The Great Kyz Kala - one of the impressive medieval earthen buildings of the Merv Oasis that are currently being documented, researched and conserved.

A Short History of Merv

Merv lies on one of the main arms of the ancient Silk Roads that connected Europe and Africa to the Far East. The broad delta of rich alluvial land created by the Murgab river, which flows northwards from Afghanistan, forms an oasis at the southern edge of the Karakum Desert. The ancient cities of Merv developed at the heart of this oasis, close to the course of the main river channel in antiquity. The succession of cities, which together once encompassed over 1000 ha, date from the 5th century BCE to the present day.

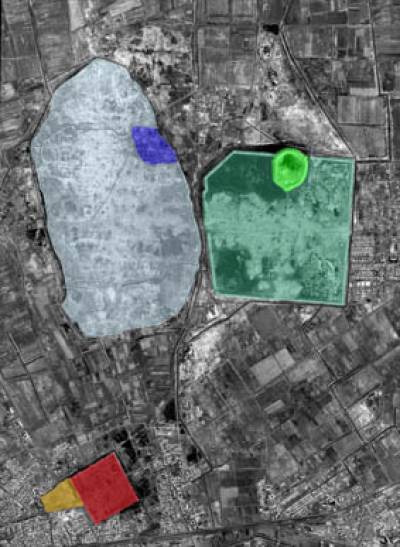

Annotated IKONOS image of the Merv Archaeological Park.

On the right of the image the light green enclosure is Erk Kala, Gyaur Kala (darker green) surrounds it. These lie adjacent to Sultan Kala (light blue), with the diamond shaped enclosure of the citadel of Shahriyar Ark (dark blue). Outside the contiguous zone of the park lie Abdullah Khan Kala (red) and Bairam Ali Khan Kala (orange).

In the 5th century BCE the Achaemenian Empire, stretching from Turkey to India and from Central Asia to Egypt, stimulated a growth in long-distance trade. A flourishing administrative and trading centre developed in the Murgab delta, now called Erk Kala. We know little about this first city: its city walls encompassed an oval area covering about 12 hectares, but as the earliest settlement lies some 17 metres below the modern day surface, buried under a sequence of more than 1,500 years of buildings and daily life, it is relatively inaccessible to archaeological exploration.

The region came into the Hellenistic world in the late 4th century BCE, as Alexander the Great swept through on route to the Oxus and India. The eastern territories of his empire soon became part of the Seleucid Empire, and Antiochus I (281-261 BCE) began a massive expansion of the city at Merv: the earlier city of Erk Kala was converted into a citadel and a vast new walled city was laid out, Antiochia Margiana (today called Gyaur Kala), nearly 2 kilometres across and covering some 340 hectares. Again, we currently know little of the detail of the early Seleucid city, buried as it is under a deep sequence of later occupation, although recent excavations of the outstandingly well preserved defences seem to confirm the Antiochus construction date, and give us a fascinating insight into the scale and organisation of the early city.

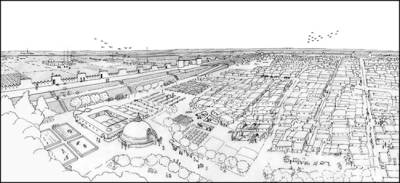

Imaginative reconstruction of the city of Gyaur Kala in the Sassanian period, by Claire Venables

The great city of Gyaur Kala was to develop with the ebb and flow of empires and trade over the next 1,000 years. The Parthians (from c 250 BCE), and then the Sasanians (from 226 CE), developed Merv as a major administrative, military and trading centre. The defences were repeatedly rebuilt and strengthened and the vitality of the city is reflected in the numerous building programmes and in the wealth of objects recovered from the excavations within Gyaur Kala. But there were also periods of decline, particularly when nomad invasions or migrations destabilised the area: during the 5th century CE, for example, Merv was probably the base for the disastrous campaigns against the Hephthalite Huns - during which the cream of the Sasanian elite were killed.

With the coming of Islam, in the 7th century CE, the urban landscape and the conduct of daily life began to change, as did Merv's role in the wider world. As the capital of Khurasan (the 'eastern land') Merv became a centre for Arab expansion, intended to relieve the over-crowding and religious and political discontent of towns such as Basra and Kufa in southern Iraq. A self-contained walled town, Shaim Kala, built outside the eastern gates of Gyaur Kala, perhaps to house these colonists (sadly this town has been largely destroyed under a Soviet planned village).

In the 740s the commander Abu Muslim took control of Merv, raising the black banners to proclaim the start of the Abbasid revolution. Baghdad was soon established as the capital of the new empire, but Merv's status as the capital of Khurasan had grown and now the empire from east of the Great Desert to the frontiers of India was administered from here.

