Although quality of life in Coventry Cross has generally improved, barriers to prosperity persist in changed form.

Although quality of life in Coventry Cross has generally improved, barriers to prosperity persist in changed form. Racism now takes on a different hue. While overt racism has reduced, institutional racism remains the most significant barrier to improved life chances.

Barriers to opportunities for a better life have also shifted. Educational opportunities have significantly improved, yet access to employment, training, and further education remain stunted due to limited resources, mentorship, and signposting. Housing needs have also changed for some. While having a roof over one’s head is still an urgent worry for too many, over-crowding, maintenance, and safety are increasingly pressing problems for many living in social housing.

As barriers shift, however, residents seem accustomed to the lack in their life and inequalities that persist. “This is the best we’ll get”, “those buildings are nice because people pay for it” - mentalities such as these set in, normalising inequality and desensitising people to the possibility of better.

While the community in Coventry Cross has consistently stepped in to fill voids, help residents overcome barriers, and create positive role models, many felt that “there’s only so much a community can do”.

These are the messages, thoughts, and findings of Zeinab (not real name), a local resident and citizen social scientist from Newham, and Abdul, a long-time resident and citizen social scientist from Coventry Cross. The findings presented here come from an interview and focus group discussion conducted by Abdul, with members of his community, as well as an interview that Zeinab conducted with Abdul on the obstacles to prosperity in Coventry Cross. This research was conducted as part of the Prosperity in east London 2021-2031 Longitudinal Study.

Racism then

Abdul describes his experience with racism growing up:

““I went to school late 90s early 2000s, so that was coming to the end of racial tensions. I was growing up hearing stories of what happened the previous 10-20 years of actual physical fighting day-to-day. As I was growing up it moved from fighting day-to-day to being more vigilant and wary of other race groups...people from different races didn’t interact, there would be the odd fight here & there, and definitely fear of being attacked. As a teenager, early 20s. I could definitely feel institutional racism in the police force, specifically targeting and stopping and searching.”

Protest against the murder of Altab Ali, a Bangladeshi textile worker who was stabbed to death in east London, in a racially motivated killing. East London. 1978.

Racism now

Abdul describes how his experience with racism has changed, and the barriers he faces now:

““Over the past 10 years, the racism that I face has changed completely, from your day-to-day being called things or physically attacked to a more behind-the scenes institutional racism. Institutional to the extent where I felt I haven’t been as successful in a professional setting because of my name or the way I look. This normally happened closer to 9/11, I was too young then but in the 10-15 years after, it was a lot harder for someone like me. I’ve gone into interviews having that daunting feeling of knowing I’m not going to get it because I’m a brown guy with a beard. I definitely felt that, in workplaces I felt it, islamaphobia.”

Zeinab also describes her experience of racism and the expectation ceilings it creates:

““It’s the expectation of what you think you can do. I know someone who is studying and working at a university, she’s been talking to me about her struggles of not fitting in with the team. She’s a female and of an ethnic minority...one thing I hear her constantly saying is: it’s just been so hard.”

Her senior colleague didn’t seem to have an awareness or understanding of her not wanting to socialise in a pub or having alcohol. The senior colleague advised that it would work against her as

““you’ve got to do these things to connect with people. I have chosen not to do that [working in environments where religious or cultural standards may be questioned] because I know there’s a possibility it exists, I have decided to work in community settings - where I’m comfortable and excel, knowing very well financial rewards (higher income possibilities) are probably more limited.”

Anti-EDL (English Defence League) protests in Tower Hamlets. East London. 2013. Copyright Channel 4 News (C) 2013.

Opportunity: then

Abdul describes the opportunities available to his community in the 1970s and 1990s:

““During my discussion I found that during the 1970s-1990s, the main issue was that of racism, the fear of which did not allow residents to regularly leave the confines of the estate, which in turn affected the things they could do to make a better life for themselves. At that time, with residents being either immigrants or first-generation Bangladeshi, a greater focus was on providing for one’s family financially. As a result, further education was deemed to be out of reach.”

Bow School’s original Georgian building, built in the 1910s. Bow, London

Opportunity: now

Opportunities have changed over the years, however, and Abdul describes the shift:

““This slowly improved from the 1970s through to the 1990s. With that [overt racism] kind of dying down and provisions improving, access to better-quality education was a big help in the Bangladeshi community. In Tower Hamlets, most schools were completely renovated. Like my school didn’t have anything, it was just a mess, but now if you look at the building, the sports facilities, it looks state-of-the-art, and the schools have links to top universities and it’s become sixth form too. They have the whole trajectory mapped out for you to go to a good university.”

