News 2020

Booking for Slade Short Courses Now Open

Our Short Course Programme is going online! Bookings are now open for Drawing on Tuesday evenings, starting in January, and two 4-week Saturday Drawing courses starting in January and February. For further details see our Short Courses page.

Alvaro Barrington interview for UCL Students' Union

Watch Alvaro Barrington speak about his practice and experience studying as a graduate at the Slade with Students Union UCL on YouTube: https://youtu.be/B1rijdE2bGo (Alvaro's interview is 44mins in).

Beacon Bursaries - UCL Public Engagement

Many congratulations to Jo Guile and Thomas Morgan Evans, who have both been awarded 2020 UCL Beacon Bursaries for public engagement projects.

Red, Green, Blue, East: Jo Guile and Dr Emily Patterson

Emily and Jo have co-designed a series of workshops with Into Focus, an East London charity-funded organisation specialising in photography. They will be running these workshops, which explore the science, art, and experience of colour within Tower Hamlets. The project has developed through a collaboration that was formed during UCL Culture’s Trellis programme and will culminate with a public art exhibition.

Dr Emily Patterson is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Ophthalmology and Jo Guile is an Artist and Technician at the Slade School of Fine Art.

Concrete Canvas: Thomas Morgan Evans

Through this bursary, Thomas will fund 10 weekly four-hour sessions for children and young people from and around the D’Eynsford Estate in south east London. They will work with a community artist and UCL MA and PhD students to assist in creating a public art work on the basketball court, taking part in learning exercises inspired by the mural painting that is currently taking place and discussing its design. The project aims to support and encourage community home learning and physical activity for local young people, in response to the changes to day-to-day living caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Dr Thomas Morgan Evans is a teaching fellow at the Slade School of Fine Art.

See UCL Culture's page for more information about Beacon Bursaries.

Bloomberg New Contemporaries 2020 - South London Gallery

Liam Mertens, Kikie Minobe, Anna-Rose Stefatou and Orfeo O’Leary Tagiuri are showing in Bloomberg New Contemporaries 2020, at South London Gallery, 65–67 Peckham Road, London SE5 8UH, from 13 January - 7 March 2021. See https://newcontemporaries.org.uk/exhibitions-and-events/exhibitions/bloomberg-new-contemporaries-2020-south-london-gallery.

