Understanding the fractured workings of urban development finance in Africa

1 August 2022

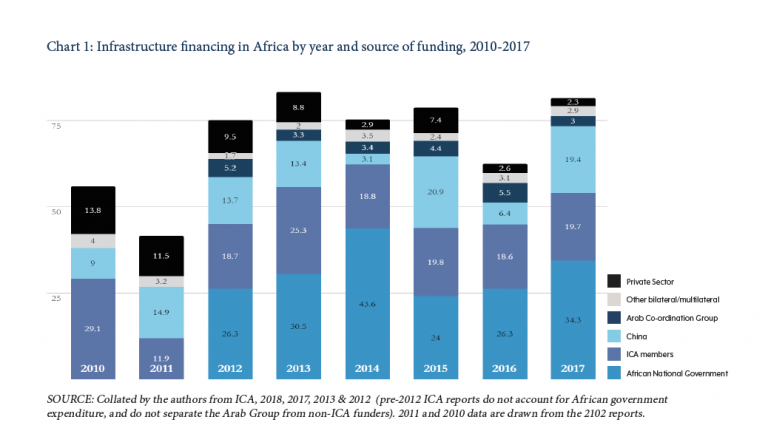

From the 2000s onwards, there has been a resurgence of large-scale infrastructure-led development in Africa, particularly in and between the continent’s urban centers. In this context of large-scale urban investments, much attention has been paid to the emerging role of private consultants, property developers and transnational corporations in reshaping African cities (Moser et al. 2021), even if the size of private sector investments remains relatively small. In contrast, with up to 30% of the total value of infrastructure projects in Africa, the contribution of Chinese investments to Africa’s urban transformation and infrastructure financing at large is undeniable (Goodfellow, 2020; Paller, 2021). However, a range of other powerful players, including some of the world’s largest bilateral donors, such as the US, UK and Japan, as well as multilateral development lenders such as the World Bank play a significant role in financing urban development and infrastructure in Africa (see Chart 1 below). These players interface both directly and indirectly with African national governments, who themselves are major investors in infrastructure development. This is because national governments are the main actors that have access to finance outside of their own revenues, whether through direct budget support, grants or concessional loans from development partners or through global financial markets, as evidenced by rising levels of national debt (Cirolia et al. 2021: 9-10).

Source: Cirolia et al. 2021 [1]

The rise in infrastructure investment in Africa is also coupled with an urban turn in global development policies and cooperation. This is marked by the adoption of a series of global and continental development agendas, including the United Nations Agenda 2030 with its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS), which replaced the previous Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), as well as the African Union’s own development Agenda 2063. By foregrounding the importance of cities in achieving these development agendas, cities are positioned as “pathways to sustainable development” (Parnell, 2016: 529). As such, urban investments represent a central way to close existing development financing gaps. To meet the SDGs in Africa by 2030 these have been estimated at US$ 1.3 trillion a year, far beyond current financial capacities (UNECA, 2020). Multilateral development banks such as the World Bank have therefore stressed the importance of fiscal decentralization to strengthen the financial capacity of African cities, ‘opening their doors to the world’ in order to facilitate access to new financial tools and global capital (Paulais, 2012; Lall et al. 2017).

Yet, despite this global discourse on the importance of cities and local governments, African national governments continue to be the main conduits through which urban – and mostly development – finance is channeled. This is evidenced by the limited extent to which sub-national levels of government in Africa can effectively mobilize revenues, control priorities, and engage in borrowing activities to finance investments in urban infrastructure and development. In contrast, development finance for infrastructure like highways and energy networks is largely controlled by national government departments, ringfenced government agencies, state owned companies or private agencies. Both the tensions between local and national government, as well as the proliferation of agencies which operate at the urban scale result in fractured fiscal authority and fragmented city infrastructures (Cirolia, 2020).

This institutional and spatial fracturing is a legacy of centralized colonial rule and of subsequent post-colonial political dynamics. Following independence, both newly formed African nation states and global investors shared a preference for centralized fiscal control (Dafflon and Madiès, 2013). For the former, this allowed for infrastructure development and planning to serve as a nation-building tool, while for the latter centralized development aid allowed for sustained access to decision makers and influence over country level processes (Beeckmans, 2018). In the years that followed, there were efforts to decentralize power to sub-national governments, in particular during the Structural Adjustment period. However, these efforts were also partial and contested (Riddell, 1997). In more recent years, as (particularly capital) cities have become both growing economic powerhouses as well as potential sites of political contestation, national governments and their respective ruling parties have tended to reinforce their grip over urban centers (Bekker and Therborn, 2012; Goodfellow and Jackman, 2020). The strategic importance of cities has translated into lip service to fiscal decentralization reforms, as this has become an important condition for national governments to secure international loans and investments for urban development. However, the desire to maintain political and economic control over cities means that this support has not effectively translated into environments that are more favourable to local government-led investments (Gorelick, 2018).

