. Drawing helps her to express and think through her emotions. Twinkle, Sarah’s mum, explains that Sarah has autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and like 20% of people on the spectrum, Sarah experiences alexithymia.

“Alexithymia is a term to describe problems with identifying and expressing emotions. In Greek, it loosely translates to “no words for emotion.” It is estimated that 1 in 10 people have alexithymia, but it is much more common in those with depression and in autistic people” (Autistica 2021)

Although Sarah has no difficulty grasping academic subjects like Maths and English, often surpassing her peers in academic tests, she finds it difficult to master basic motor skills. PE is a struggle for her. She has difficulty buttoning her shirt and often feels embarrassed that her peers finish changing long before her.

“Research consistently shows that autistic children can experience both gross and fine motor delays and/or atypical motor patterns (e.g. Green et al. 2002). A research study by Johnson-Ecker and Parham (2000) showed that autistic children achieved lower scores in praxis tests (the ability to conceptualise, plan and co-ordinate movements to carry out a motor task) than their typically developing peers” (Laurie 2022)

As Twinkle explains, Sarah’s internal world often consists of worry and anxiety. Because she finds it difficult to read other people’s emotions or perform tasks that many of her peers find easy, she worries that they dislike her or think poorly of her.

She thinks everybody thinks she's not good enough, she's stupid or they don't understand what emotions she’s feeling. But these things, she is not like others in being able to understand. She cries sometimes because she can't control - She doesn't know how to express. So, she cries out. So everybody thinks why are you crying all the time? So she feels they don't understand me and they think I'm stupid or something.”

Twinkle

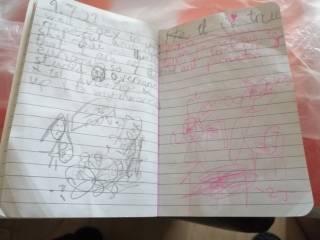

This is Sarah’s worry book, where she draws her feelings and explains situations that occurred in school to her teachers and mother. Her worry book, glittery and personal, was given to her by her school. When something happens, she draws out the scenarios that bother her:

I am so nervous to talk in front of 2J (that is her class) because I am not perfect, good and perfect . This is me and this happened. And this is someone (they were fighting about something). This is the 2J class. This is: you are in trouble. This is what she thinks: that the teacher is telling her you are in trouble. You did this. And she writes: Zoe is not respectful and kind, she made me think that I am not good and encouraging so I am stupid. Everyone thinks I am”

Twinkle narrating an entry in Sarah’s worry book

Drawings in Sarah's worry book, showing difficult situations at school and at home

As Twinkle explains, Sarah’s worries extend far into future scenarios:

She anticipates negative situations that have not happened. She will think: Oh, now they will think like this, and the teacher will shout at me. But these have not happened. So she thinks a lot, and she brings this home and sometimes when she sleeps she has bad dreams.”

Twinkle

Twinkle’s fight

Twinkle worries too, that Sarah will not be able to cope with difficult emotions and handle social situations on her own. She worries that because Sarah performs well academically, society will not notice her struggle, will not provide her with the support she needs, and worse, silently judge her for functioning “normally” but behaving differently. Constantly, Twinkle fights to prevent these worries from materialising. As she describes it, she is always trying to “change the surroundings for her [Sarah]”.

Twinkle’s fight to reshape the world occurs in daily events and struggles with the council, with teachers, with play groups, and most often, with society.

The EHC plan

Both Twinkle and Sarah’s school have applied 3 times for additional special needs support. The first 2 times, Sarah’s school applied for special needs funding from the council but were rejected. The third time, Twinkle applied for an Education, Health and Care plan (EHC Plan). This was also rejected.

“An Education, Health and Care plan (EHCP) is a legal document which describes a child or young person's (aged up to 25) special educational needs, the support they need, and the outcomes they would like to achieve. The special educational provision described in an EHC plan must be provided by the child or young person's local authority. This means an EHC plan can give a child or young person extra educational support. It can also give parents and young people more choice about which school or other setting their child or young person can attend.” (Hertfordshire County Council 2023)

For an EHC plan to be approved, local councils must first assess a child’s education, health and care needs. If they assess that the child’s needs cannot be met within existing school budgets, they will approve an EHC plan for additional support. Without an EHC plan, a child and their family must rely on existing school resources and personal funds.

Twinkle describes how this assessment process relies heavily on academic performance as a benchmark for development. Because Sarah performs academically well, she is not seen as needing extra help. Yet, she requires additional support for emotional and mental health needs that her school cannot provide. Psychosocial support such as modelling, training in self-management techniques and social skills training would help her immensely, particularly as she begins her transition from primary to secondary school. Twinkle worries about Sarah’s transition to adolescence: “I fear that the crowd there might not understand her if she doesn't understand herself. So it's best to now understand herself.”

