Post-Soviet Press Pod

We are currently on a summer break and the podcast will resume in Term 1

In the podcast's first-ever series, "10 Minutes On...", we condense all you need to know about the 15 modern-day countries of the former Soviet Union, in a handy 10 minutes per episode.

Can't tell your Rose Revolution from your Tulip Revolution? Never tried kvass? Don't know where Moldova is? Then this is the podcast for you. From sampling traditional food and drink, to covering some of today's biggest news stories, we give you a whistle-stop tour of each country located in this incredibly diverse and exciting region.

Episodes are released every two weeks.

Episode Show Notes and Transcripts

- Belarus

Welcome to the Post-Soviet Press Pod’s "10 Minutes on…" series, which condenses the key information you need to know about each of the 15 countries of the former USSR into a bitesize 10 minutes(ish). In this first episode, we look at Belarus, which has been in the headlines since August 2020, when rigged elections led to mass protests against the rule of the “last dictator in Europe”, Alyaksandr Lukashenka. MA students at the UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES), Alex Figurski and James Bolton-Jones, discuss Belarusian culture, history, politics, and current affairs all while sampling some kvass - a delicious Belarusian beverage.

Hosts: James Bolton-Jones and Alex Figurski

Production: Alex Figurski

Editor: Alex Figurski

Academic supervisors: Dr Andrew Wilson and Dr Rasmus Nilsson

Transcript:

*Unscripted tasting kvass drink*

Alex: So, we’re just trying to open a bottle of kvass here. Right, there we go. Smells good.

James: За здароўе! (Za zdarowe!)

Alex: За здароўе! (Za zdarowe!)

James: Even if it is from different parts of the country…

Alex: It would be nice to see your face, but I can imagine you’re enjoying this.

James: Always. I love a bit of kvass.

*Short music intro*

Alex: So, welcome to the “10 Minutes” podcast series! I’m Alex Figurski, I’m joined here by James Bolton-Jones –

James: Hello

Alex: – and we’re both Editorial Assistants at the Post-Soviet Press Group, a news discussion group at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at University College London – and otherwise known as “SSEES”. As a press group, we focus on the current affairs of the countries of the former Soviet Union, so that’s 15 countries: from Estonia in the north, through Tajikistan in the south, and all across Russia to the Far East. That’s some distance covered!

James: Yes it is, and in each episode of this series, we’ll be focusing on one of these 15 countries in detail to give you all the basics you need to know. We’ll be covering things like language, culture, history and the biggest news stories affecting the country today – and we’ll be cramming it all into around 10 minutes per episode.

Alex: So, this week we’re starting the series with Belarus – a very important nation which suffered perhaps more than any other in the Second World War, often referred to as “Europe’s last dictatorship” and currently in the midst of one of the biggest protest movements of the 21st century.

James: That’s right, and to take us through this episode, we’ve got a bottle of kvass, which you’ll have heard us opening at the start of the show. It’s a famous Belarusian drink made from fermented bread and at 0.3% it’s technically classified as non-alcoholic, so hopefully UCL will be ok with us drinking it here.

Alex: Yeah, it goes way back to at least the 10th century doesn’t it, and nowadays you can get lots of different flavours – in Belarus, you have blackcurrant, raspberry, even vanilla, but we’ve got the classic plain one here. James, what do you make of it?

James: Yeah, I think it’s pretty good!

Alex: Yeah it is, isn’t it. Sainsbury’s finest import I believe. Right, let’s crack on with the rest of the episode!

James: Yep, let’s pour another glass and get going.

*Short music intro for rest of podcast*

Absolute basics

Alex: So, first things first, what would you say are some basic facts about Belarus that everyone needs to know?

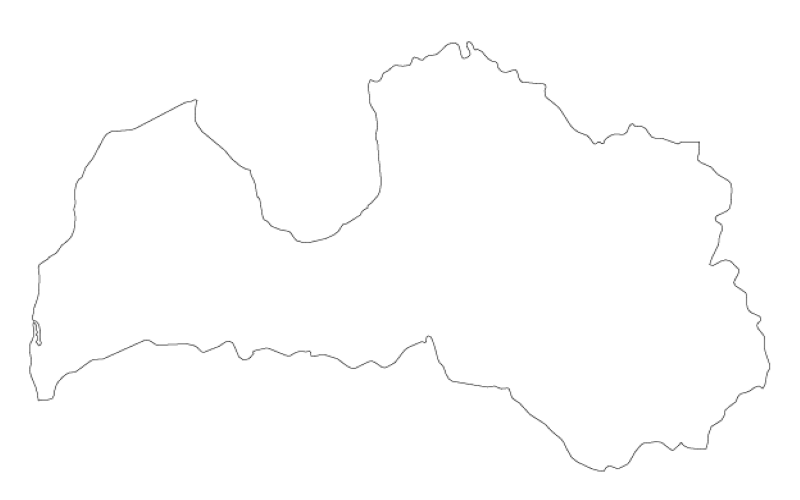

James: Ok, so Belarus is in Eastern Europe, nestled in between Poland and Lithuania to the West, Ukraine to the South, Latvia in the North and Russia to the East. It has a population of just under 9.5 million, which mostly speaks Russian, with speakers of Belarusian in the minority. A poll from 2009 indicated that fewer than 8% of Belarusians actually use the Belarusian language regularly.

Alex: And at risk of you butchering the pronunciation again, can you maybe say anything in Belarusian?

James: How about Хавайся у бульбу (Khavaisya u bul’bu)?

Alex: Nice, and what does that mean?

James: Well, it’s a saying that literally means ‘hide in your potatoes’! But you say it when something bad has happened, like ‘oh no, that’s not good’. Better go hide in some potatoes!

Alex: Speaking of which, we’re drinking this kvass, which is really going down very well. And if we were in Minsk, what food would we be having to go with it?

James: Well, for a snack to go with the drink we might be having Цыбрыкі (tsybryki) – think potato croquettes but fried in lard (although I fear I’ve once again wrangled the pronunciation, but there we go). But for a more substantial meal, it will still probably have potato in it, but there’s a huge variety, it’s not just about potato pancakes!

Alex: Ok, but potato pancakes are still delicious.

James: Yeah of course.

History

Alex: Ok, we can move on. History then. If most Belarusians speak Russian, presumably that means Belarus was part of Russia at some point?

James: Not exactly. So Belarus gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, and before that the territory of what is now Belarus was part of the Russian Empire.

But it would be a big mistake to think of Belarus as some kind of extension of Russia. Before today’s Belarus became part of the Russian Empire near the end of the 18th century, it was part of a polity known as the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth, and before that it was part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, also known as “Litva”. We should note that the term “Belarus” was not used at this point, with the local Slavic populations of Litva who would later become Belarusians and Ukrainians known as Ruthenians.

Alex: That’s a lot of names and dates!

James: And unfortunately it doesn’t stop quite there! Belarusian nationalists often refer to the city of Polatsk, which today is a small town in North-Eastern Belarus, as the place where Belarus began. It was first mentioned by chroniclers in 862.

Religion

Alex: And how about religion in Belarus? I know Roman Catholicism is popular in Poland, and Russia has a lot of Orthodox doesn’t it, so if Belarus has been under both Russian and Polish influences in the past, does it fall somewhere in between the two?

James: Yeah, that’s pretty much it. Belarus has always had several religions competing for its populace’s favour. We really don’t have time to get into the fascinating history of religion in Belarus here, but to give a very brief overview, Polatsk, which I mentioned just earlier many use as a founding myth for modern day Belarus, adopted Orthodoxy around the end of the 10th century AD, but when the Belarusian lands came under the control of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Roman Catholicism gradually became more popular, especially after the Kingdom of Poland started to exert more influence over the Grand Duchy. An important event to remember is the Union of Brest in 1596, when a new Church was created called the Uniate Church. This basically incorporated elements of both Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy, and became increasingly popular during the course of the next 200 years or so. However, when Belarusian lands came under the control of the Russian Empire, many Uniate believers were forcibly converted to Orthodoxy, and the Uniate Church was finally completely banned in most of the Russian Empire by 1839.

Alex: Religion was outlawed during Soviet times, right, so how has it fared since independence?

James: There’s been an Orthodox and Roman Catholic resurgence, with the President, Aliaksandr Lukashenka, enthusiastically promoting Belarus’ Orthodox credentials in the early 2000s, partly to emphasise historical ties with Russia, and remains pro-Orthodox to this day. Roman Catholics are the second biggest religious denomination, though they are often portrayed by the regime as a kind of Polish fifth column.

Back to History

Alex: Ok, so obviously the history of Belarus is long, complex and nuanced and we’ve inevitably had to gloss over a lot of detail just there, but we should very quickly mention an important event - the Second World War.