The new Bow School, opened in 2014. Copyright Bow School

Opportunity: where?

Yet, barriers to prosperity persist. In a focus group discussion and interview with Coventry Cross residents that Abdul conducted, residents highlighted reductions in state financial support for university education, dwindling infrastructure and funding to support community life, as well as a rise in anti-social behaviour, gang-related crime, and drug abuse among young people. These patterns seemed to crisscross and feed into each other - limited resources to fund further education, limited opportunities for training and employment, fewer positive avenues for leisure and positive life guidance all seemed to stunt people’s aspirations for a different life and contributed to a sense that a life of crime was comparatively “easy”. Quotes from Coventry Cross residents that Abdul spoke to reveal this pattern:

““Growing up in the 90s early 2000s, we didn’t have career advice on getting an education, jobs, managing family... I didn’t even realise the importance of going to university!”

Ahmed

““Naturally you think a good life is good education, get a job, have a good career but I think there’s more to life. It was a lot better when I was younger cause there were youth clubs, other evening sessions around this area, there was even day trips and community events. It seems they’ve all been taken away – budgets cut. It’s like they just want people to work, come home.”

Salman

““My eldest brother had the opportunity to go to university, but he had to work to take care of the family. When you live on the poverty line being able to take up opportunities is also about feeling like if you do something differently, you’re not going to risk putting yourself or family into poverty.”

Hassan

““Over the years, youth clubs have shut down and the local library is a shadow of what it used to be. Although new developments are being built, there’s so much empty undeveloped land that exists, which could easily be used to create community hubs for the betterment of locals.”

Nayeem

As Abdul further explains:

““During my research, there was a common theme throughout the decades, that despite barriers changing over the years, the single greatest barrier to people achieving the ‘good life’ has been a lack of access to opportunities that may have helped further them, be it employment, training, or further education. This not only meant not having resources or access to opportunities, but also not being directed or signposted to opportunities, not being sufficient advice at crucial points in their lives, not realising the importance of education or training.”

Housing: then

““It was as bad as you can imagine. If you imagine a working-class neighbourhood in the UK, whatever images and connotations come to mind, that is what it was. It was as bad as it can get...It was single glazed we had no security doors, potholes everywhere. Because it looked old the idea of people spraying graffiti didn’t seem like a bad thing to do because if it’s a mess, it’s a mess anyway.”

Communal walkway at a old council block in London. Copyright Shutterstock/Wei Huang

Housing: now

During renovations, Abdul’s estate had an underground rubbish disposal system installed. As Abdul says, “in theory it was amazing”. With new buildings cropping up, there was insufficient parking space for both residents of Abdul’s council estate and the new build. Cars began parking wherever they wanted, blocking up rubbish entry points. The council then provided white sandbags (normally used to hold construction materials) as makeshift rubbish bins - a stopgap measure that only seemed to worsen the parking situation.

Rubbish bags took up parking spaces, cars further blocked rubbish points, more rubbish accumulated, and more parking spaces were blocked, the cycle only seemed to worsen. As Abdul describes, this led to an unsightly and unpleasant situation:

““Loads of white bags overflowing with rubbish, it smells, you get flies coming into your house”

Abdul goes on to describe the housing inequality in the area:

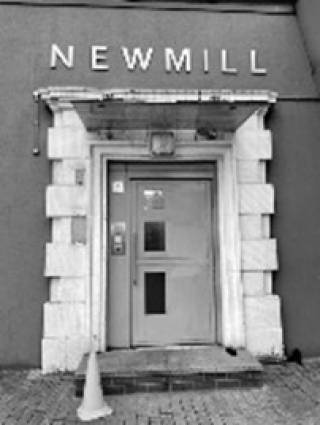

““This is a picture of the New Mill house. This is after renovations but it still looks very run-down. So when I described aesthetically very pleasing now, this is what I mean by very pleasing. It looks like it could do with a good clean but this is an improvement over what it was before. I do think upkeep is an issue. Compare that to some of the new build entrances. Can you see? Lobbies, concierge. Just 1 minute walk away from New Mill.”