The mismatch between the increase in urban investments on the one hand and the persistently low levels of fiscal autonomy on the other requires close attention and is central for investigating the ways in which developmental investment circuits are able to shape local urban contexts in Africa. Central to analyzing the actions and practices of such circuits in our Making Africa Urban project is therefore the need to interrogate how these are shaped by different investment logics and actors, and how such logics in turn are both shaped by local contexts and localized in specific developments – embedded and territorialized across different scales. Key research questions that can be asked in relation to the study of the transcalar workings of developmental investment circuits in urban Africa are: How can we make sense of the central role of national governments in shaping urban development? How is this role shaped by global development finance circuits and what kind of infrastructural investments and development do these interactions produce at the local government level? Importantly, this requires a much better understanding of what both local and global development actors actually do, and how, where and what they invest in, beyond dominant development policies and discourses.

[1] In this graph, these actors are grouped together under the heading of ICA members, which represent the world’s G8 countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, the UK and the US); as well as South Africa, the first non-G8 G20 member to join the ICA. ICA members also include multilateral development banks such as the World Bank Group, the African Development Bank Group, the European Commission, the European Investment Bank and the Development Bank of Southern Africa. Arab funders include both domestic development institutions (the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development, the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development, the Qatar Fund For Development, the Saudi Fund for Development and the Iraqi Fund for External Development) and multilateral organizations including: the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa, the Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (AFESD), the Arab Gulf Program for Development (AGFUND), the Arab Monetary Fund, Islamic Development Bank, and the OPEC Fund for International Development. See more on ICA here: https://www.icafrica.org/en/about-ica/

References

Beeckmans, L. (2018). The Architecture of Nation-building in Africa as a Development Aid Project: Designing the capital cities of Kinshasa (Congo) and Dodoma (Tanzania) in the post-independence years, Progress in Planning 122, 1-28.

Bekker, S. and Therborn, G. (2012). Capital cities in Africa: power and powerlessness. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

Cirolia, L. R. (2020). Fractured fiscal authority and fragmented infrastructures: Financing sustainable urban development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Habitat International 104, 102233.

Cirolia, L.R., Pollio, A., and Pieterse, E. (2021) Infrastructure financing in Africa: Overview, research gaps and research agenda. Cape Town: African Centre for Cities.

Dafflon, B. and Madiès, T. (Eds) (2013). The Political Economy of Decentralization in Sub-Saharan Africa: A New Implementation Model in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, and Senegal. Africa Development Forum series. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Goodfellow, T. (2020). Finance, infrastructure and urban capital: the political economy of African ‘gap-filling’, Review of African Political Economy 47 (164), 256-27

Goodfellow, T. and Jackman, D. (2020) Control the capital: Cities and political dominance. ESID Working Paper No. 135. Manchester, UK: The University of Manchester

Gorelick, J. (2018). Supporting the future of municipal bonds in sub-Saharan Africa: the centrality of enabling environments and regulatory frameworks. Environment & Urbanization 30 (1): 103-122

Lall, S. V., Vernon Henderson, J., Venables, A. J. (2017). Africa’s Cities: Opening Doors to the World. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Moser, S., Côté-Roy, L. and Korah, P. I. (2021). The uncharted foreign actors, investments, and urban models in African new city building, Urban Geography doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1916698

Paller, J. W. (2021) How is China impacting African cities? Management and Organization Review. doi: 10.1017/mor.2021.43

Parnell, S. (2016). Defining a global urban development agenda. World Development 78:529-540

Paulais, T. (2012). Financing Africa’s Cities: The Imperative of Local Investment. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Riddell, B. (1997). Structural Adjustment Programmes and the city in tropical Africa. Urban Studies 34(8), 1297-1307.

UNECA (2020). Innovative finance for private sector development in Africa. Addis Ababa: United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.

Close

Close