James: Yes, and it absolutely devastated Belarus, leading to, by some estimates, the death of a quarter of its population. Belarus was not only on the main route for the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, but also suffered from the way that they left as well during the Soviet “Operation Bagration”, which finally succeeded in expelling the Nazis from Soviet territory.

Belarus also once had a thriving Jewish population, with one of its most famous members being the painter Marc Chagall, but this was almost entirely wiped out during the Holocaust.

Alex: So what happened after Belarus gained independence in 1991? Did Lukashenka come to power straight away?

James: No. The first three or four years were pretty chaotic, but no one leader managed to consolidate their power. This changed in 1994 when Aliaksandr Lukashenka, who is actually a former pig farmer, ran for the new position of Presidency, created in 1994.

Alex: So is this the point at which Belarus becomes a dictatorship?

James: Not quite, though the 1994 election was certainly the only one which Lukashenka won fairly. After that, Lukashenka then set about targeting opposition figures, with a number “disappearing” without a trace in the late 90s, before winning all the subsequent presidential elections through a combination of election fraud, using the power of the state to secure votes, stymying the opposition and supporting fake opposition candidates who ended up supporting Lukashenka once he was elected.

News item

Alex: And that brings us up to the current day – and right now, Lukashenka is facing mass protests, which have been going on for many months. So what happened?

James: So a key date to remember is 9 August 2020, the day of the presidential election. When a dubious exit poll gave Lukashenka 80% of the vote and the main opposition leader, Sviatlana Tikhanouskaya, only 10%. Some then went out onto the streets to protest peacefully. But sadly, they were met with shocking police brutality, and when people saw the violence the state was using on its own citizens, that is supposedly the moment everything changed – and with each day, more people came out until it was hundreds of thousands every weekend in multiple cities.

Alex: Yeah, and in those first few days it was so inspirational how it seemed like every time they beat up a certain number of people, that only made more come out the next evening. So you said people did not believe the official election results. How did they know, has that been proven?

James: Well, this time around a group of tech-savvy civilians set up a website called “ГОЛОС” (“GOLOS”), or “VOICE”, asking people to take pictures of their ballot papers and send them in for an independent count. This was pretty clever – as obviously nobody can stop you taking a photo in a private voting booth. Out of the million votes they got sent, Tikhanouskaya got 95% and Lukashenka just 1% - which they say is enough to prove that Lukashenka couldn’t have got his 80% which he claimed he got, even if he got every other vote possible.

Alex: That seems like pretty damning evidence. I guess the question, then, is – why now? Why have people suddenly decided that they have now had enough of Lukashenka, after so many elections like this already?

James: So, there are several reasons. First is probably the weak economy and many say that Lukashenka has been losing legitimacy for many years now.

Second, the pandemic. Lukashenka’s response to Covid became infamous worldwide, as Belarus was one of the only countries to not go into any kind of lockdown.

Alex: Didn’t he tell citizens something like “drink vodka and go to the sauna” instead?

James: Yeah he did and unsurprisingly it’s widely thought to have alienated his support base.

Third, we should mention the role of some inspirational individuals. Like Sviatlana Tikhanouskaya – a former schoolteacher, whose husband was jailed for trying to run for President and so she decided to run in his place. There’s also Maria Kalesnikava – one of the key opposition figures who heroically tore up her passport when authorities tried to force her out of the country, so that they had to let her stay.

But most of all this has been a people’s movement, triggered by seeing and hearing about mass arrests, beatings and horrendous torture used by police on peaceful protesters. They simply had had enough and, in Tikhanouskaya’s words, they are not afraid of anything anymore.

What does the future hold?

Alex: And looking to the future now, what has the reaction internationally been to all this?

James: So, the EU has imposed personal sanctions on Lukashenka and other individuals linked to the regime and Tikhanouskaya, having been expelled from the country, is now travelling around campaigning for greater sanctions. Another important one to watch is the role of Russia. So far, the protests haven’t really been anti- or pro-Russian – just purely anti-Lukashenka. But for now, Russia seems to be backing Lukashenka, even if Putin doesn’t have a particularly great relationship with him.

Alex: And what about any other issues facing the country?

James: Well I think we’re running out of time so I’ll keep it brief! But there are lots of reasons Belarus is important, irrespective of whether Lukashenka is in power. It’s positioned at the border between the EU and Russia, and it remains to be seen whether it can develop closer ties with both at the same time. They are also crucial to the environment – it has a huge amount of forests, known as the “lungs of Europe”. And Belarus is still suffering from the legacy of the Chernobyl explosion in 1986, which contaminated huge areas of their land and there are fears it still affects the country’s food supply today.

Alex: Ok, we really are running out of time now! I think we’ll have to call it a day but before we do, we should also say a huge thanks to Andrew Wilson for his help in putting in this episode together. Andrew’s an expert on Belarus at UCL SSEES and his book on Belarus – Belarus: The Last European Dictatorship – is getting a new edition published imminently, so definitely, definitely worth checking out if you want to know more!

James: Perfect reading over a bottle of kvass I’d say.

Alex: Exactly. Bye, see you next time!

James: Bye!

- Russia

Russia Podcast

Introduction

Brief informal chit-chat

*Music intro*

Eleanor: Welcome to the “10 Minutes” podcast series of the Post-Soviet Press Pod! I’m Eleanor and I’m joined by Lara –

Lara: Hello

Eleanor: – and we’re members of the Post-Soviet Press Group, a news discussion group at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at UCL – otherwise known as “SSEES”. We focus on the current affairs of the 15 countries of the former Soviet Union, from Estonia in the north, through to Azerbaijan in the south and Russia to the east.

Lara: In each episode, we’ll be focusing on the basics: history, culture and news from one of these countries – and we’ll be cramming it all into 10 minutes.

Eleanor: So, this week we’re looking at Russia, a country in the news recently for political corruption and widespread protests, making it a hot topic.

Lara: Full disclosure: Eleanor and I had planned to wash down the traditionally Russian rye bread and lard with a vodka shot, but we lost our nerve and have decided to go for a nice cherny chai or black tea. Sadly, we don’t have a samovar – a large traditional tea urn – but a chainik or teapot we do have so let’s go.

Eleanor: I’m glad – I was not looking forward to shots in the morning. We might be on tea, but shall we still toast as if it’s vodka?

Lara: Absolutely! Tourists would say na zdorovie, but if you want to sound like a real local just say “za” plus anything you think is worth toasting

Eleanor: Alright, what about “To Russia!”, “To the podcast!” and “To SSEES!”?

Lara: Perfect. За Россию! (Za Rossiyu!)

Eleanor: За подкаст! (Za podkast!)

Lara: За SSEES! (Za SSEES)

*Audible clinks/sips*

Lara: Ok. Alright, alright. That’s enough toasts for one day. Eleanor, kick us off with the basics.

Basics

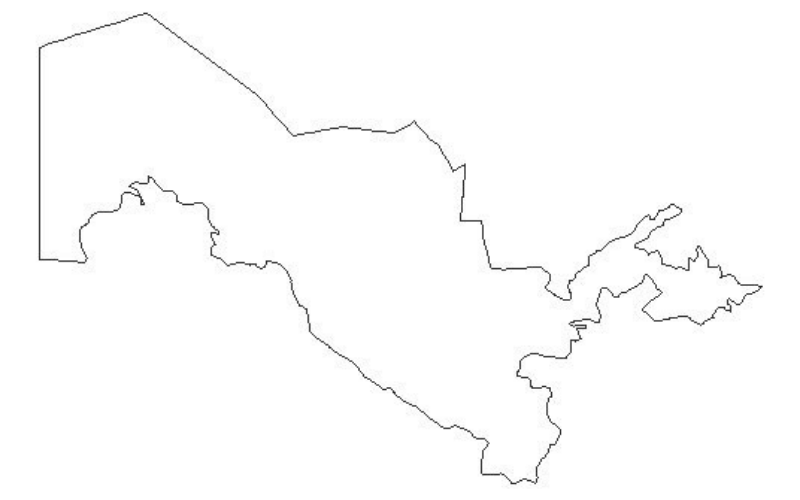

E: To start with the obvious facts: Russia, also called the Russian Federation, is the largest country in the world, and extends across eleven time zones. According to its constitution, Russia is secular, but the largest religion in Russia is Russian Orthodox Christianity. Russian is the official language of the Russian Federation, though there are 193 ethnic groups that speak over 100 different languages.

Lara: That’s pretty big. So tell us how Russia got so massive.

History

E: Well, we need to look at the history of Russia. The precursor to Russia was not so big. To start at the very beginning according to the oldest chronicle we have, called the Primary Chronicle, in the year 862 a group of Slavic and Finno-Ugric tribes invited a Viking called Rurik to rule over them.

