Opinion: Work-life balance in a pandemic is a public health issue we cannot ignore

26 February 2021

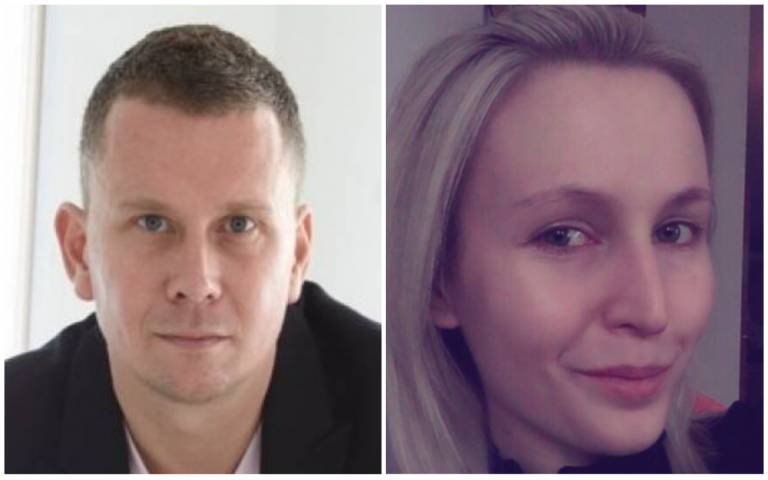

Despite fears that home working would lead to a decrease in productivity, evidence shows that people have worked more, not less, during the Covid-19 pandemic, write PhD researcher Dave Cook (UCL Anthropology) and Research Fellow Anna Rudnicka (UCL Interaction Centre).

Before the pandemic, a common objection to remote working was the suspicion that staff would disengage and productivity levels would drop. But recent evidence suggests the opposite is true – working from home effectively means working more. In the UK, for example, many employees are reportedly putting in an extra two hours a day. It’s even longer in the US.

Our survey also indicates that feeling fortunate to still be in work, the collapse of work-life boundaries, and the fear of being under surveillance from employers, have all led to people working harder for longer.

Those juggling work and caring responsibilities are often struggling the most. A recent UK poll showed 71% of working mothers who requested furlough to look after their children were refused. The “sandwich generation”, those managing childcare and caring for older relatives, are also having a hard time.

These factors all point to a future where overwork is normalised and work-life balance becomes nothing more than an aspiration. We must not allow this to happen.

But what is work-life balance precisely? It is a term so frequently dropped into conversation that it can sound vague and open to interpretation. According to Anna Cox, a professor of human-computer interaction at UCL, it means “feeling in control of how you balance the various demands of all aspects of life to enable wellbeing and avoid illness”. It should involve “happiness, fulfilment and job satisfaction”.

She adds: “Just because we can be connected to work all the time, doesn’t mean we should be. Policymakers need to take concrete action to protect workers’ rights to switch off.”

Another disturbing trend that makes switching off so difficult is the emergence of so-called “bossware”, controversial software that some companies use to monitor employees, under the guise of “productivity enhancement”. In November 2020, there was uproar following reports that even Microsoft 365 gave bosses the ability to measure email activity and the use of shared documents.

Bossware – even the fear of it – encourages a culture of overwork. In our survey of 500 UK workers, respondents told us of their concerns over privacy during video calls, regularly interrupted personal time and the constant pinging of work notifications. One worker explained: “If I leave at 12.30 for a lunchtime walk, and later see my boss messaged me on Slack at 12.35, my heart sinks.”

Take a break

Our work, as part of the eWorkLife project, also included in-depth interviews to investigate the transition to remote working. Another finding was that social norms around taking breaks from work – a colleague inviting you out for coffee or lunch – are vanishing. Expectations for workers to be available 24/7 were accelerating before the pandemic and, unchecked, they will become the norm.

It is vital to establish flexible social rituals around taking short breaks throughout the workday. But workers will gradually lose these healthy habits unless companies create work cultures and clear policies that encourage staff to take breaks. The government needs to take action to tackle these rapid social shifts, which should not be left to individual workers to navigate.

And although some companies are leading the way by regularly surveying employees, this is not the norm. Instead, trade unions are publishing research and pressing for change. (White-collar workers might feel joining a union is stigmatising, yet the pandemic has shown that any job can be precarious.) And when high-profile bosses talk of workers “playing the victim card” it’s little wonder staff feel voiceless.

The immediate policy response should be to temporarily force companies to accept furlough requests for those with caring responsibilities. Companies should also be strongly encouraged to update or publish flexible working policies.

Shockingly, 60% of US companies still haven’t shared their remote working policies, and workers at all levels have had enough of inaction. One executive who quit due to spiralling workload confided to us: “Sure, employers are under huge pressure to survive this pandemic. But asking staff to carry the brunt through inhuman productivity rates is unsustainable.”

A change of approach is essential. Since the arrival of the pandemic, large numbers of people are working longer and harder. And even with increased rates of vaccination, home working in some form is surely here to stay. Ensuring it continues in a balanced way should not a responsibility that rests entirely on individuals.

The EU is now rightly urging its member states to implement policies that support work-life balance and the right to disconnect, and the eWorkLife project is urging the UK Government to take similar steps.

Achieving a work-life balance is not just a worthwhile goal – it is an essential one. It is vital for mental health, physical health, and long-term economic success – and a task at which governments and businesses should be working much harder.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation on 26 February 2021.

Links

- Original article in The Conversation

- PhD Researcher Dave Cook’s academic profile

- Research Fellow Anna Rudnicka’s academic profile

- UCL Anthropology

- UCL Faculty of Social & Historical Sciences

- UCL Interaction Centre

- UCL Psychology & Language Sciences

- UCL Faculty of Brain Sciences

Close

Close