New Mill Housing Estate. Coventry Cross. Abdul 2021

This is the best we’ll get

As barriers in housing, racial inclusion and opportunities changed over the years, Abdul describes how residents seemed accustomed to persistent inequalities:

““That’s what I’m accustomed to... I think cos we’ve seen such an improvement-you know how before I was talking about the job interviews and thinking I wasn’t going to get it anyway- it’s low expectations. A common expression during my discussions was the idea that perhaps people in the estate had internalised and ‘conditioned’ themselves to thinking that ‘this is the best that they will get’ despite growing up literally seeing the wealth of Canary Wharf ‘a stone’s throw away. When I mentioned this [disparity between council and private housing] to one of the youth in my area, I showed him a picture of the council flat and showed him a picture of the new build and he said ‘yeah but you can’t talk about that because these people paid for it’. They paid for it so that disparity shouldn’t be an issue.”

Communities filling voids

Despite facing multiple barriers to prosperity, Abdul describes the community in Coventry Cross as being resilient, cohesive and a key source of support over the years. Nonetheless, Abdul and his community worry that limited institutional support will prevent communities from continuing their good work and doing more to help. Abdul describes this experience:

“As a resident of Coventry Cross, I know first-hand the great sense of community cohesion that exists amongst residents of the estate. A worrying trend in my research was the role the community played over the past few decades in helping to fill the void left from insufficient state provision:

- Community cohesion

- Sense of belonging

- Pastoral care

- Spiritual guidance

- Training opportunities

- Recreational activities

- Educational courses

- Employment opportunities

- Community-building and well-being activities like residential trips, youth football, aerobic classes

“Many of which residents feel should be provided by the local authority. Community members involved in grassroots initiatives felt like ‘there is only so much that they can do’, with the future looking bleak due to ‘cuts in youth provisions’ and related funding.”

A Brief History of the Bromley-By-Bow Community Organisation

During the 70s and early 80s, at the height of racism and the National Front, youth from the Coventry Cross estate – being restricted to the confines of their estate and nearby areas – participated in a lot of football, taking part in a variety of football tournaments. Football allowed an escape from day-to-day life, building a sense of community and camaraderie. For the wider community, the local mosque was also founded, providing pastoral care and other faith-related provisions.

The various small teams formalised into an 11-a-side team in 1999, joining a league, giving the estate something to rally behind. In 2002, the team won a local tournament and were invited to a national tournament. By this time, overt racism was slowly decreasing, and other issues became more prevalent, such as easy access to drugs and the creation of gangs. No longer having to fight racist gangs, Bangladeshi gangs began fighting each other. The football team allowed people to coome together, stopping people from ‘hanging around’ and partaking in ‘anti-social behaviour’.

Over the next 10 years, as sponsorship money increased from the football team’s success, the team formed an umbrella organisation: Bromley-by-Bow Community Organisation (BBBCO), to help residents who weren’t interested in or associated with football. After a formal overhaul of the organisation, it became a registered charity in 2013.

Being completely community-led and voluntary, BBBCO has sought funding for and delivered mulitple projects over the years, even helping local schools and nearby estates outside of Coventry Cross. Starting with young people, BBBCO conducted research on their interests and organised residential trips, music workshops, community fun days, and volleyball tournaments. It also launched a youth football team, taking teenagers abroad on a footballing trip, allowing some to board a plane for the first time.

BBBCO did more research to see how other demographic groups could be helped, and organised aerobics classes for women, luncheons, fishing and fruit picking trips for the elderly, and funded local primary school projects – including breakfast clubs and the annual nativity play. BBBCO also organised accredited training for people to get into work and has empowered local people to help deliver some of its projects, providing work experience. One example is after-school tuition clubs during exam periods.

Although it started as a small football team, 70% of BBCO’s activities are now non-football related. They have helped raise residents’ quality of life and aspirations for decades. As barriers have changed over time, each generation has had the previous generation to look up to as an example of success and perseverance.

If you could speak to a policymaker now, what would you say?

““There’s so much physical and infrastructural development happening. But at local grassroots levels, what investment are you putting into the human aspects of life?”

Zeinab

““Involve residents in everything from the bottom up. Focus groups don’t work as people aren’t interested in taking part, or normally a certain type of person volunteers to be a part of one. People just want to get on with their lives generally speaking- so involve people by knocking on doors, speaking in schools, mosques etc.”

Abdul

Close

Close