The land he ruled is called Kievan Rus’ by historians but was basically a group of decentralised principalities run by Rurik’s alleged descendants. These principalities spanned from Kyiv – the modern-day capital of Ukraine – to Lagoda near Finland, to the black sea in the south and west to Ryazan. Fast forward to the year 988: Grand Prince Vladimir the Great decided that Rus’ should convert from paganism to Byzantine Orthodox Christianity.

L: Why did he do that?

E: Well, according to the Primary Chronicle he sent envoys throughout the world to see the major religions of the time. Islam was a no-go because alcohol and pork were not allowed – and, as Vladimir said, “drinking is the joy of all Rus’”. The adoption of Orthodox Christianity allowed Vladimir to unite the principalities of Rus’ under one religion and it strengthened ties with the richer, more powerful and more developed Byzantine empire.

L: OK so did Rus’ then develop ties with other empires?

E: They tried to but then the Mongols came knocking on Rus’ door and took over the territory of Rus’ from 1240 in what is called the ‘Mongol Yoke’, effectively cutting Rus’ off from the west. The Mongols did, however, open Rus’ up to the Silk Road and introduced the joy of tax collection. So, pluses and minuses.

L: How long did the ‘Mongol Yoke’ last?

E: Effectively until 1480 when Ivan III beat the Mongol Horde in the Great Stand on the Ugra, though by this point the Great Horde wasn’t very great or much of a horde.

L: Right, so when the Mongol Yoke ended did Russia become an empire?

E: No, but Ivan III did start centralising Rus’ under the principality of Muscovy. This was continued by his grandson Ivan IV, better known as Ivan the Terrible, who also started the large-scale colonisation of Siberia in 1555. Ivan IV was also the first tsar of Russia, a title derived from the Latin word ‘caesar’.

L: Where do the Romanovs and the Russian Empire fit into all of this then?

E: The Romanovs took over after a long dynastic struggle called the Time of Troubles from 1598-1613. Russia officially became the Russian Empire when Peter the Great assumed the title emperor in 1682. Peter the Great was keen to increase western influence on Russia and built the city of St Petersburg as a “window to Europe”. In terms of territory, from the 17th century to the 1830s the Russian Empire acquired Finland, all Persian territories and some Ottoman territories including Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan, Siberia, part of Poland, the Baltics and what is now Ukraine.

L: And that’s everything?

E: That’s most of it, yes. Nicholas II was the last tsar of Russia and under his rule we saw the 1905 Revolution and then the February 1917 Revolution, which resulted in Nicholas II’s abdication. Soon after the October 1917 Revolution, a civil war between the Bolsheviks (the Reds) and the counterrevolutionaries (the Whites) broke out. The Reds won, establishing the Soviet Union in 1922. The Soviet Union lasted until its collapse in 1991, after which Boris Yeltsin governed Russia as president for 8 years until Putin took over as acting president at the very end of 1999. Putin has remained president up to this day, with a brief interlude as Prime Minister from 2008 to 2012 when Dmitry Medvedev served as President.

L: Ok but hang on a minute… are you going to skip over the whole Soviet Union just like that in one sentence?!

E: No, but I thought this would be a good time for you as our culture expert to take our listeners through the Soviet to post-Soviet years through the prism of culture.

L: Well yes I quite like that idea.

E: Take it away then.

Culture

L: Ahem. The Soviet era was possibly one of the most exciting, dangerous and frustrating times for creative production in Russian history starting even before the 1917 Revolution. Revolutionary art was emerging as early as 1913 in the work of artists who would form the Modernist movements called Futurism, Suprematism and Constructivism. These movements rejected old Imperial tastes and demanded change much like social and political revolutionaries would a few years later.

E: So, were these Modernist movements purely to do with a change in fine art?

L: Not at all. Change was happening in all areas. Architecture, film, photography, poetry and literature. For example, in 1913 Velimir Khlebnikov and Aleksei Kruchenykh wrote the poetic manifesto Slovo Kak Tokovoe or ‘The Word as Such’. These poets took apart Russian words and stuck them back together in strange ways. Similarly, Kazimir Malevich presented familiar shapes in unfamiliar ways. His famous work ‘Chernyi Kvadrat’ or ‘Black Square’ painted in 1915 was the start of Suprematism, which influenced other fields.

E: Like what?

L: Take architecture. Lenin recognised that not only art but also buildings could impact the masses and unite them under the cause of socialism. Lenin thought that building impressive socialist palaces and monuments would inspire people to support the socialist cause. This is why Constructivist architect Vladimir Tatlin and his famous tower of 1920 was popular amongst the Party. It was too expensive to be built but was designed in this spirit of Modernism and revolution.

E: So, when Stalin came to power what happened?

L: Stalin introduced an art movement called Socialist Realism, which depicted a happy, harmonious socialist society. Think propagandistic but idyllic images of Stalin hugging children in the fields of an abundant Motherland – hardly a true reflection of the country he was starving and the people he was sending to the Gulag, a system of prison camps to which citizens were sent to do manual labour, often working to their death.

E: So, after 1953 – the year Stalin died – was there more freedom?

L: If only. The Soviet leaders’ policies on censorship remained strong and a lot of artistic creation was forced underground. That said, some works managed to slip through the net. For example, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s ‘One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich’, a tale of Stalin’s Gulag prison system, made it to print in 1962 in the Soviet Union and won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970. This did come at a price though, as Solzhenitsyn had to flee the USSR and live in exile from 1976 until 1990.

E: So, at what point did artists in the Soviet Union feel able to express themselves?

L: It was not until the 1980s that Gorbachev’s glasnost period – which translates as openness – allowed for a real explosion of freedom in art and mass media. This was the era of Moscow Conceptualist art and ironic Sots-Art, Russian rock music, and Chernukha cinema.

E: Chernukha? I’m assuming that comes from chernyi, the Russian word for black?

L: Exactly. This type of cinema took a dark view of Soviet life, seeking to undermine the past and show the grim realities of Soviet society. This tradition lasted into Yeltsin’s wild 90s too, when the Russian mafia was everywhere, and people found themselves living in a lawless, unpoliced state.

E: That takes us to Putin’s so-far more-than-20-year stint at the top. What cultural developments have we seen under his reign?

L: The term post-Soviet has definitely become a buzz word. In fashion, the arrival of Gosha Rubchinsky has led people all over the world to buy clothes with Cyrillic on without even knowing the meaning. Online, queer celebrities like Aleksandr Gudkov and YouTube journalists like Yuri Dud are encouraging progressive attitudes amongst Russian youth. That said, Putin’s cultural policies are still compared by some to Soviet-style censorship.

News

E: Speaking of censorship… now is probably a good time to discuss Russian news and the biggest headlines coming out of the country this year.

L: Definitely. What have you got?

E: I’m not sure if you’ve heard of a little global pandemic?

L: Yea, rings a bell.

E: So Russia has developed a coronavirus vaccine known as Sputnik V – “V” for “Victory” – and it’s 92% effective. The vaccine was initially met with a lot of scepticism, including allegations that certain companies were forcing employees to get vaccinated with Sputnik V, and others claiming the vaccine is a form of political competition as it shows Russia can compete with the West.Certainly, the vaccine is political, as the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sergei Lavrov, offered free vaccinations to the entire UN workforce. Some see this as a form of soft power in order to project a more positive image of Russia abroad.

L: As much as I love talking about Covid, we should really mention a man who has dominated the news since August last year.

E: Would that be Alexei Navalny by any chance?

L: Yes it would. As you know, Navalny is the most prominent opposition figure against the Putin regime and he was poisoned with a nerve agent called Novichok by FSB agents before boarding a flight from Tomsk to Moscow in August 2020. He became violently ill during the flight, resulting in an emergency landing in Omsk. After a few days, he was flown to Germany, where he spent months recovering. He returned to Moscow on 17 January 2021 and was detained at passport control on the pretext that he had violated parole conditions relating to a fraud conviction handed down in 2014 – a conviction that the European Court of Human Rights ruled was “arbitrary and manifestly unreasonable” in 2017. On 2 February 2021, Navalny’s suspended sentence for the fraud case was turned into 2 years and 8 months behind bars. The crime he is really being punished for, it seems, is exposing the most notorious cases of corruption connected to Putin and his inner circle on his YouTube channel and elsewhere online.

E: Wow – pretty classy to poison someone and then detain them for violating parole whilst they were recovering… Has Navalny gone quiet since his arrest?