Abu Muslim commissioned a mosque to be built alongside the Majan Canal, which flowed a kilometre to the west of Gyaur Kala city wall. There had been earlier occupation in the area; for example, by about the 7th century köshks, defended houses were being constructed, with massive corrugated walls perhaps the most striking buildings surviving at Merv. By the 11th century Abu Muslim's mosque lay at the centre of the thriving city Marv al-Shahijan (Merv the Great: today Sultan Kala). It is possible to see the mosque as part of the planning for the heart of the new city, which was clearly organised, with a planned street system and a carefully managed water supply (with numerous canals and reservoirs in each district). It seems likely that the new status of Merv in the 8th century, coupled with new ideas and beliefs that identified the need for public spaces, buildings, infrastructure - and perhaps most importantly, access to clean water, not only for domestic purposes but also for the practice of Islam - led to the deliberate and planned development of a new town.

As Sultan Kala rose to prominence the old city of Gyaur Kala began a gradual process of change and decline. Surface artefact studies suggest that the area of settlement contracted, and excavations have shown that the defences of the old city had fallen out of use by the 9th century. Along the main streets of the old city new industrial activities developed, turning it into the industrial suburb of the new city.

Sultan Kala continued to expand and develop through the Seljuk period (11th to early 13th centuries). Its walls enclosed some 340 hectares (a circuit of nearly 9 kilometres), with walled suburbs to the north and south encompassing an additional 210 hectares: at this time Merv was one of the largest cities in the world. Aerial photographs reveal a landscape of dense urban occupation on either side of the Majan Canal, with numerous streets forming a slightly irregular grid. Numerous large rectangular structures, interspersed within the tightly packed houses, mark the location of the some of the more substantial buildings. Markets, mosques and madaris proliferated, while substantial caravanserais were built within the city and along the main roads leading out, especially to the west. There was a large industrial quarter in the western suburbs, mainly producing pottery, including highly decorated moulded wares, which were in great demand along the trade routes. In the 12th century a walled citadel (Shahriyar Ark) was constructed in the north-eastern corner of the town, enclosing a palace complex, administrative buildings and high quality residences.

Merv had probably already started to wane by the later 12th century, as east-west trade had begun to be dominated by the seaborne routes between the Far East and Europe. By the early 13th century trade became disrupted by the movement of nomadic peoples to the east: the rising Mongol Empire. In 1221, a Mongol army arrived at the gates of Merv. They spent six days riding around the defences, looking for the weak points, before the town negotiated a surrender. Unfortunately, whatever the basis of the surrender was to have been, it was hardly a success. According to historical accounts the townspeople were massacred and the town burnt to the ground and abandoned. Various estimates have been given for the number of people put to death, ranging up to a million - however inflated the truth became in the telling, there can be little doubt that the scale of destruction and loss of life was horrific. Archaeological evidence suggests that the subsequent events were complex: there is evidence for buildings in the city of Sultan Kala continuing in use well into the Mongol period, and substantial quantities of Mongol period ceramics and industrial activity have been found within the city and its suburbs, possibly industrial zones surrounding a settlement in the citadel of the old Seljuk town. At present we have much to learn about how quickly life began again in Merv after the sack and the organisation of the Mongol settlement.

By the 15th century the old town was largely abandoned in favour of a new planned town, later called Abdullah Khan Kala, which was built some 2 kilometres to the south. This Timurid city was carefully laid out, covering some 46 hectares, with axial streets, a citadel area, baths, mosques and madaris, all enclosed by a defensive circuit. In many places this would have seemed a substantial town, and it was, but in the shadow of the vast Sultan Kala, it has suffered from the comparison, both in terms of its study and preservation.

Geographic Background

The majority of Turkmenistan is comprised of the Karakum Desert. Along the country's southern borders, however, runs the Kopet Dag mountains, with peaks in excess of 3,100 metres (10,170 feet), dividing Turkmenistan from Iran and Afghanistan. A number of small rivers and streams run down from this chain, until they disappear into the desert creating a fertile piedmont zone, while a number of more substantial rivers have created large fertile deltas and oases. The changing exploitation and hydrology of these water sources have shaped the shifting occupation of the foothills and desert margins over the past 4,000 years.

Landstat image of the Murgab delta, showing the dendretric nature of the oasis.

One of the most substantial rivers is the Murgab, which flows northward from the Kopet Dag mountains, forming a broad delta of irrigated land: the Murgab Delta. The ancient cities of Merv sites lay within this oasis: at times close to the course of the main river, but now some distance from the shifting main channel.

Close

Close