Introduction | Threats to the site | Solutions | Recent Progress | Future Work

The Ancient Merv Archaeological Park encompasses archaeological sites of the last four thousand years during which the main building material has been earth: sometimes made into mud bricks and bonded with mud mortar, sometimes rammed or placed into position, and nearly always covered with mud plaster.

The architecture and archaeology preserved in the Park is of international importance, partly due to the preservation of standing structures, such as the corrugated Kyz Kalas and the spectacular icehouses, and also because of the excellent preservation of over 1,000 hectares of buried archaeological deposits.

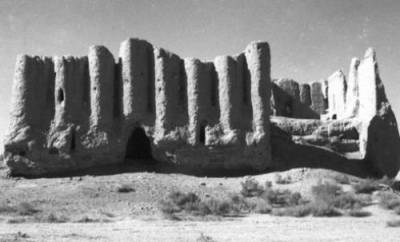

The east face of the Little Kyz Kala in 1954.

The same face of the Little Kyz Kala in 2003 shows how much erosion has taken place. The erosion is mainly caused by the wind.

For over two thousand years the main building material in Central Asia has been earth: sometimes made into mud bricks, sometimes rammed or placed into position, and nearly always covered with mud plaster (a mix of mud and straw). As people building in earth today know, such buildings need regular maintenance, with new coats of plaster applied to walls and roofs every few years.

Once the buildings and town walls at Merv were abandoned the process of decay started. Wind and rain steadily eroded the structures: once roofs had collapsed, walls lost material from both their tops and faces. However, the process was gradual, so buildings like the Great Kyz Kala have only lost about 1.5m in height over a thousand years.

In recent years, however, the process has accelerated considerably. The watertable in the Merv Oasis has risen due to the construction of the Karakum Canal. While this has brought major advantages for the agriculture of the region, it has been disastrous for the standing buildings. Water seeps into the bottom of the walls, and as this dries the salts in the water crystallise on the wall surface. This makes the surface much more fragile, and the wind removes the face of the wall rapidly. The result is great portions of the wall base collapse, and this process happens annually until the whole wall falls down.

Today the damage to the surviving earthen architecture and

archaeology at Merv is accelerating. The main problems

are:

Water (a)

rising groundwater - water seeps into the bottom of the walls,

and as this dries the salts in the water crystallise on the wall

surface, eroding the base of wall (undercutting).

(b) falling water - in the form of rain or snow damages earth buildings

and makes the surface much more fragile.

Wind. Wind removes the faces of walls. Wind can carry desert sand and this blasts and abrades the walls.

Vegetation. Plant roots can grow through and damage the earth walls and buried archaeology. Plants can also trap moisture, and lower the relative temperature, which can speed up damage to the fragile earth structures.

Animals. Humans move out and animals, birds, insects, and reptiles move in to earthen buildings. Animals can excavate burrows in earthen material, and by depositing their waste they can accelerate the rates of erosion.

People. Sometimes the people who come to visit the monuments in the park cause damage to them. This is because taking the same path through a monument can cause it to erode. In addition the park and the monuments are sometimes damaged by illicit activities such as robbing.

Conservation and Management Solutions for the Site

To find the best solutions for Merv we are undertaking experiments with traditional materials, such as mud plasters, mud mortars and mud bricks, as well as new materials, such as using a geotextile to separate the new conservation work from the archaeology. We are also using techniques that have been developed on other sites around the world, such as backfilling, alongside techniques more local to Merv, such as including wheat straw in mud plasters. We hope that by combining new and traditional techniques, with information from around the world, and from Merv, that we will find the best solutions for conserving these fragile earth structures.

During past fieldwork we undertook an evaluation of all the standing historic structures and extant archaeological trenches within the Archaeological Park, assessing their current condition, research and educational potential, and conservation priorities. This has been instrumental in shaping an emergency conservation programme for the Park, which is now underway. Some of the work we have undertaken so far includes:

STANDING BUILDINGS:

• Repairing eroded wall bases. The heavily eroded and undercut wall bases have been filled and packed with new mudbricks. These repairs provide support for the structure and limit the effects of damage from rising water, as the erosion occurs in the new material rather than the old material. In some places underground drains have been installed, and in other the original fired brick damp-proof course has been reinstated.

• Drainage works. Conservation work has been carried out to give the monuments better drainage. Simple measures like building low slopes are effective in redirecting water run-off from particularly fragile areas in monuments.

• Capping. Work at the top of walls is carried out to help water flow away from the structure. This is through placing new mudbricks or new plaster of the tops of walls. This 'cap' makes rain or snow fall away from the wall or structure and means the erosion occurs in the new material rather than the old material.

• Preparing damaged surfaces. Mud plaster surfaces that are damaged and cracked have been replastered using mud plaster and chopped wheat straw. These surfaces are regularly maintained to cover cracks and ensure they last longer.

• Replacing earlier conservation work. Some earlier conservation replaced the mud plaster finishes and surfaces on the monuments with heavier materials, such as concrete or cement. These harder materials were thought to last longer than the traditional finishes and surfaces. However they actually caused more problems, because they were heavier than the original materials and because these materials stopped the earth structure from being able to 'breathe'. As the buildings could no longer breath moisture could become trapped underneath the cement finish or surface. Where it has been possible, such as on the roof of Ibn Zeid, these harder materials have been removed, and they have been replaced with traditional mud plaster. These enable the building to 'breath' again, and with the regular maintenance of these surfaces the building can last much longer.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRENCHES

• Documentation and Backfilling. Archaeological excavations over the last 100 years have created a lot of open and eroding trenches in the archaeological park. These open and eroding trenches cause problems because they are big and deep, water runs off in to them. As they are cooler and attract water, vegetation, animals and birds live in the trenches, causing damage through burrowing and by depositing their waste. Because some of these trenches have been left open and eroding for such a long-time water, wind, plants and animals have caused the sides of the trenches to slump and have covered what remained of the exposed archaeology. To try to limit some of the damage that occurs to the trenches some of them have been backfilled.