L: Not at all. Navalny posted a video to his channel on 19 January – just two days after being detained – to send the message he’s not afraid of Putin. Titled “Putin’s Palace”, the video details the embezzlement and corruption that apparently allowed Putin to fund the construction of a ridiculously expensive private residence on the Black Sea. The video’s been viewed more than 100 million times. Then, protests across Russia began on 23 January and oppositional fervour continues still.

E: Definitely a story to keep an eye on then! Do you think that the opposition will actually be able to oppose Putin?

L: That’s a tough one. Putin certainly won’t make it easy as he’s constantly changing the law. In 2020 alone, he managed to pass sweeping changes to the Russian Constitution. The most important changes allow him to run for two more presidential terms.

E: So, we could be looking at how many more years of Putinist rule?

L: Assuming he wins the next two elections, and he remains in fit state to govern, he could serve as president until 2036, when he’ll be 83.

E: Wow, here’s to another 15 and a half years then! All this news raises a lot of questions like who will succeed Putin? If he remains in power, how will Russian autocracy and/or democracy evolve? Will the opposition succeed – and how will the West respond to Navalny’s calls for sanctions?

L: Well that’s for me to know and you to find out Eleanor.

Before we sign off though, we’d like to thank Mark Galeotti and Ben Noble for their expert help in preparing this episode and if you want to learn more about Russia, Mark’s book ‘A Short History of Russia’ will tell you everything you need to know. And Ben has a book coming out in September all about Navalny. Or, if you want to hear more about the cultural side of things, head over to the Russian Art + Culture podcast on Spotify and check out my new series called “Kusochek” as I interview a number of cultural experts about all areas of Russian culture.

E: Bye, then!

L: See you next time!

- Moldova

Introduction

*Unscripted brief informal chit-chat*

Alasdair: So, welcome to the “10 Minutes” podcast series of the Post-Soviet Press Pod! I’m Alasdair, I’m joined by Kristina –

Kristina: Hello!

A: – and we’re both Editorial Assistants at the Post-Soviet Press Group, a news discussion group at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at UCL – otherwise known as “SSEES”. As a press group, we focus on the current affairs of the countries of the former Soviet Union, so that’s 15 countries

K: In each episode of this series, we will be focusing on one of these 15 countries in detail to give you all the basics you need to know. We will discuss language, culture, history and the biggest news stories affecting the country today – and we will not take more than 10 minutes for each episode.

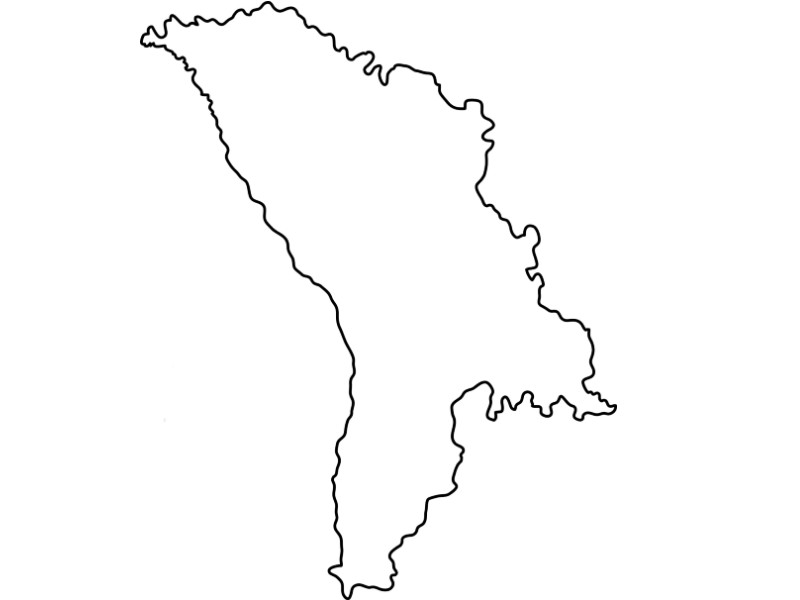

A: So, this week we’re starting the series with Moldova – an interesting nation which suffered through history as a cross-path of cultures and nations, often labelled as “Europe’s poorest country”, marked by the frozen conflict of Transdniestria and currently experiencing challenges between reformists and conservatives amidst the pandemic struggles.

K: Did you know that Moldovan wine is really popular as well? In fact, Moldova is home to Mileștii Mic – the largest wine cellar in the world stretching around 250km. Also, rumour has it that Putin keeps his wine in the second largest wine cellar in Moldova, in Cricova. Wine is so engrained in Moldovan culture that they even celebrate a national wine day in October!

A: Nowadays a large part of Moldovans engage in home produce of wine or home-made plum brandy, which is very interesting!

K: And if I was in Chişinău what traditional dish could I try along the Moldovan wine?

A: The mucenici are a traditional dessert used for the celebration of the Forty Martyrs on the 9th of March each year. Moldovans celebrate the Roman soldiers who were executed for refusing to apostatize their Christian beliefs. The mucenici are a traditional dessert for this celebration, I can best describe them as a sweet bagel in the shape of a figure eight.

K: Sounds delicious!

A: Let’s crack on with the rest of the episode!

*Short music intro for the rest of the podcast*

Absolute basics

K: So, let’s start with the basics – what does every beginner in all things Moldova need to be aware of?

A: Ok, so Moldova is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe situated between Romania and Ukraine. Its location is significant as historically, it was part of the Soviet Union and culturally the language Moldovan is considered linguistically identical to Romanian, nevertheless, Moldova is very much its own country with its own history and culture. It has a population of just over 3.5 million excluding the population of the breakaway region of Transdniestria of around 520,000. Ethnically, the population of Moldova is 75% Moldovan with ethnic minorities including Ukrainians, Russians, Bulgarians, Roma and Gagauz – a religiously Orthodox and Turkic speaking people

K: And what about your Moldovan language skills, do you have any words of wisdom?

A: Indeed, I do, in Moldova they say “Mulţi văd, puţini observă”.

K: Nice, and what does that mean?

A: It literally means ‘many see, few notice’. Мaybe this explains why many people seem to know very little about Moldova, it has been described as Europe’s best kept secret. We’ve all heard of Moldova but how many of us actually notice what goes on there.

K: But, if the language is considered to be identical to Romanian then why is it called Moldovan?

A: Well Moldova has a complicated history. During Soviet times, Moldova was known as the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, and during this time Moldovan adopted the Cyrillic alphabet to make the language more distinct from that of Romania, which of course was not a member of the Soviet Union. After the collapse of the USSR, the Latin alphabet has since been readopted and the Moldovan parliament has recognised that Moldovan and Romanian are, effectively, similar – although Moldovan speakers have a very distinctive accent.

Culture

K: That makes sense, what else can you tell us about Moldovan culture?

A: Well, this week our cultural focus is on music and the musical legends Moldova has produced over the years, some of whom you will all be familiar with, but you may have never even realised were Moldovan.

K: I’m listening.

A: I want you to cast your mind back to summer 2004. The sun was shining, school had finished for the holidays; nobody was wearing masks and no one had ever heard of Coronavirus. On the radio, number 3 in the UK top 40, number one in over 27 countries across the world, officially one of the bestselling singles of all time… it is of course “Dragostea din tei” by Chisinau boyband trio Ozone.

K: Are you not going to sing it for us?

A: I think we were trying to find out if UCL has a license to play registered music but I don’t know how far we got with that.

However, it’s not all boybands and Eurodance, in fact, one of Moldova’s most famous cultural figures is Eugen Doga the musician and composer. Born in 1937, he has a career spanning decades composing all sorts of different music. Perhaps, his most famous work is called ‘Waltz’ and this was used in the soviet film ‘A Hunting Accident’ also known as ‘My Sweet and Tender Breast.’ There is a famous scene in this film of a waltz at a wedding which is available on Youtube to watch. The scene was so popular that the waltz would be played at many weddings in the Soviet Union after this film was released. Ronald Reagan called it the waltz of the century so… it must be good.

K: Wow, so Moldova may be small, but it is not short of musical icons.

A: It definitely isn’t, but that’s enough culture for one day, tell me about Moldova’s history, where did it all start?

History

K: That is a very interesting question. Both Moldovans and Romanians originate from the Dacian tribes that inhabited these regions before and during the Roman empire and the Byzantine empire. The Daco-Romanian territory was subject to many invasions and influences. It was ruled over by the Bulgarian empire and Hungarian empire. It was also subject to Mongol, Tatar, Kievan Rus and Pecheneg raids. Specifically, the concept of the Moldovan entity goes back to the 14th century when the Principality of Moldavia became independent from Hungarian rule until the invasion of the Ottoman empire. In 1812, as a result of international disputes, the region of Bessarabia became part of the Russian empire.