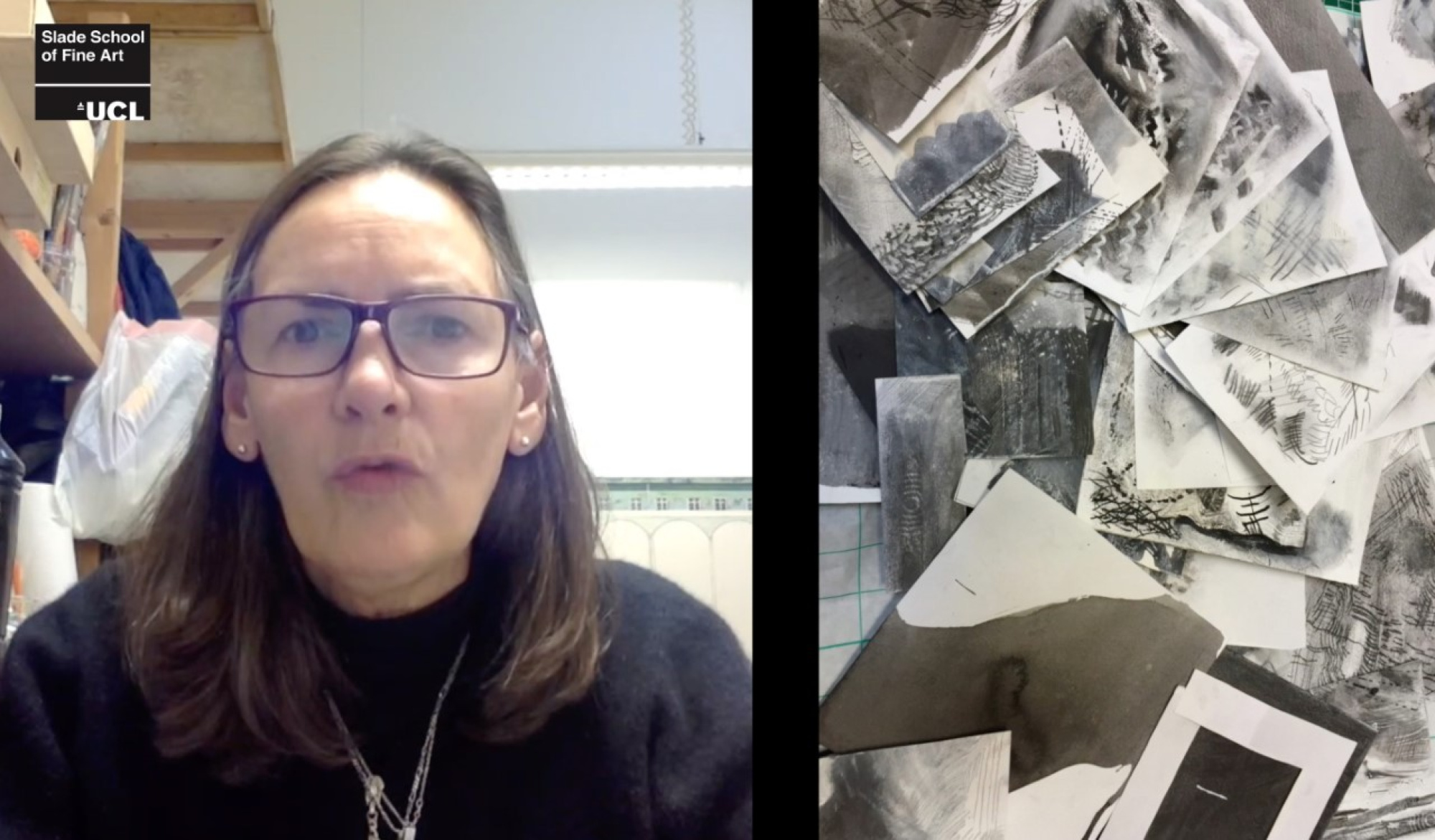

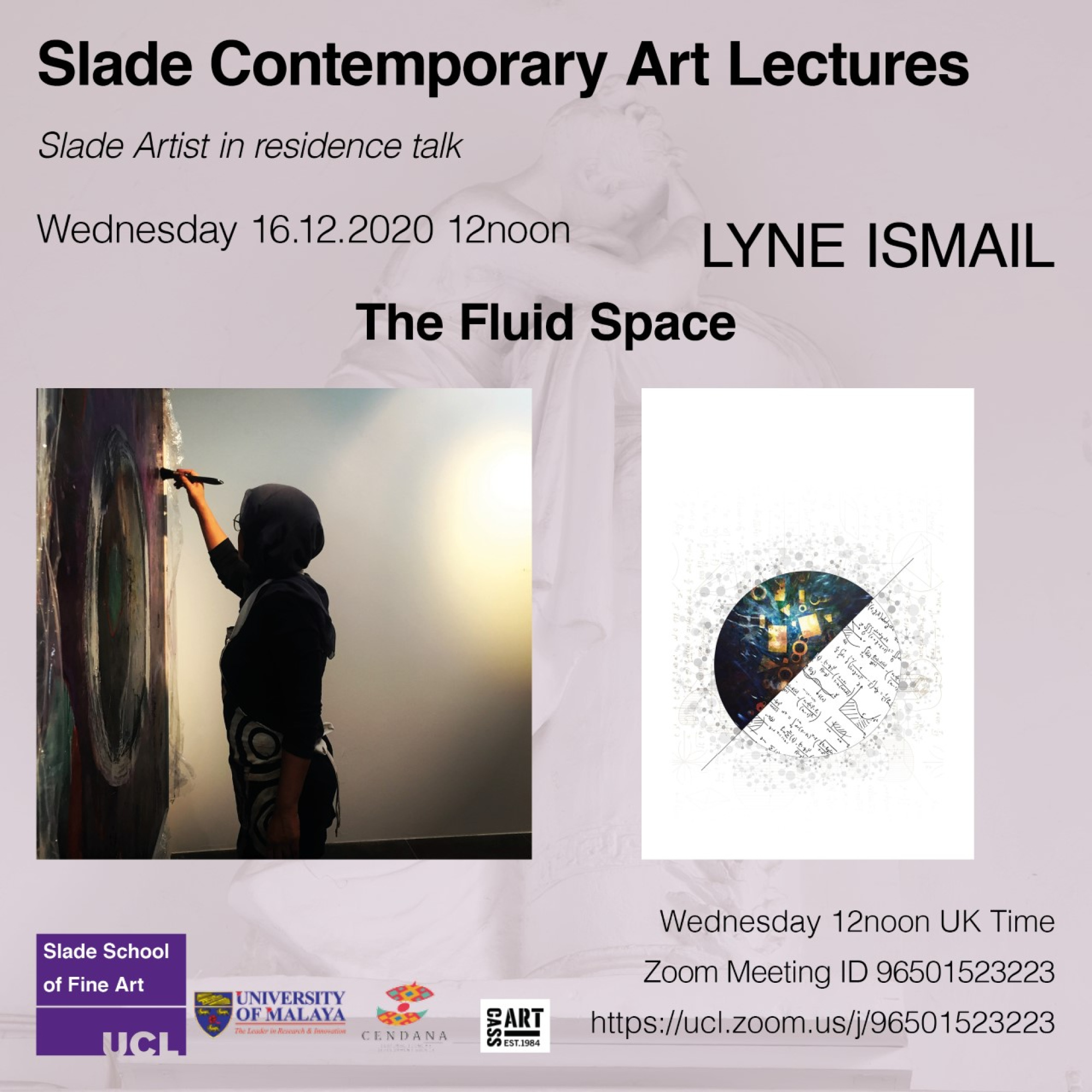

Contemporary Art Lecture with Lyne Ismail

The Fluid Space: Contemporary Art Lecture with Slade Artist-in-Residence Lyne Ismail, Wednesday 16 December, 12noon (GMT). Via Zoom: https://ucl.zoom.us/j/96501523223.

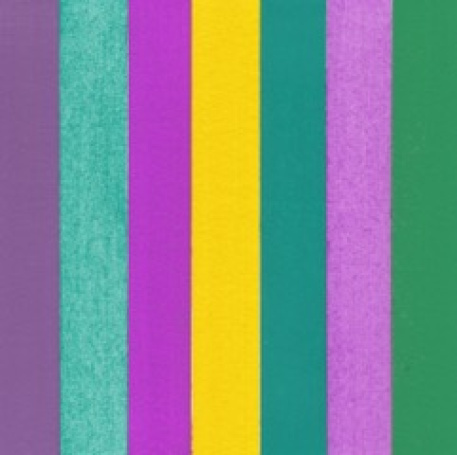

A Colour A Day: Week 38 - 7 - 13 December

Each pigment is bound in gum Arabic on W&N watercolour paper and read from left to right:Cobalt Violet DarkCobalt GreenCobalt Violet BrilliantCobalt Yellow PaleCobalt Green BluishCobalt Violet Cobalt Titanate Green

A Colour A Day

Week 38, 7 - 13 December 2020

Follow Jo Volley's A Colour a Day project, a year-long project to celebrate one colour each day by recording a swatch of it, on The Pigment Timeline Blog: https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/pigment-timeline .

This week’s colours are accompanied with a text by Robert Mead in response to the cobalts.

Cobalt: Pigment of Hope and Destruction

Robert Mead

Cobalt shares an entwined history with both painting and technology. The mineral is capable of producing a range of different colours - perhaps the most commonly known is Cobalt Blue. This is a cobalt aluminate pigment and was first discovered in 1775 – with further modern production achieved in 1777, where the moistening of aluminium compounds with a cobalt solution turned blue and strongly calcined.

A variety of other colours can be produced through cobalt; a range of violets can be created through a variety of different compounds – such as cobalt magnesium arsenate – and cobalt phosphate octahydrate. Cobalt Green has been made by multiple processes including the direct