Tamping down backfill material in Shariyar Ark to conserve the archaeological remains. In the background is 'geo-textile' which covers the walls and allows them to 'breathe' through the backfill.

Recent Progress

Remedial work has begun. The Archaeological Park has started to tackle the situation with a programme of cleaning and repair, along with the targeted repairs to support the most vulnerable structures. A team from CRATerre-EAG in Grenoble, under the direction of Sébastien Moriset and with UNESCO support, have constructed a laboratory for the Park, to explore the chemical properties of the soils and the best methods for developing sustainable new mudbrick and earth materials with which to repair and consolidate the structures. The World Monuments Fund , with support from The J.M. Kaplan Fund, Inc and the American Express Company, have generously supported the Turkmen/UCL/ CraTerre-EAG team, which has enabled a programme of "at risk" emergency repairs to the buildings within the Park. We have also undertaken a survey of the canal and irrigation systems, which has been used to develop a programme of targeted cleaning and repair, working with the local community to avoid some of the worst of the seasonal flood damage.

A further important part of this conservation programme has been the careful recording, by members of the archaeological team, of the areas to be conserved prior to the work beginning. In most cases this has involved photographic recording, but in certain cases excavation has been required. What is heartening is the way that the archaeologists, the conservators and the Park managers are working closely together to provide an integrated approach to these complex problems.

Progress on agreed priorities

1. Ben Hakri mosque, Gyaur Kala - initial research completed

and basic cleaning underway.

2. Palace (Shahriyar Ark) - clearance and drainage complete - underpinning

planned for Sept 2005.

3. Mausoleum of Ibn Zayd - roof maintenance, water spouts

and base of wall work completed. Still some problems with the quality

of materials, and water spout impacts. To be completed September

2005.

4. Great Kyz Kala - repairs of superstructure cracks, capping

selected wall sections & drainage channels completed.

5. Timurid House & icehouses - clearance of vegetation,

documentation, removal of debris, capping major wall cracks, and

improvement of drainage completed.

6. Abdullah Khan Kala - programme for emergency repair agreed.

7. Köshks in vicinity of Park - Porsy Köshk (Stinking

Köshk) documented, condition assessment undertaken, and action

plan prepared.

8. Entrance to the city of Erk Kala - major drainage channels,

exacerbated by visitor erosion: cleaned, documented and consolidated.

9. Archaeological section through Gyaur Kala defences - maintenance

programme established and implemented - improved drainage,

repaired structural cracks and cleaning.

10. Little Kyz Kala - monitoring conservation interventions

and modification of drainage.

11. Moat/canal west of Sultan Kala - 2kms main drain cleaned.

12. Old excavations - documentation, survey and reburial

of at risk sites in Sultan Kala & Gyaur Kala: two additional

sites documented and reburied Gyaur Kala; work planned for reburial

of so-called Rulers House in Sultan Kala in autumn 2005.

13. Artefact conservation & storage - current conditions

assessed and strategies being developed for future facilities as

part of new interpretation centre.

Background tasks

14. Monitoring - continued monitoring programmes.

15. Ben Hakri mosque and Firuz & Kushmiehan Gates - records

of previous work collated to enable interpretation and planning

of future conservation interventions.

Training programme

A three week training

programme was undertaken at Ancient Merv

Archaeological Park, between the 13th - 30th June, 2005. This

consisted of two courses:

• Course 1: Ethics, philosophy and approaches to the management of

Cultural Heritage sites. A one-week course aimed at a broad audience

from a range of Parks across Turkmenistan. Because of the practicalities

of Park staff availability, this was arranged as the middle week

of the programme.

• Course 2: Approaches to documentation of Cultural Heritage sites.

A two week course primarily aimed at the Merv Park Staff, but also

attended by some staff from other Parks. Practical elements of

the course included:

- documentation and condition assessment of Porsy Köshk;

- documentation of the conservation activities at Erk Kala;

- reburial of archaeological site.

Other conservation activities

Other conservation and management activities undertaken by June

2005 included:

a) Development of a new site management plan for the World Heritage

Site -additional sections have been drafted for consultation

in autumn 2005.

b) Reports have been prepared on the scale and speed of change

of the modern cemeteries in the northern and southern suburbs of

Sultan Kala. This information will enable the Ministry and Park

to open dialogue with the local authority, and community and religious

groups, in the hope of finding a solution to this encroachment

and destruction, while maintaining the social, religious and associative

values of the cemeteries.

c) Development of a glossary of conservation and architectural

terms in Turkmen & English.

d) Translation of existing project documentation and databases

into Turkmen - in progress.

e) Translation of archaeological recording manual into Turkmen

- in progress.

Future Work

The solutions to the conservation problems at Merv are not easy. It is our challenge to assess the problems and successes of the work we are carrying out and to build upon the existing knowledge as a means to help manage this unique site.

At Merv we are working closely between conservators and archaeologists, in particular in collaboration with Dr Kakamurad Kurbansakhatov (The State Institute of Cultural History of the Peoples of Turkmenistan, Central Asia and the East), Dr Mukhammed Mamedov and Dr Ruslan Muradov of the National Department for the Protection, Study and Restoration of Historical and Cultural Monuments, Ministry of Culture of Turkmenistan, and Rejeb Dzaparov, Director of the 'Ancient Merv' Archaeological Park, and Sébastien Moriset and Mahmoud Bendikir CRATerre-EAG (Grenoble, France). To see our generous sponsors who supported this work click here.

Close

Close