A: So, this is why there are Russian, Ukrainian, Bulgarian and Gagauz minorities in Moldova. Gagauz refers to the Turkic speaking Bessarabian Christians. Also, in 1918 Bessarabia became part of Romania as an autonomous region however it was treated more like a colony. The large Jewish population in Bessarabia especially suffered as a result of anti-Semitism and fascism which spread across Europe eventually resulting in the Holocaust. So, when did Moldova become part of the Soviet Union?

K: The Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was established in 1924 as an autonomous region of the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic but this territory had never actually been part of Bessarabia or Moldovia, it covered what we now know as Transdniestria. In 1940, parts of this autonomous region were merged with some parts of Bessarabia, which was annexed from Romania. Thus, the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic was officially established as a part of the USSR.

A: Pretty straight forward then…

K: Indeed. But tell me… what has happened in Moldova since the collapse of the USSR and gaining independence?

A: The biggest challenge Moldova faced after 1991 was one of identity, the country became divided between Moldovan nationalists, Romanian nationalists and those who wanted to remain in the Soviet Union. As a result of these divisions, after 1991, Gagauzia in the south and Transdniestria in the east declared themselves independent mainly in defence to increasing Moldovan nationalism. We may explore how these breakaway regions pursued independence in future episodes.

K: And what about today is the country still divided?

A: Moldova has definitely undergone a massive political and socio-cultural transformation over the past 30 years and there have been significant achievements in stabilising the region and establishing democratic elections. Gagauzia is recognised as an autonomous region of Moldova whereas Transdniestria is described as a breakaway region. Officially, no UN member states recognise Transdniestria’s sovereignty and so it is considered a part of Moldova. Transdniestria’s independence is only recognised officially by Abkhazia, Republic of Artsakh and South Ossetia – states which also share limited international recognition in their claims for independence. So exactly what the future will look like in these areas remains uncertain. Recently, Moldova elected its first female president, Maia Sandu, who had previously led mass anti-government protests, can you tell us more about what happened here?

News Item

K: That’s right. In December 2020, around 20 000 Moldovans took to the streets headed by the oppositional parties in the government, because the Parliament was trying to restrain the powers of the president and this remains an ongoing issue. The problem is that the president Maia Sandu is from the opposition and the parliament is dominated by pro-Russian and socialist parties who attempt to keep the status quo. After several bills passed in Parliament that limited the president’s control over the intelligence services, Moldovans demanded resignation of their government. Since 1992 the country has oscillated between being strongly parliamentary and strongly presidential, in each case either the Prime Minister or President being the most powerful.

A: What happened after? Did the pandemic not influence public gatherings and behaviour?

K: Yes, to a certain extent. Currently the pandemic is impacting very negatively on life in Moldova as there are many cases but few restrictions because of the poor economy. Some protests continue, for example, demonstrations against the detention of Navalny took place recently. Civil activism is developing in Moldova as shown by the most recent elections in which there was growing support for the pro-European and anti-corruption candidate. Also, one of the most powerful oligarchs and ex-chairman of the Democratic Party of Moldova, Vlad Plahotniuc, fled the country in 2019. However, he still owns most things in Moldova and it is very difficult not to use things owned by him.

A: But the parliament is still dominated by Igor Dodon, the leader of the pro-Russian and socialist government, which came out of a split in the unreformed Moldovan Communist party of Vladimir Voronin and its members have been involved in a number of corruption scandals. They are currently also attempting to relaunch Russian propaganda channels in Moldova which were banned after the information war between Ukraine and Russia in 2018.

K: It is critical for Moldova since 2014, when three Moldovan banks were robbed of about 1 billion dollars which amounts to 1/8th of the GDP of the country. This scandal hindered progress that had been achieved beforehand in terms of European integration and democracy-building. Moldova’s land and climate are very fertile, and the country’s economy is based mainly on agriculture, but it is very difficult to compensate for the economic losses from the last decade and the corruption schemes. However, hopefully things will start to improve in the future. It is worth pointing out that Romania has made it very easy for Moldovans to acquire Romanian and thus EU citizenship. So many Moldovans have left to work in the EU as a result.

A: Well, this has definitely been an informative ten minutes, but we have sadly run out of time. Thank you to everyone who helped in putting this episode together, especially Dr Rasmus Nilsson and Dr Daniel Brett. Hopefully you’ve found it interesting and may even consider visiting Moldova one day once we are allowed to travel and have fun again.

K: Yes, I definitely would. Thank you everyone, goodbye.

A: Bye guys, see you next time!

- Ukraine

Hosts: James Bolton-Jones and Eleanor Evans

Editor: Kristina Tsabala

Academic supervisors: Dr Andrew Wilson and Dr Dave Dalton

PSPG podcast, 10 minutes on Ukraine

Introduction

10-15 seconds of non-scripted talk while serving ourselves some homemade borshch, noting how it tastes, perhaps saying “смачного” (bon appetit).

*Short music intro*

James: Welcome to this episode of the Post-Soviet Press Pod’s “10 Minutes on…” series, where, in each episode, we focus on one of the 15 countries of the former Soviet Union, covering the essential basics as well as things like language, culture, history and the biggest news stories affecting the country today – and we’ll be cramming it all into 10 minutes per episode! Your hosts today are me, James Bolton-Jones…

Ellie: … and me, Eleanor Evans.

James: Today, we look at Ukraine, and to power us through the episode we’ve each cooked up some homemade borsch. Eleanor, what can you tell us about borshch?

Ellie: So borshch is a delicious beetroot-based soup that is very popular in Ukraine, though no-one knows where it originally came from. I imagine most Ukrainians would say it was invented in Ukraine, though many Russians would probably claim the same. It’s typically eaten with sour cream, and with black rye bread to mop up the dregs. How’s yours tasting James?

James: Unscripted comment. Anyway, let’s get on with the rest of the episode!

*Short music intro for rest of podcast*

Absolute basics

James: Firstly, Eleanor, give us some quick-fire facts about Ukraine to get us started.

Ellie: Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe with a population of around 44 million people, neighbouring quite a few countries including Russia, Belarus, Poland and Romania. The main religion is Orthodox Christianity, though there’s some quite complicated context there which we’ll touch on later. The main languages spoken in Ukraine are Ukrainian and Russian. Speaking of which, can you say anything in Ukrainian, James?

James: Well, as it happens, I’ve been taking a class in intermediate Ukrainian at UCL this year. How about “хай вам щастить”, meaning “good luck”, which we’re going to need if we want to fit everything we want to say about Ukraine into just 10 minutes!

History

James: Let’s turn to history now. Ukraine gained independence in 1991, but what came before that?

Ellie: OK, so although Ukraine in the modern understanding began to be conceptualised around the first half of the 19th century, Ukrainian nation builders tend to focus on two much older polities which, in their eyes, contain the origins of the modern Ukrainian nation. The first one is Kievan Rus’, a polity that lasted from around the 9th century to the 13th century, when it was taken over by the Mongol Horde.Check out the episode on Russia for more details.

James: Yes, and the second polity that Ukrainians refer to is the Cossack Hetmanate, created by Ukrainian Cossacks in the 17th century. The Cossacks called their leaders ‘Hetman’, and in 1649 Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky defeated the Poles, who at the time controlled much of the territory which is now Ukraine and created what some view as the first Ukrainian state.

Ellie: The Hetmanate didn’t last for long though and was dismantled in 1785. In the 19th century, one part of what is now Ukraine was in the Russian Empire, and another part was in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In the Russian Empire, the people who would later become Ukrainians were called ‘Little Russians’, and in the Austro-Hungarian Empire they were called ‘Ruthenians’. The development of a national consciousness proceeded at different rates and in different ways in each part.

James: The collapse of the Russian Empire after the October 1917 Bolshevik Revolution and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after WW1 led to the creation of the first modern Ukrainian state, which united the parts which had been under both Empires.

Ellie: Yes and this survived in various forms until the 1921 Treaty of Riga, when the Bolsheviks and the Poles agreed to divide up Ukraine once again. Most of it became Soviet Ukraine and a couple of regions in the West became part of Poland. Small areas in contemporary Ukraine’s western borders also ended up in Czechoslovakia and Romania between WW1 and WW2.

Recent history since 1991

James: So, up to 1991, Ukraine was part of the Soviet Union, with its present day borders consolidated in 1954, when Crimea became part of Soviet Ukraine.

Ellie: Much of what is today Western Ukraine was part of Poland between the First and Second World Wars. But after the Soviet Union was on the winning side in the Second World War it joined the eastern and western parts of Ukraine together. Ironically enough, it was the leader of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin, who was responsible for uniting Ukraine.

James: Why do you say ironically?

Ellie: Well, Stalin was in charge of the Soviet Union during what is known as the “executed renaissance”, which was when the Soviet authorities killed or imprisoned much of Ukraine’s intelligentsia in the 1930s.