Playgroup

Last year, when Twinkle was taking part in a research and training programme under UCL’s Citizen Science Academy, she applied to a school holiday playgroup so that Sarah could be taken care of in the day while she attended classes. Although the instructions for the playgroup application explicitly stated “if your child has special educational needs, please do not apply”, Twinkle applied anyway. Twinkle wrote to the playgroup explaining Sarah’s situation: although Sarah has special educational needs, she does not require constant supervision. All she needs is someone to regularly check-in on how she’s feeling. Eventually, the playgroup offered Sarah a place and she now goes there during her holiday breaks.

Twinkle doesn’t blame the playgroup for having a criteria excluding children with special education needs – they have limited resources and limited trained staff- but the limited availability of special needs playgroups speaks to a wider social failing. As Twinkle emphasises, “it shouldn’t be that way”. The demand for educational support, training and facilities to help people with special educational needs and disabilities has risen steadily in the UK, with local councils in particular seeing a sharp increase in applications for EHC plans (Office for National Statistics 2022). Yet, supply continues to lag behind as funding remains inadequate. A report by think-tank Institute for Policy Research North, based on an analysis of Department for Education data, found that the amount of funding available for each pupil with high needs fell from around £23,000 to around £19,000 between 2015/16 and 2018/2019 (Hunter 2019).

Help!

Twinkle highlighted that her situation paled in comparison to single parents or dual income households where both parents worked. Many of her friends with children in the SEND community worked full-time and found it incredibly difficult to access help. From experience, Twinkle has had to attend regular courses and events in order to find out information about the resources and support networks available. As she emphasises, this is something not all parents can do:

Help is very restricted to certain networks. If you go for sessions, you meet the professionals who have other information and who know other people. For example, they might tell you about some particular kind of travel support. You can’t just search the internet for it. But these sessions only run during school hours, weekdays. Not all parents can go“

Twinkle

Twinkle’s experience of navigating a complex system with no single point of contact and her friends struggles accessing support echo wider reports such as the House of Commons Education Committee’s inquiry into SEND provision, which found that families often faced an “adversarial and bureaucratic” system.

For many parents, the difficulty of accessing support and uncertainty around their child’s future can make a diagnosis of ASD terrifying. Twinkle knows of parents whose children have ASD but who refuse to diagnose them for fear of the stigma and potential obstacles in their lives. What if they can’t get a job because they are known to have ASD? What if people judge them? Twinkle feels that these biases cloud the future with negativity and make it difficult for parents and children to see ASD as simply another facet of a beautifully diverse life.

Ultimately, Twinkle feels that her fight is a fight against ignorance; against society’s lack of awareness and appreciation of ASD, which underpins stigma, judgement, lagging resources and inadequate support. As she implores: “You can't tell a parent you have to be understanding, but are you understanding it? The people who actually makes decisions?”

Just news (not bad news)

Sarah doesn’t know she has autism yet. Twinkle and her school have been slowly preparing to tell her but Twinkle doesn’t want the information to come to Sarah as “bad news”. She wants Sarah to know just how perfect she is and that her differences are just that, differences:

““Everyone is different in a different way. I would not change a thing about her, I would rather change.”

Twinkle

Indeed, Twinkle has changed by being Sarah’s mum and she wouldn’t have it any other way. She recounts how being Sarah’s mum has made her a better person - more patient, more understanding, more of a fighter – an ally and advocate. Twinkle hopes that other parents will find comfort and assurance too, and that through improved support and awareness, they will come to appreciate their child’s differences and change with them too.

Making places to be

Sarah’s school has been a major source of support and help for her, as well as Twinkle. In addition to multiple initiatives and adjustments they made to support Sarah’s emotional and social development, they also recently implemented a “place to be” - a space where psychologists and trained staff help children manage their emotions and mental health. Creating places to be for people with special educational needs and disabilities, however, isn’t just the responsibility of schools and parents, but of wider society as well. Sarah’s school offers a good example of what that might look like –listening to parents and children with special needs, working with them to make adjustments, and responding with care to issues when they arise. Twinkle stresses that this is an approach everyone else in society should adopt, especially policymakers, and that it requires a fundamental level of awareness.

To make society a “place to be” for people with ASD, Twinkle believes that everyone needs to understand how people on the spectrum experience the world. They need to understand the different ways that people experience their worlds, appreciate this diversity, and interact with kindness and care. In a similar way to her parenting approach, Twinkle would rather society change what it thinks is “normal” rather than force Sarah to its normal.

If you could speak to a policymaker now, what would you say?

The word ‘disability’ brings negative thoughts to anyone associated with it. It’s time to change it to ‘people with different abilities’, as we all are different – everyone has a skill that they are great at and some area where they need help. People on the spectrum are not trying to change anyone. They just want you to change the way you treat them, just understand and respect them for who they are”

Twinkle

Close

Close