mixture of cobalt blue with ‘chromic’ yellow or a combination of cobalt and zinc or iron oxide. Cobalt Yellow is a potassium cobalt nitrate, first synthesised in 1831 – through the reaction between potassium nitrite and cobalt salts, creating a crystalline mass.

Using cobalt, we are able to produce range of wonderful and unique colours. However, as a mineral its demand has increased alongside the development of new technologies – as a key component of batteries in laptops, phones and increasingly electric cars. The main source of cobalt extraction is in The Democratic Republic of Congo, whose history of colonisation by Belgium from 1869–1908 through to its independence in the 1960s is entwined with the desire for its available supply of minerals such as diamonds, copper and uranium. Now major western companies such as Apple, Dell and Microsoft have bought into the mining industry there, as cobalt suppliers for their lithium batteries, this high demand has led to quarries operating with dangerous conditions and often using child labour.

Furthermore, both the pigment and the mineral itself hold highly toxic particles and when consumed or inhaled and can cause major health risk - increased through poor mining conditions. Further increasing the demand for cobalt is the development of electric cars. As we attempt to offset the climate crisis by moving to using electric vehicles, companies such as BMW and Tesla have also invested heavily in cobalt mining to acquire the material for powering them. In this case, cobalt is at the centre of paradox between hope for moving away from fossil fuels and towards clean electric energy and the negative consequences its acquisition results in.