James: Stalin was also responsible for a man-made famine, also in the 1930s, known as the Holodomor, which caused the deaths of millions of people from starvation.

Ellie: So Stalin wasn’t exactly the most likely candidate to be the one to unite east and west Ukraine, then.

James: Definitely not. Let’s fast forward to 1991. Ukraine has its independence but it’s not all plain sailing from there, is it?

Ellie: Unfortunately not, though the communist regime was gone, many of the communist elites stayed in power, with the leader of Soviet Ukraine, Leonid Kravchuk, becoming independent Ukraine’s first President.

James: Yes and then he lost the 1994 presidential elections to another Leonid, this time Leonid Kuchma, who stayed in power until 2005. The previous year, 2004 was an important year for Ukraine, because it was the year of the Orange Revolution, when thousands of people protested on Independence Square in central Kyiv. They were fed up with the widespread corruption under Kuchma and were outraged by attempts to rig the election and put his preferred successor, Viktor Yanukovych, in power.

Ellie: Amazingly the protestors succeeded, with Yanukovych agreeing to hold new elections in which his opponent, Viktor Yushchenko, won.

James: But then Viktor Yanukovych won the 2010 presidential election and set about enriching himself and his family.

Ellie: This created general dissatisfaction with the Yanukovych regime, which climaxed in November 2013, when Yanukovych turned his back on an agreement with the EU and instead decided to sign an agreement strengthening ties with Russia.

James: This triggered protests – once again – on Independence Square in Kyiv. Efforts to suppress the protestors only increased their numbers, and things came to a head in February 2014 when over a hundred people were killed. Yanukovych fled to Russia, and Ukraine formed a new government, with subsequent elections making Petro Poroshenko the new President of Ukraine.

Ellie: Right, and these protests are often referred to as the Euromaidan, partly because of the fact that they were triggered by Yanukovych’s rejection of the deal with the EU, and partly after the word for square in Ukrainian – maidan, as the protests centred around Independence Square in Kyiv - Maidan Nezalezhnosti in Ukrainian.

James: But during all of this, Russia annexed Crimea and invaded the East of Ukraine, with support from local separatists, who proclaimed the creation of the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics. For the sake of balance we should say that there is a debate in academia about the extent to which this was a Russian invasion, a local uprising, or something in between. This state of affairs continues to this day, with Crimea now de facto part of Russia and the war in the East of Ukraine ongoing. And it’s worth emphasising that under Ukrainian and international law, Crimea is part of Ukraine.

Culture

Ellie: Moving onto culture, Ukrainian culture before independence was often incorporated into the cultures of the multinational Empires it was part of. For example. 19th-century writer Nikolai Gogol’ – in Ukrainian, Mykola Hohol – is often thought to be Russian, though he is from what is now Ukraine. But there were some Ukrainian cultural figures who were focused on developing Ukrainian as a literary language and on building the Ukrainian nation in the 19th century.

James: And the most important one of these has to be Taras Shevchenko. He was a serf from the Russian Empire who moved to St Petersburg to study art, after which a group of famous artists paid for his freedom.

Ellie: Right. Although Shevchenko was a great artist, his most lasting and influential legacy is his poetry, which standardized modern Ukrainian and turned it from a peasant language into a form of high art.

James: Exactly, and Shevchenko took inspiration from the Cossack Hetmanate which we mentioned earlier, and imagined the possibility of recreating a Ukrainian state in his own time.

Ellie: Moving on to contemporary Ukrainian culture, there are loads of great writers, musicians and artists working in Ukraine right now. I was particularly a big fan of Ukraine’s winning entry in the Eurovision song contest in 2016.

James: Yeah that song was amazing, though it was about a tragic moment in history, when the Crimean Tatar population of Crimea was deported to Central Asia in 1944, an event some have characterised as a genocide. The singer – Jamala – is a Crimean Tatar herself.

Ellie: Speaking of music, there’s another really good Ukrainian rock band called Okean Elzy. Their lead singer, Sviatoslav Vakarchuk, has been tipped to run for president one day, and he set up a political party which is represented in the Ukrainian parliament and is appropriately named Holos, meaning “voice” in Ukrainian.

James: We also said we’d mention some of the background to religion in Ukraine near the start of the show. What’s going on there Eleanor?

Ellie: Right, well, religion in Ukraine is complex, but I’ll try to be brief. A year after Ukraine gained independence in 1991, there were 3 different Orthodox Churches in Ukraine, one of which was linked to Russia, one called itself the 'Kyivan Patriarchate', and a third which wanted autocephaly, which basically means recognition as an independent church.

Brace yourself for some complicated organisational details. These demands fell on deaf ears until the outbreak of war in 2014. Due to the worsening of relations between Russia and Ukraine, the church that wanted autocephaly merged with another Orthodox church leading to the creation of a new church called the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, which then gained independence.

Current affairs

James: Phew, so after that whistle-stop tour through Ukrainian history and culture, what are the main issues facing Ukraine today, Eleanor?

Ellie: The two biggest issues are the struggle to implement and realise the spirit of reform which emerged after the Euromaidan and the ongoing war in the eastern Donbas region, which doesn’t look like ending any time soon.

James: No, sadly not, and though Ukraine’s current President, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, was elected on a promise to find a peaceful solution to the war, he hasn’t done so yet. Funnily enough, before entering office Zelenskyy was an actor and comedian, and he gained his presidential credentials by playing the President in a TV show!

Ellie: Wow, talk about life imitating art! So in terms of reforms, what are the main areas which need reforming?

James: A key one is Ukraine’s courts and its legal system in general, parts of which at the moment are very corrupt. Another connected issue is the dominance of the oligarchs in Ukraine, very rich business people who have an oversized influence on Ukrainian politics, the economy, the courts and the media. But the problem with reform is that all the key issues are interconnected, to such an extent that the challenges facing Ukraine could prove existential. For example, weak governance produces poor economic prospects, which then reduces the county's ability to defend itself from threats, like Russia, over the longer term.

Ellie: So you could say it’s not just about the relatively mundane question of "reform", but of whether the elite allows the country to develop the resources it needs to survive?

James: Exactly, and it’s certainly true that Ukraine faces some daunting challenges, though I have to say I remain optimistic overall. What would you say Zelenskyy is doing to deal with these problems, and what are the prospects for the remainder of his presidency?

Ellie: So Zelenskyy has around three years left of his term. Interestingly, the election of Joe Biden in the USA seems to be having a positive impact on Ukraine’s reform agenda, with Zelenskyy taking a number of measures to take on the oligarchs since Biden became president. This is not surprising, as, if Ukraine can show the USA it is trying to reform, it will receive a lot more financial and political support.

James: Yes, I saw that in February the National Security Council of Ukraine put sanctions on Viktor Medvedchuk, a pro-Russian politician close to Vladimir Putin who frequently takes stances which are very favourable to Russia. It was for that reason that the Ukrainian government also banned three TV channels which are said to be ultimately owned by him, even though the official owner is someone else.

Ellie: To sum up: measures are being taken, but it remains to be seen if Zelenskyy will truly get back on top of the reform agenda.

Questions for the future

James: All of this poses interesting questions about Ukraine’s future. Will these reforms continue to be implemented and will they succeed? Will there at last be peace in the Donbas, or will the war continue for a long time to come? Will Ukraine eventually join the EU and NATO?

Outro

Ellie: I would love to answer those questions that I most definitely have an answer to, but sadly we are out of time!

We would like to thank Andrew Wilson and Dave Dalton for their expert help in preparing this episode.

James: Bye for now!

Ellie: See you in the next episode!

- Estonia

Intro

*Short music intro*

Alex: They’re not that fishy at all though, quite a mild taste.

Alasdair: I quite like it.

**

Alex: Oh, we didn’t even say, this is – it’ll be even harder to pronounce with a mouth full of it – kiluvõileib.

Alasdair: Kiluvõileib

Alex: It’s actually quite good because it covers up our not being able to pronounce it.

Alasdair: Yeah. Also known as ‘sprats’.

**

Alasdair: I actually found a box of sprats in my mum’s car. She uses them to get my dog into the boot. Maybe she’s a secret Estonian.

Alex: Wait, so your mum actually had it in the car?

Alasdair: Yeah. My mum was like ‘Oh I’ve got some sprats to get Archie in the car’.

Alex: But then you’ve got a tin of sprats open in the car, it’s a mess?

Alasdair: That’s what I mean, that’s why she’s got the Tupperware lid. But it didn’t smell of fish but I was kind of shocked when I opened the boot.

Alex: I feel like we’ve learned more about the power of a dog’s scent than Estonian food, but we’ll get onto that.

