The Verasur research project will investigate the long-term effects that repeated process of mobility and cultural interaction had on the regional histories of Mediterranean communities.

Project Aims:

- How did different instances of cultural contact affect local decisions?

- Did repeated cultural impacts create distinct societies that were better prepared to cope with change in the long term?

- How cultural influences provided varying solutions to Mediterranean problems of aridity and uncertainty?

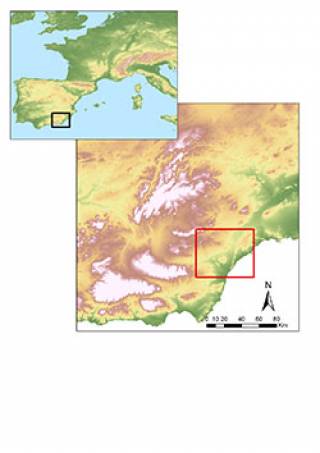

The project fuses the study of legacy data with information from new fieldwork to investigate the history of the settlement patterns, demographic history and resource exploitation strategies in the Vera region, SE Spain (Figure 1), from the Neolithic to the Middle Ages.

Project Goals:

- To produce a high-resolution deep history of the varying relationship between mobility and social development as seen through settlement patterns (location choices, site hierarchies, etc…).

- To record modern risks to the archaeological record of the region given the rapid economic development in the region and broader climate changes and provide information for the modern conservation of the sites

The Vera Basin

The Vera Basin is a typically Mediterranean region with its history shaped by inter-cultural contacts. It is one of the first areas to adopt Neolithic ways of life in Iberia and already in the 5th millennium the area has produced evidence that suggests an independent development of metallurgy (Ruiz-Taboada & Montero-Ruiz, 1999) and therefore a dynamic social and economic environment that encouraged technological innovation. In the 2nd Millennium BC the area was the cradle of El Argar culture, a complex social and political organisation.

By the first half of the 1st Millennium BC the Vera region saw the arrival of Phoenician culture and was at the centre of the transformation of the west Mediterranean. The next 2000 years would be marked by the impact of Mediterranean-wide phenomena of cultural interaction: Punic, Roman, Visigoth, Byzantine, Visigoth again and finally the Arab colonisation. The area encapsulates the landscapes and history of Mediterranean Iberia and it is a salient case of the lasting impact of cultural interaction and mobility on local histories.

The region also includes a rare rich history of research that started in 1880s with the Sirets’ excavations (Siret & Siret, 1890). A new wave of projects in the 1980s pioneered studies on the reconstruction of paleo-climate, paleo-landscapes and human impact in past Mediterranean landscapes with particular interest in process of deforestation and aridification typical from the region (Cámalich Massieu & Martín Socas, 1998; Castro et al., 1999, 1998; Castro et al., 2000; Delibes et al., 1996; Schulte, 2002; see Chávez Álvarez 2001 for a review). As part of these projects three archaeological surveys were conducted in the region and their publications provided a dense but superficial archaeological knowledge of the region before greenhouse agriculture and high-volume tourism changed the region (see Vallejo Sánchez 2010). The project builds on this information to build a much more detailed knowledge of the region.

Project’s Methodology

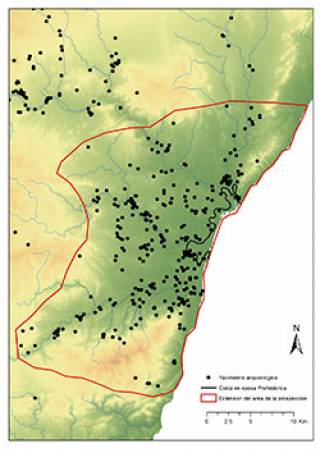

The project undertakes a tailored fieldwork methodology to unlock the potential of a large body of existing information on the archaeological record of the region. A new intensive survey in the region (Figure 2) together with the re-study of published and unpublished multidisciplinary data available is producing a high-resolution history of occupation of the region, including demography, resource exploitation strategies, production organisation, mobility patterns and territorial organisation.