Without sustainable mining methods, its production is tainted by this problematic discord.In reflecting on cobalt’s significance for our future, it seems prescient that it was the key ingredient in what was considered the doomsday weapon of the Cold War – the Cobalt Bomb (or C-Bomb), theoretically capable of wiping out all human life on the planet and featuring in films such as Beneath the Planet of the Apes and Dr Strangelove. The use of cobalt would allow a much higher level of fallout to be released from detonation, many times greater than the level of residual radiation still present in the strata of the Earth from the era of nuclear testing.

When we look at the alluring colours it can produce we can also consider that cobalt pigments are entwined with both our colonial and technological history and humanities attempts at both healing and destruction.

Robert Mead is a painter and PhD researcher at the Slade School of Fine Art. The aim of his research is to make paintings that form emotive connections between the viewer and our environment which draw them into wider hidden discourses. Robert says of his work; 'Moving through the strata of my paintings digs up histories and ghosts that we may not wish to confront but are bound to our past’ .

Each pigment is bound in gum Arabic on W&N watercolour paper and read from left to right:

Cobalt Violet Dark

Cobalt Green

Cobalt Violet Brilliant

Cobalt Yellow Pale

Cobalt Green Bluish

Cobalt Violet

Cobalt Titanate Green

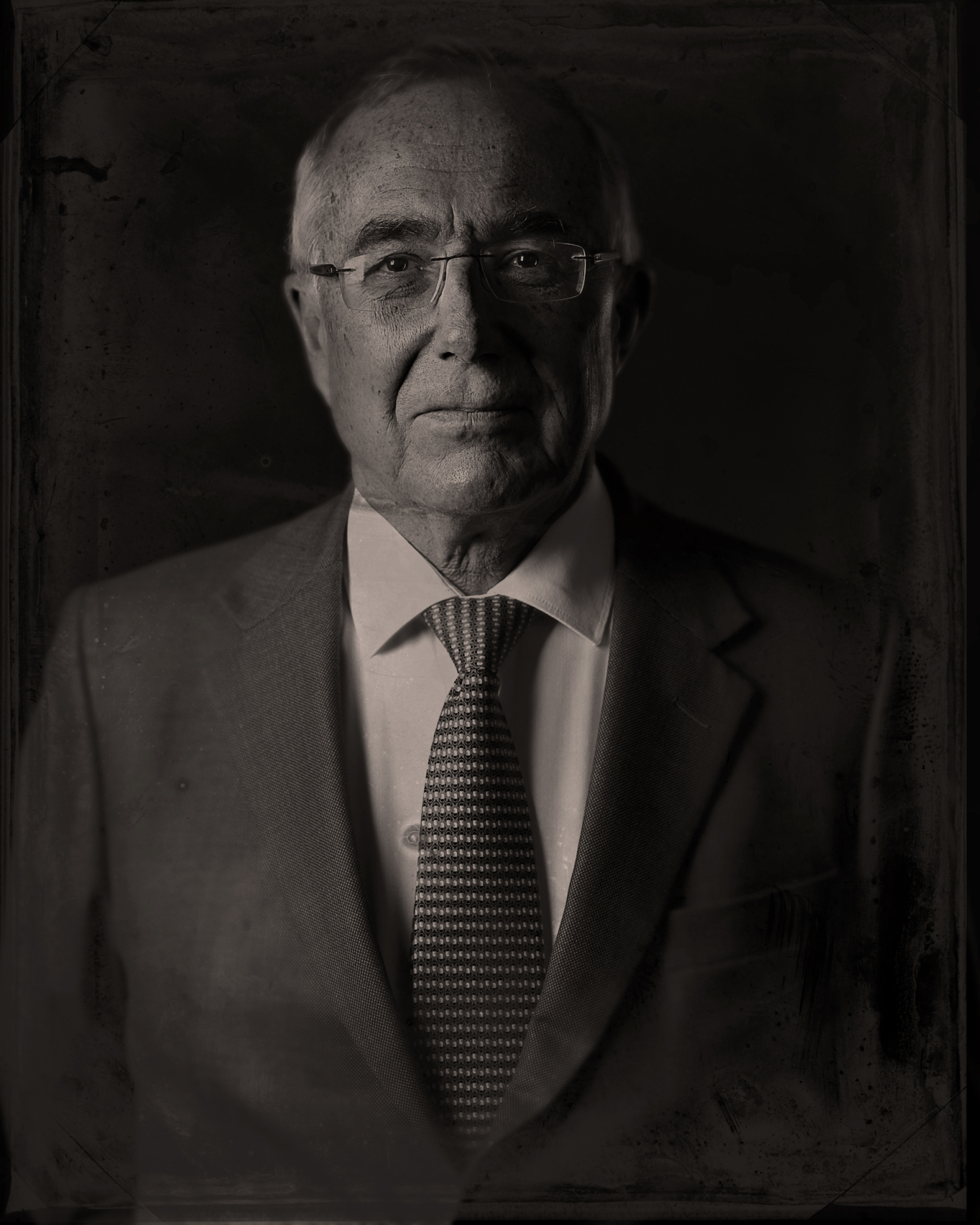

Ellis Parkinson wins Provost Portrait Competition

Ellis Parkinson Provost Portait Competition winner 2020

UCL’s current President & Provost Professor Michael Arthur will be stepping down from the role at the end of this month after seven years. To commemorate the end of UCL Provost Michael Arthur's term of office and as a record of his leadership, one of UCL’s distinguished Hong Kong alumni, Vincent Cheung, generously sponsored the Slade School of Fine Art to offer a photographic portrait of the Provost as a gift.

Ellis gave a short interview about the commission and his approach.

What is the concept behind the commission?

When considering the brief of this task, I thought a lot about where we are today as individuals. How quickly things can change, how important our individual actions are and can be, as well as how significant of a moment we find ourselves in, socially and politically. I thought about a number of processes that I felt reflected this feeling and the one I considered the best is that of Tintype Photography. I wanted to counter the impermanence and uncertainty of our current moment with something tangible, with something that will last for generations to come. Today the Tintype is considered a non-standard method by which to capture photos, but their fine quality and rich history speak exactly to an aesthetic which I consider the model for a situation such as commemorating the proverbial changing of the UCL guard. The Tintype is an honest method of photographic production; it refuses to glaze over imperfections and bares all to the world, something that I feel is very important not just in terms of the current moment, but also when evaluating prominent figures within an institution such as UCL.