**

Alex: So, here we go again. Welcome to another episode of the “10 Minutes on...” podcast series, I’m Alex, I’m joined by Alasdair –

Alasdair: Hello

Alex: – and in this series, we’re covering all the basics you need to know about each of the modern-day countries which used to be under Soviet rule: their culture, history and current affairs. And today we’re talking about Estonia, one of the three former Soviet Baltic countries. I’m looking forward to it!

Alasdair: Yeah, it’s exciting. Estonia is pretty distinct from other former Soviet states, just like all of the Baltic countries really, so it’s a good one to do. Even when it was part of the Soviet Union, it always had its own very strong national identity.

Alex: That’s very true, and today we’ll be talking about extremely long Estonian words, about how the country fought for its independence by singing, and about how the capital city, Tallinn, has developed in the post-Soviet years.

Alasdair: Before we do that, we should mention the lovely kiluvõileib we’ve been eating at the start of the episode, i.e. sprat sandwiches (with sprats being small fish common to the Baltic Sea).

Alex: Yeah, honestly they are excellent. So these are open-top sandwiches, with rye bread, butter, sprats, a slice of boiled egg and chopped spring onion. It’s a very popular snack in Estonia – and Alasdair and I have channelled our inner Estonians and made ourselves some at home.

Alasdair: Yeah, I have thoroughly rated them. I think I might be having kiluvõileib again one day.

Alex: Good thing they taste good as I’ve got about five tins of sprats at home now. Right, shall we get going then?

*Short music intro*

Basics and Culture

Alex: So, I mentioned extremely long Estonian words, and that’s probably a good place to start. Alasdair, if I were to say to you: imagine it’s your birthday week, right –

Alasdair: Right

Alex: – and you’re coming to the end of it, it’s the weekend, you’re having a party in the afternoon and you’re probably feeling a bit tired because you’ve been partying all week. So, amazingly, in Estonian, you can actually express that exact emotion and scenario with just one 42-letter word. I’m not even going to try to pronounce it but I will ask Estonian Google to say it instead:

Sünnipäevanädalalõpupeopärastlõunaväsimus (x2)

Alasdair: Impressive

Alex: Yes, so its precise meaning is: “the tiredness one feels on the afternoon of the final party of the birthday week”.

Alasdair: That’s how I felt after this bank holiday. Do people actually use this word?

Alex: Yeah I don’t think so. So, if you’re travelling to Estonia and want to learn some key phrases, probably worth memorising a few others before you get to that one. But the point is, the Estonian language can be quite tricky because it is an “agglutinative” language, meaning it often “glues” together short words to make long ones. Theoretically, you could have a word that is even longer than 42 letters, and there are a lot of people having fun on the internet trying to come up with new words to beat the record.

Alasdair: That’s interesting that it can be a difficult, and also very different, language because, after gaining independence from the Soviet Union, there was a large minority of ethnic Russians who had migrated to Estonia for work, many of whom did not speak Estonian at the time and many still don’t. Language is one feature of ethnic tensions in Estonia, but maybe we’ll come onto that a bit later.

Alex: Definitely. Well, Estonian is of course the national language, but there are Russian-speaking regions in the north-eastern county of Ida-Virumaa and parts of the capital Tallinn.

Alasdair: Let’s talk a bit about Estonian culture as well because it’s got various Nordic, Baltic and Germanic influences.

Alex: Yeah so, Estonia is a North-Eastern European country. It borders Latvia to the south and Russia to the east, but it is very near to Finland and Sweden across the Baltic Sea. The language is very close to Finnish but comparing it with Latvian or Lithuanian by contrast is a bit like comparing English with Japanese, it’s totally different. Like Latvia, Estonia does have some Protestant influence from past Baltic German rule, though today it’s actually one of the most secular cultures in Europe.

Alasdair: One thing all Estonians love, though, is a good sing-a-long.

Alex: Yes! Really, for a nation that is stereotyped as introverted, singing is its speciality. We’ll probably talk later on about the ‘Singing Revolution’, when Estonians gained independence through song, though major events like the Song Festival, where 30,000 Estonians come together to sing in unison, they’re still a big part of national culture today.

Alasdair: Sounds like karaoke in Tallinn would be fun.

Alex: Yeah, or any kind of night out really. What else should we say about Estonian culture?

Alasdair: There’s a sort of national pride in the natural environment too which is quite interesting. Estonia’s quite flat, but around 50% of it is forested and it has over 2,000 islands on the Baltic Sea. Though the vast majority of people live in the city, that link to nature is fairly important. Lakes, woods...

Alex: … hiking, wild camping.

Alasdair: Yeah, the outdoors. It’s a big part of Estonian way of life.

Alex: Sounds like an ideal place for Bear Grylls.

Alasdair: Indeed. Though you’re more likely to pick wild berries and mushrooms than have to scavenge anthills for your food.

History

Alex: Yeah, tasty. Let’s talk a bit about Estonia’s history then. Where should we start?

Alasdair: We can start as far back as the 1st century AD really. Estonia has a long history which is characterised by constant struggles against foreign invaders. Knowledge of tribes living along the eastern shore of the Baltic sea dates all the way back to when Roman historian Tacitus described them as Aestii, who lived within systems of clans and elders. This is interesting as even in the 1920s and 1930s, Estonian governments had the title of State Elder (riigivanem) to describe the combined office of prime minister and head of state. The first recorded example of a foreign invasion of Estonia was in the 9th century when Vikings moved down the Baltic coast.

Alex: There’s that Nordic connection again.

Alasdair: That’s right, and after the Vikings, Estonia was fought over by numerous European and Christian colonisers. Throughout the Middle Ages all the way up to the twentieth century, Estonia was fought over by Swedish kings, Russian tsars, and other European forces, with Peter the Great being the first out of the tsars to conquer the Baltic provinces. However, it's worth pointing out that during tsarist rule the German nobility had extensive autonomy as local Germans played an influential cultural role in the region.

Alex: Yeah, sadly the history of being caught between warring powers continued into modern history. But let’s mention the brief period between the two world wars when Estonians finally had their own state.

Alasdair: Well Estonia was under Russian rule until the Russian Revolution in 1917. The First World War changed things as Estonia gained full autonomy after the February Revolution, and the nation declared its independence in 1918. During this interwar period, Estonia made significant progress not only in a political sense but also in a cultural one – the Estonian language was promoted and in 1925 a law was passed which guaranteed minorities within Estonia the right to cultural autonomy, demonstrating a level of tolerance which was unusual in Europe at that time. However, this progress was thwarted by the Second World War. The Soviets occupied Estonia from 1940, the Nazis invaded and occupied from 1941-1944, and the Soviets reoccupied the country from 1944 until the USSR’s collapse in 1991.

Alex: It’s worth mentioning too that Estonia regained independence famously by a ‘Singing Revolution’ where the country sang en masse in Estonian by way of protest against Soviet rule.

Alasdair: Yes, Estonians do love a song. But for most of Estonia’s existence it has struggled for independence from competing European powers.

Alex: That’s right… but what has happened in Estonia since it gained independence in 1991?

Alasdair: Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Estonia’s future initially may have seemed bleak due to the country’s economic dependence on the USSR. However, Estonia made an impressively successful transition to democracy and a market economy. Estonia is one of the least corrupt countries in the world and it enjoys some of the highest living standards and a very high Human Development Index score.

News Item

Alex: Yes. So, one reason why Estonia is often in the news today is because, within the country, there are critical differences in opinion regarding issues such as history and relations with Russia and, like any other country in the western world, disagreements between the right and left, the elites and those left behind.

Alasdair: Well nowhere is perfect... An interesting story which came to light in 2019 across various news platforms was that Tallinn is the fastest segregating capital in Europe.

Alex: So this is the segregation between native Estonians and ethnic Russians who arrived largely during Soviet rule.

Alasdair: Very true. It’s not only an ‘ethnic’ issue though, but also a ‘class’ one. During Soviet times, Russian speaking groups enjoyed greater privileges than the native Estonians as the Soviet authorities imposed a strict policy of Russification of the country. Russian speakers lived in newer apartments with central heating and running water whereas most Estonians were confined to older pre-Soviet houses and residential buildings.

Alex: Right, and after the transition, former industrial and agricultural areas were at greater risk of falling behind which, today, has led to traditionally high unemployment in the North East where many native Russian speakers reside, but also rural poverty for many ethnic Estonians living elsewhere.

Alasdair: Exactly… It’s a very complicated issue, not solely based on ethnic differences, a legacy really of the Soviet Union’s annexation of the country in the 1940s which was mentioned earlier.

Alex: Yeah and in Tallinn tensions have escalated in the past, such as in 2007 after a Soviet monument was moved from the centre of the city to a military cemetery.