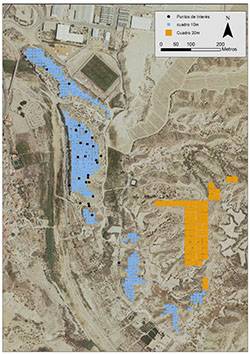

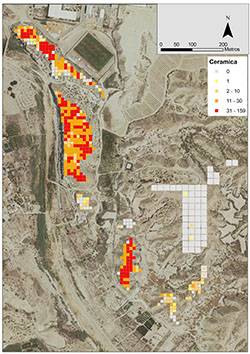

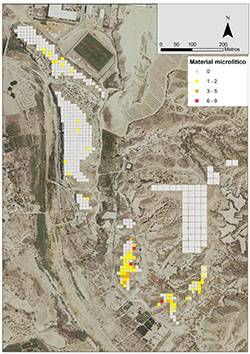

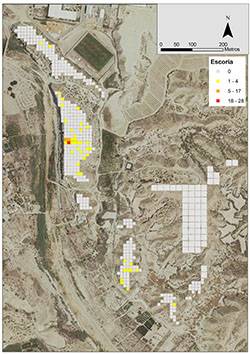

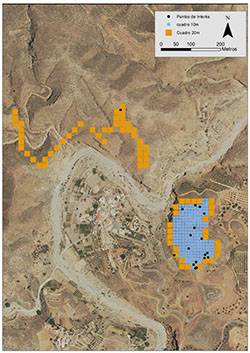

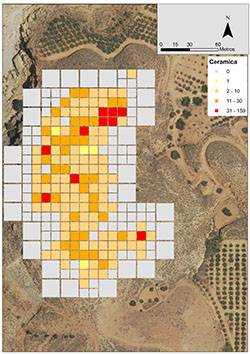

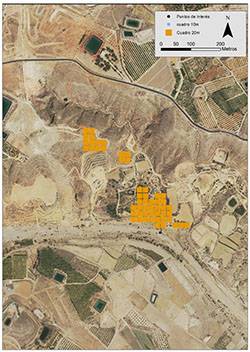

Intensive survey of known sites is undertaken by small teams in a 10x10 m. grid. At the centre of each square there is a full collection of material in an area of 10 m2 that is kept for specialist analyses. Remarkable items or materials within each square but outside the sample area are also collected and recorded. Information about visibility, vegetation and modern land-use is recorded for each unit. In areas of interest outside the settlements, the survey uses a grid of 20x20 m which is walked in two 1m wide transept. Material found within each transept is kept and studied. Other elements of interest, such as architectural remains, recent disturbances or current risks for the site are also documented in so-called Points of Interest (Puntos de Interes or PDI). Each is photographed, geo-referenced and added to a database. The material recovered is analysed by specialists at the University of Granada and UCL Institute of Archaeology, paying attention not only to decoration or shape, but also ceramic fabrics. This provides new information about dating, activities in the sites and relationships between sites in terms of technologies and consumption choices. This methodology allows to create an accurate dating of the history each site as well as define the extent of the settlements for each period of occupation and to follow changes in site size through time.

Available proxies for paleo-climate and paleo-landscape reconstruction (palynological studies, geomorphology, etc…) are also included to our own data in order to identify links between demography, settlement location and landscape changes and understand better taphonomic processes and how they bias our understanding of the region (Schulte 2002). Documented periods of change (moments of colonisation) will be targeted and compared diachronically (e.g. impact on settlement patterns of new populations, demographic impact in local populations, processes of settlement hierarchisation in relation to moments of cultural interaction, presence of foreign material in settlements, evidence of major shifts in agriculture from the palynological record, documented changes in technology).

2020 Campaign

A new fieldwork campaign will take place in May 2020. Further information will be posted here in due course.

2018 Campaign

In September a first field campaign took place over three weeks with a team of 7 people.

- First two weeks of work were centred on the sites of El Argar, La Gerundia y El Garcel. Definimos siete diferentes yacimientos en esta zona: El Argar; 2. La Gerundia; 3. El Argar 2; 4. EL Cabezo de El Garcel; 5. El Garcel; 6. El Garcel 2; 7. El Garcel 3 8. El Garcel 4 (Figures 3 and 4). The area of la Pernera was surveyed in a 20m grid around the site described by Siret. In most cases the visibility was very good and none of the sites is under modern use.

|  |  |

- Iron slag recovered in El Argar dates from the early Islamic period indicate a small industrial complex in the site (Figure 6. Schubart & Marzoli, 2015; see also Menasanch de Tobaruela 2000). The material is currently under study in order to understand better technological changes and organisation of production during the early Islamic period.

|

- The survey identified several points of interest in each site, including evidence of illegal excavations in El Argar. Also several other risks were identified such as natural erosion and water action but also modern works around the south side which have disturbed archaeological deposits in situ. La Gerundia has been heavily affected by modern illegal rubbish dumps.

- The site of Lugarico Viejo (Site 9, Figure 7) was also surveyed. Ceramic distribution indicates a site larger than expected that extends across the whole top of the hill. New traces of the Argaric Wall were also recorded. The slopes of the hill were surveyed in 20m. grids.

|  |

- The team also surveyed the area of Fuente Bermeja (Figure 9). Several other areas in the region were surveyed for other possible sites.

|

Acknowledgements and Thanks

- Museo Arqueológico Nacional

- Museo Arqueológico de Almería

- British Museum

- Junta de Andalucia

- University of Granada

- Dr. Lothar Schulte

- Dr. Margarita Díaz-Andreou

- Dr. María Dolores Camálich Massieu

- Dr. Dimas Martín Socas

- Dr. Dirce Marzoli

- Ayuntamiento de Antas

Funding

- British Academy

- UCL Institute of Archaeology

- Universidad de Granada

Close

Close