Can you tell us about the photography technique you are using?

The creation of a Tintype is a highly unpredictable process; the slightest chemical imbalance, light exposure or miscalculation can destroy the photo, which under normal circumstances is lost permanently. A Tintype Photograph is taken in multiple stages. The first is to coat a sheet of metal, most commonly 4x5 inches or 8x10 inches, in Collodion emulsion. This part of the process is usually done in a darkroom as the emulsion is light sensitive and the sheet is placed in a sleeve so that no unwanted light is able to reach the plate. The plate is then loaded into the photographic bellows. Next, the shot is choreographed and appropriately lit. Collodion has a very low ISO, so lighting will be key when the photo is taken. Once the shutter is hit, the subject is flooded with light and the photographic portion of the process is over. The plate is then encased in its sleeve and returned to the darkroom. Afterwards, it is coated in a developer keyed to the emulsion’s ISO until the negative image begins to reveal itself. The solution is then washed off to prevent overexposure and submerged in a liquid fixative under direct UV light, and with that, you have a fully formed Tintype photograph. The Tintype is a photographic process that has a particularly prolific and diverse history, some of which UCL itself is directly entangled in. I felt that by conducting a portrait in this way, I am fully embodying the UCL verbage of ‘Understanding the Past, Challenging the Present and Shaping the Future’.

How does this commission relate to your art practice?

First and foremost, my practice is formed around creating outcomes that I have a personal interest and attachment to, the defining factor here being the opportunity to create a piece reflective of historical methods of artistic production in a modern setting. Whilst researching the Tintype process I became enamored with its history, and the multicultural view it presented me of America in the 1800s. In a time that the media would have you believe was dominated by white leaders and figures of significance, I saw black and native American men, women and children who contributed just as much to the construction, image and aesthetic of the period as anybody else. The history of the Tintype is representative of a multicultural inclusion that has been overwritten and should be celebrated, rather than forgotten. Something that I have always maintained within my practice is a diverse and eclectic portfolio that is fueled by continual experimentation and pushing of the boundaries – visually, practically and ideologically. Experimentation is one of the core tenets of my practice. As well as this, much of my working practice whilst I have been a student here has revolved around deconstructing institutional barriers and being able to interact with someone at the apex of our academic structure will surely inform this aspect of my working practice.