Alasdair: Yeah, Tallinn has an interesting demographic profile. Today Estonians make up roughly half of Tallinn’s population and the other half is made up predominantly of native Russian speakers. Before World War Two, Estonians made up more than 80% of their country’s capital. These changes show how Estonians were subject to ruthless policies by the Soviet regime which involved mass deportations and, in the north-east of the country especially, Russian workers migrated there in large numbers to work in heavy industry. Therefore, the Estonian government today has the challenge of trying to rebuild communities that were forged during Soviet times.

Alex: So, I guess the question is, how can the Estonian government resolve this issue?

Alasdair: One proposed initiative is to combat gentrification of Tallinn, as this

accentuates inequalities by having districts which are clearly more affluent

than others, which leads to lower social cohesion.

There are also efforts to ensure Estonians and those whose first language is Russian socialise more by increasing language learning and helping immigrant populations in general to gain access to different job markets and not be confined to what people call ‘low-skilled’ jobs. Although some progress has been made, relations between people living in Estonia are affected by tensions between Russia and Europe so it’s difficult to predict what will happen in the future.

Wrap up

Alex: The Russian question is definitely one to watch in Estonia, it will be key

to see how relations develop not only between Russian-speaking and ethnic Estonian citizens but between the two states themselves in the wider EU/NATO and Russia arena.

Alasdair: It certainly will, however, unfortunately that is all we have time for this week.

Thanks to everyone who tuned in and to Dr Allan Sikk and Dr Mart Kuldkepp

for being academic advisors for this episode.

Alex: Yes, thanks to them and thanks everyone, see you next time!

Alasdair: Yes, thanks everyone.

- Lithuania

Intro

*Short music intro*

Eleanor: Have you got any recommendations for what to drink for this episode?

Kristina: Yeah, I do have one recommendation – medus.

E: Ooh.

K: And that’s an interesting Lithuanian mead. You can make it with different spices, like thyme, lemon, cinnamon, cherries…

E: Wow that sounds fun. Cinnamon honey mead sounds very Christmassy.

K: It’s probably very suitable for winter.

**

K: Welcome to this episode of the Post-Soviet Press Pod’s “10 Minutes on…” series, where in each episode we focus on one of the 15 countries of the former Soviet Union, covering the essential basics as well as things like language, culture, history, and the biggest news stories affecting the country today – and we’ll be cramming it all into 10 minutes per episode! Your hosts today are me, Kristina Tsabala.

E: …And me, Eleanor Evans

K: Today we are going to be looking at Lithuania. And to get us through the whole episode we will be sampling some Lithuanian šakotis. It is a traditional spit cake which means that layers of batter are put on a rotating spit over an open fire.

E: The batter drops off the spit so makes little spikes. The cake ends up looking like a little Christmas tree! And it’s pretty tasty as well.

K: Yeah, I like it quite a lot. But let’s move onto the Basics.

*Short music intro*

Basics

K: So, Eleanor, give me the basics. Apart from how tasty spit cakes are, what does everyone need to know about Lithuania?

E: Lithuania is a country in the Baltics that has a coastline on the Baltic Sea. It borders Belarus, Poland, Russia and Latvia. The capital city is Vilnius, and the official language is Lithuanian. According to a study from 1989, a village north of Vilnius is positioned at the geographical centre of the European continent; there is even a monument showing exactly where it is.

K: The Lithuanian language is one of the two still-existing Baltic languages, the other being Latvian. Lithuanian is the second oldest language in Europe after the Basque language and it is so old that it contains words with Sanskrit origin. But it was not until the sixteenth century that a written language was developed.

E: Can you say something in Lithuanian? Do you have any words of wisdom?

K: Well, I can only try my best with the pronunciation but it's worth it. Lithuanians have two interesting ways of describing “lying”, as in not telling the truth. They say kabinti makaronus which literally translates as I will “hang pasta on the ears”. You can also say priburti which means that “I am casting a spell on you”.

E: I guess it’s the Lithuanian equivalent of “telling porkies”. On reflection, there seems to be a delicious coinciding of food and lying in both English and Lithuanian. Despite some interesting phrases, the Lithuanian language is a crucial cornerstone for the national identity of the country especially in the years when Lithuania was not independent.

Culture

E: Now, let's move on to culture, which unfortunately does not include more Lithuanian curse casting or pasta. An interesting fact is that a legendary rock and blues musician Bob Dylan, whose real name is Robert Zimmerman, has Lithuanian heritage. His mother’s grandparents were Lithuanian Jews who emigrated to the United States.

K: That is true! And there is another famous Lithuanian, but this time fictional: Hannibal Lecter from the famous movie Silence of the Lambs, the movie Anthony Hopkins won an Oscar for. The protagonist of the book by Thomas Harris is commemorated with a plaque in Vilnius.

E: That’s not the only plaque, there is a whole street in Vilnius commemorating authors and characters related to Lithuania.

K: So culturally speaking, the idea of Lithuanian national identity was promoted through literary works written in Lithuanian and by priests. One of the most influential priests and writers who promoted the Lithuanian language and dialects and culture is bishop Motiejus Valančius. In addition to his literary works, he was an active opposer of the ban on printing Lithuanian-language texts during the Russian empire and smuggled many books from Western Europe and sponsored the illegal printing of works in Lithuanian.

E: Priests seem to feature heavily in Lithuanian culture, as there is another influential priest from the twentieth century: Vincas Mykolaitis. His pen name was Putinas and he pioneered modern Lithuanian romance. His most famous novel In the Shadow of the Altars caused a scandal in Lithuania because it questioned priesthood and justified the rejection of it. It was controversial because the Catholic Church was and still is a very influential institution in Lithuania. Eventually, Putinas also renounced the priesthood.

K: One more famous poet and writer worth mentioning is Adam Mickiewicz, who is considered the Byron of Eastern Europe. He is famous for his poetic drama, Forefathers’ Eve and the epic poem Pan Tadeusz. He is also considered a national poet in Poland because he wrote in Polish, but he was born in the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania in a village in contemporary Belarus bordering contemporary Lithuania.

Well, we’re starting to touch on important historical figures, maybe we should contextualise them a bit. Lithuania might be a small country, but its history is very complex being at the intersection of East and West. So, where did it all start?

History

E: The first Lithuanian people were a tribe that was part of the Balts – a group of Indo-European people who spoke Baltic languages, many of which are now extinct but included what would later become Lithuanian and Latvian.

K: Unification of these lands as the Grand Duchy of Lithuania took place in the 1230s by Mindaugas who was later crowned the first Christian king of Lithuania.

E: Lithuania's Christian phase did not last long though as King Mindaugas was assassinated and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania became pagan again. It was not until the end of the 14th century that the Lithuanian ruling elite adopted Christianity after a union between Poland and Lithuania was established.

K: Lithuania and Poland cosying up will be a running theme in this section. By the end of the 14th century Lithuania was one of the biggest polities in Europe incorporating parts of modern-day Belarus, Ukraine, Poland and Russia. Though by the end of the 15th century Lithuania looked to Poland again, because the Grand Duchy of Moscow was threatening Lithuania.

E: And, for that reason, in the 16th century the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania established the Union of Lublin and these two polities became the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. It was one of the largest and most populous polities of 16th and 17th century Europe. It had a monarch who ruled both Lithuania and Poland, but what was impressive for that time was that the monarch was elected by the nobility (called the szlachta) who formed the legislature (called the sejm). The nobility had the liberum veto which gave members of the legislature the power to nullify any legislation. Some historians have called this system a precursor to democracy.

K: The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth implemented many reforms culminating in the Constitution of the 3rd May 1791. The constitution banned the liberum veto and is considered Europe's first constitution. However, independence did not last, as foreign powers moved to partition the Commonwealth into empires: the Habsburg Monarchy, Prussia, and the Russian Empire. Most of Lithuanian territory went to the Russian Empire.

After unsuccessful uprisings in the 19th century, the Russian Empire implemented many Russification policies. Increased repression also led to the Lithuanian National Revival which included the desire to re-establish an independent Lithuanian state.

E: Though they had to wait for an independent Lithuania for a while. Independence of Lithuania was declared in 1918 with a state governed by democratic principles, including women’s suffrage, worker’s rights and land reforms. The state lasted until 1940.

K: Independence was short-lived because in WWII as part of the non-aggression alliance between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, Lithuania was transferred to the Soviet sphere of influence. This ultimately led to the invasion of Lithuania by the Soviet Union on 15th June 1940.

It wasn’t until 11th March 1990 that the Supreme Council of Lithuania declared the restoration of independence from the Soviet Union, the first Soviet-occupied state to announce independence.