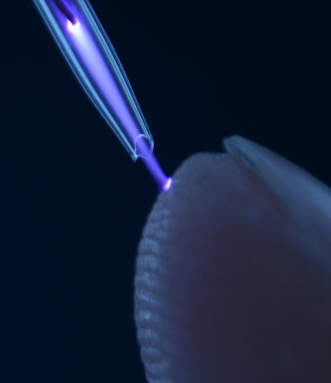

Slade Scientist in Residence 2021 - Professor Daren Caruana

Slade Scientist in Residence 2021

We are delighted to announce that Professor Daren Caruana, UCL Chemistry will be the 2021 Slade Scientist in Residence.

Statement from Professor Daren Caruana:

I am incredibly excited about this residency at the Slade School. Science has been my career but art has always been a firm passion of mine.

I originally identified as a biochemist and really enjoyed the interrogation of chemical systems within a biological setting. Over the course of my training, I was fortunate to have been exposed to the scientific process in several fields of research; eventually I landed as a physical chemist, or more specifically electrochemist. Electrochemistry is quite an important discipline that underpins many important technological applications, such as batteries and power sources, electroplating, sensing, and many more. My research focuses on ‘blue skies’ and less applied areas which often has no clear end use. Since I have been at UCL, I have been concerned with understanding gaseous plasmas, an area of research with is quite unique. The rationale behind this work is to investigate the properties of these fascinating electrically conducting gases, using an electrochemical approach. The presence of free electrons opens up the possibility of observing and possibly controlling very unusual chemical reactions. Electrons are normally discretely organised within atoms and molecules, however, if the conditions are favourable electrons tend to exchange between molecules or reorganise within molecules; this is the basis of almost all chemical change. In plasmas electrons exist freely in the gas phase and it turns out they can react in quite unique ways. So, I think of electrons as reagents or reactive chemical species rather than a consequential component of chemical change. Accidently, this work has led to the development of some useful technology which has resulted in a patent, centred on plasma jet materials synthesis. Of course, another benefit is the fact that these plasmas are beautiful to work with. There is something quite satisfying working with a hot ball of glowing gas!

|  |

| Butane flame with additives, photo credit: Matt Li | Argon plasma jet, photo credit: M. Emre Sener |

In the early stages of my career, I was a great fan of ‘Lateral thinking’, a way of thinking developed by Edward De Bono. Originally aimed at business and economic theory, it can be applied to many areas, and I would say that it shaped a lot of my research approach, particularly the way I think of ideas and exploring problems. The approach I adopt in my research is a lot of fun and very satisfying; although can sometimes lead into blind alleys; the difficulty is actually recognising this! I don’t often question the scientific approach, but it is probably about time I did. I am hoping this residency will give me the space to dissect my scientific approach and explore the parallels with the artistic approach.

Art has always been important in my life; I turn to oil painting whenever I have the time or life throws a pandemic. So, an opportunity to be involved with the Slade is an extraordinary opportunity for me personally. The shape of this residency will hopefully be symbiotic, a chance for me to study and learn, but if appropriate, contribute to various projects in the Slade. I look forward to step completely out of my comfort zone, be privileged for a chance to observe and appreciate the philosophy behind the creative process. With my chemistry hat on, I would like to explore how art practice uses chemistry and start to examine how the different facets of chemistry can play a role in the creative process or in the artwork itself. Although this residency will be for a short period, I hope to act a conduit between the Slade and the chemistry department for years to come.

Slade Undergraduate Admissions Q&A

Find out about our BA/BFA Fine Art at Slade Undergraduate Admissions Live Q&A, your chance to ask a panel of Slade Undergraduate tutors about our BA/BFA and how to apply on Thursday 17 December at either 2 - 2.45pm GMT or 6 - 6.45pm GMT.

Info and booking: https://ucl.ac.uk/slade/degrees/slade-undergraduate-admissions-liveq_a

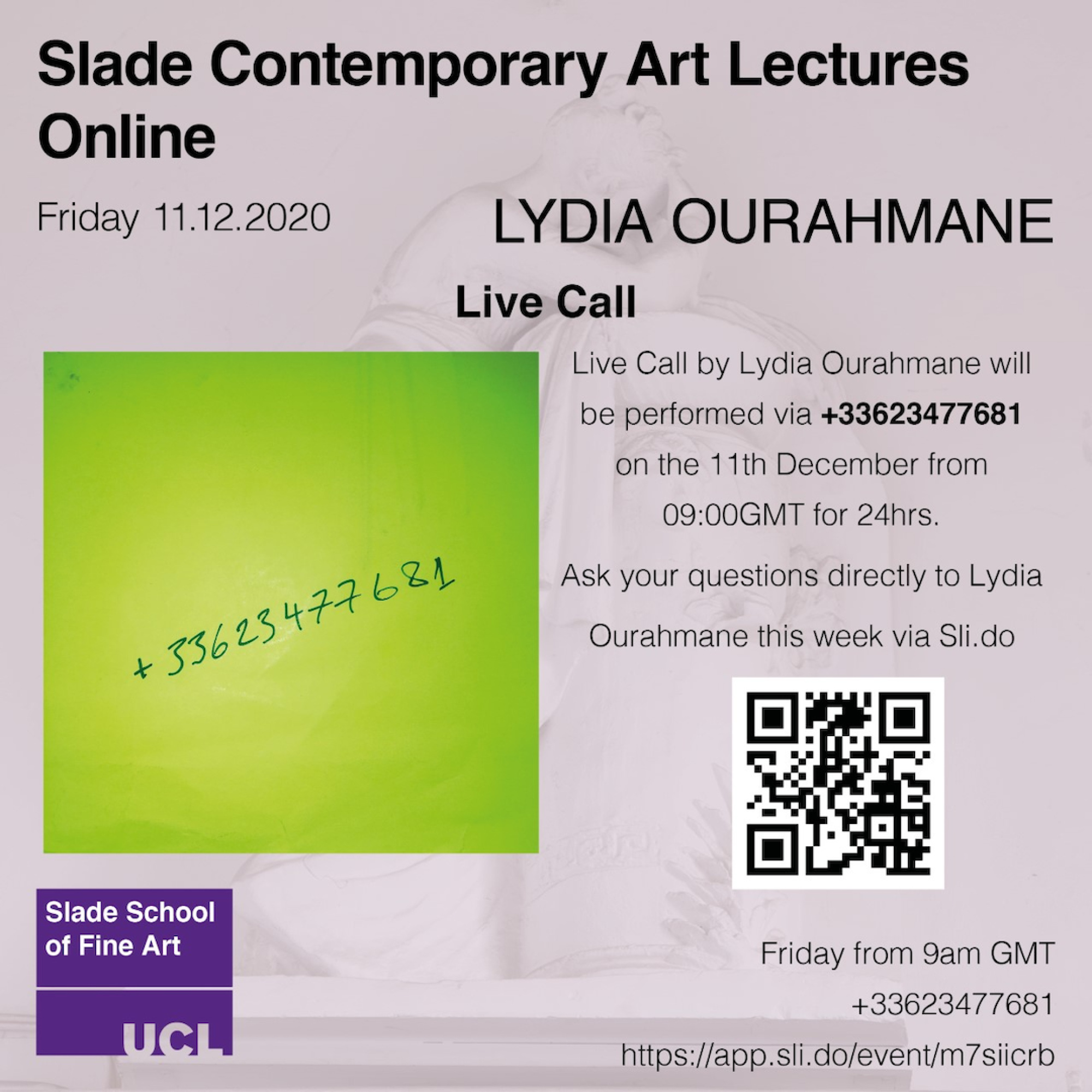

Contemporary Art Lecture: Live Call - Lydia Ourahmane

Live Call by Lydia Ourahmane will be performed via +33623477681 on the 11 December from 09:00GMT for 24hrs. For more details, see https://www.ucl.ac.uk/slade/events/lydia-ourahmane

Launch Six Bells Red

Arved Colvin-Smith

Onya McCausland launches (online and with a physical presence at Six Bells Mine Water Treatment Scheme in Wales) the first colour in the range called ‘Six Bells Red’ on Friday 11 December at 12noon. Join on Zoom: https://ucl.zoom.us/j/92082269256. To find out more about her research, see the turninglandscape.com website.

Onya McCausland, an artist graduated from UCL Slade School of Fine Art, has produced the first ever exterior / interior grade mineral based emulsion wall paint made from 100% waste ochre materials. Onya has also created a collection of paintings called ‘Colour From The Mines’ (see here for details https://onyamccausland.com/ucl/ and https://onyamccausland.com/europe/

Friday 11th December sees the launch (online and with a physical presence at Six Bells Mine Water Treatment Scheme in Wales) of the first colour in the range called ‘Six Bells Red’.

- Six Bells Red is a first edition. It has been specially created - burnt at a specific temperature - and thereby producing a limited amount of this particular pigment.

- This will be a special limited edition of 100 one litre tins. Up to 50 tins will be given to the public and organisations across Gwent for the opportunity to participate in the project by painting buildings, houses, doors, gates and walls.

- In addition, 1,000 tubes of artists’ oil paint named ‘Six Bells Burnt Ochre’ (each with its own individual serial number) will be made available for sale at www.turninglandscape.com, retailing for £25. All proceeds from Turning Landscape CIC (Community Interest Company) sales will be recycled back into the project to fund more paint creation - alongside an art education programme at Six Bells.

- A cast iron plaque with a map of the site will be installed at the site, marking it as the source of the paint. The plaque will be visible from the footpath at the far north end of the perimeter fence.

Onya McCausland, who developed the idea of turning recycled coal mine sludge into paint while studying for her PhD at the Slade, visited mine sites across former British coalfield locations in South Wales, Scotland, Lancashire and Yorkshire.

Onya travelled around the country collecting samples of ochre to take back to a UCL laboratory and her studio where through painting, she discovered striking differences between the colours depending on their geographic location.

Onya's practice develops an original and innovative approach to the role of the art object by making paint - including integrating its site of formation - as an artwork, that is co-produced with manufacturers and members of the local ex-mining community. Paint in tubes and tins are considered as ‘art objects’ or editioned prints for distribution and use by the community. Onya wants to encourage individuals and organisations to take up using this paint as part of a collective multi part public artwork next year. It will be free to local residents on application.

Onya McCausland said, "The mine water treatment schemes are the really important link between the colour, the material and the place. They reflect an important part of Britain’s cultural, social and industrial history and legacy.”

The project has been funded by the Leverhulme Trust, the Slade School of Fine Art and UCLI&E, a group of specialists at UCL who help its academics and students turn their ideas into reality.

UCLI&E help has included guidance and advice as well as funding from its Knowledge Exchange Fund. UCLI&E support has also enabled the commercialisation of the paints and engagement of local communities to help bring the initiative to life. It has also been supported by Michael Harding Paints.

Mirror of Impalpable Nudity - Gao

Barbara Wesolowska is showing in Mirror of Implapable Nudity re-opens at Gao Gallery, Unit 7, 88 Mile End Rd, London E1 4UN, until 15 January 2021. For information see: http://www.gao.gallery/mirror-of-impalpable-nudity.

Gleaners: Olivia Bax & Hannah Hughes - Sid Motion

Gleaners: Olivia Bax & Hannah Hughes is showing at Sid Motion, 24a Penarth Centre, Hatcham Road, SE15 1TR, from 5 November 2020 - 18 January 2021. By appointment only: https://www.sidmotiongallery.co.uk.

A Dream Of A Real Memory - Piccadilly Lights

Eddie Peake’s A Dream Of A Real Memory replaces the adverts on Piccadilly Circus' screen every evening in December at 8:20pm - 8:22pm. For further information see the Circa Art website.

Slade Graduate Admissions Live Q&A

In place of our usual Slade MA/MFA Open Days we will be holding two live Q&As live online via Zoom as follows (reserve a place via Eventbrite by clicking on your chosen date):

Wednesday 9 December 2020, 6:00 - 6:45pm (GMT)

Tuesday 15 December 2020, 12noon - 12:45pm (GMT)

For further information, see our Graduate Admissions Live Q&A page.

Correspondences - Frestonian Gallery

Tess Jaray and Paul de Monchaux are showing in Correspondences at Frestonian Gallery, 2 Olaf Street, London W11 4BE, from 3 December 2020 - 9 January 2021. See the Frestonian Gallery website.

Adham Faramawy - Skin Flick

Adham Faramawy's Skin Flick, is online until 7 December on Vdrome as part of Serpentine Gallery's The Shape of a Circle in the Mind of a Fish: The Understory of the Understory art and ecology festival, 5 - 6 December 2020.

Studio Audio - PEER

Listen to works by Phyllida Barlow and Jadé Fadojutimi on PEER's Studio Audio podcast free until 31 December 2020.See https://www.peeruk.org/studioaudio

Nick Hornby: Zygotes and Confessions - Mostyn Gallery

Nick Hornby: Zygotes and Confessions is showing at Mostyn Gallery, 12 Vaughan Street

Llandudno LL30 1AB, from 14 November - 18 April 2021. See the Mostyn website for further information.

Applications open for graduate study

Applications for the Slade School of Fine Art Postgraduate programme (MA/MFA) are open.

Deadlines:

Written application: 5 Jan 2021

Portfolio deadline: All portfolios must be submitted electronically 11.59pm (GMT) on Friday, 15 January 2021

For further information, see: https://ucl.ac.uk/slade/degrees/ma-mfa#admissions