S2 Ep1: Touch

MORE ON THE STORIES

TRANSCRIPT

SUMMARY KEYWORDS

touch, people, prosthetics, ucl, touching, volunteering, students, research, sensations, understand, objects, home, participants, pandemic, electronic, uk, lesson, materials, building, hand

SPEAKERS

Cassidy Martin, Lili Golmohammadi, Carey Jewitt, Alessia Qiu, Helge Wurdemann

Cassidy Martin 00:02

Hello, I'm Cassidy and welcome to the first episode of the second series of made at UCL, the podcast. This podcast is for anyone who has ever wondered why what goes on at universities matter. from academia to community outreach, we want to give you insight into why researchers and volunteers at UCL are so passionate about what they do, and how what they do helps to make this world a better place. Each episode includes three stories with one common theme. And today's theme, is Touch.

Lili Golmohammadi 00:37

Touch is a very powerful form of communication,

Alessia Qiu 00:44

which is very important for how we bond with people. I think staying in touch can be very simple, and sometimes

Helge Wurdemann 00:53

is the physical interaction with the environment and the information that you would receive the

Lili Golmohammadi 01:00

sense through which we understand the world when we're born. And then it's the

Carey Jewitt 01:04

last, we find out information about the world through touch the ways we touch on

Helge Wurdemann 01:08

it. Or we grasp items, we want to experience how much we exert to an object because we don't want to squeeze it.

Lili Golmohammadi 01:16

The so much research that's very, very clearly showing that it's really important for our well being and development.

Cassidy Martin 01:25

This month's episode is all about touch, from touching to not touching to how we stay in touch right now. Over the past year, touch has become something we probably all think about a little more than we ever had before. I know I'm grateful for things that help us to stay in touch, like zoom, where we can still meet people face to face in a way. But like all of us, I'm sure I missed certain kinds of touch, like a nice warm hug from a friend, or even all those little sensations of touch, like when you're on a crowded dance floor and dancing up close to someone you fancy. All of our guests this month are working in areas related to touch, specifically, digital touch, keeping in touch and the sensation of touch. To begin our journey into touch. I sat down with Lily and her PhD supervisor Professor Carrie Jewett from the intach projects at UCL.

Lili Golmohammadi 02:27

In touches, the five year projects exploring emerging digital touch technologies across lots of different realms.

Cassidy Martin 02:35

This research is part of

Carey Jewitt 02:36

the UCL knowledge lab, which is in the Department of Culture, Communication and Media and the faculty of the Institute of Education.

Cassidy Martin 02:45

Lily and Carrie don't just study any kind of touch. Their work, especially recently has focused on digital touch.

Carey Jewitt 02:53

Digital touch is touch that's been remediated through technology. So our project isn't looking at touch screens, were looking at advanced technologies like robotics, virtual reality, augmented reality, bio sensing, and wearable technologies. And were asking how touches getting brought into those advanced technological landscapes in the context of communication. The

Cassidy Martin 03:23

first problem that legally and Carrie had to solve through their research was how to even study touch.

Carey Jewitt 03:30

Some of the worst interviews I've ever done in my research career, have been trying to ask people about touch.

Cassidy Martin 03:36

It sounds kind of simple asking people about their experiences of touch.

Carey Jewitt 03:41

We did a study in the Natural History Museum and one of their galleries that has touch objects, me and my colleague, Sarah price, people were exploring these objects and making lots of kind of connections with memories and lots of imagination.

Cassidy Martin 03:56

But even though we all use our sense of touch every day, it's one of those things we rarely have to stop and think about.

Carey Jewitt 04:04

And then people would come out the gallery we do an interview with them and say, you know, we saw how you were touching this particular object. And what does that mean to you?

Cassidy Martin 04:13

It's certainly something that we rarely have to describe or explain to someone, people

Carey Jewitt 04:18

just couldn't talk about it. The language of descriptions talk about it, but they also didn't really think about it when they were doing it.

Cassidy Martin 04:27

And that's because touch is complicated.

Carey Jewitt 04:30

So there's these different kinds of layers of touch and there's touch with objects is touch with others is touch with yourself and there's touch with the environment. When we walk along the beach, without our shoes on and we feel the warmth of the sand and you feel the water on you. We feel the wind on you or the rain. We can think about those things as touch as well.

Cassidy Martin 04:56

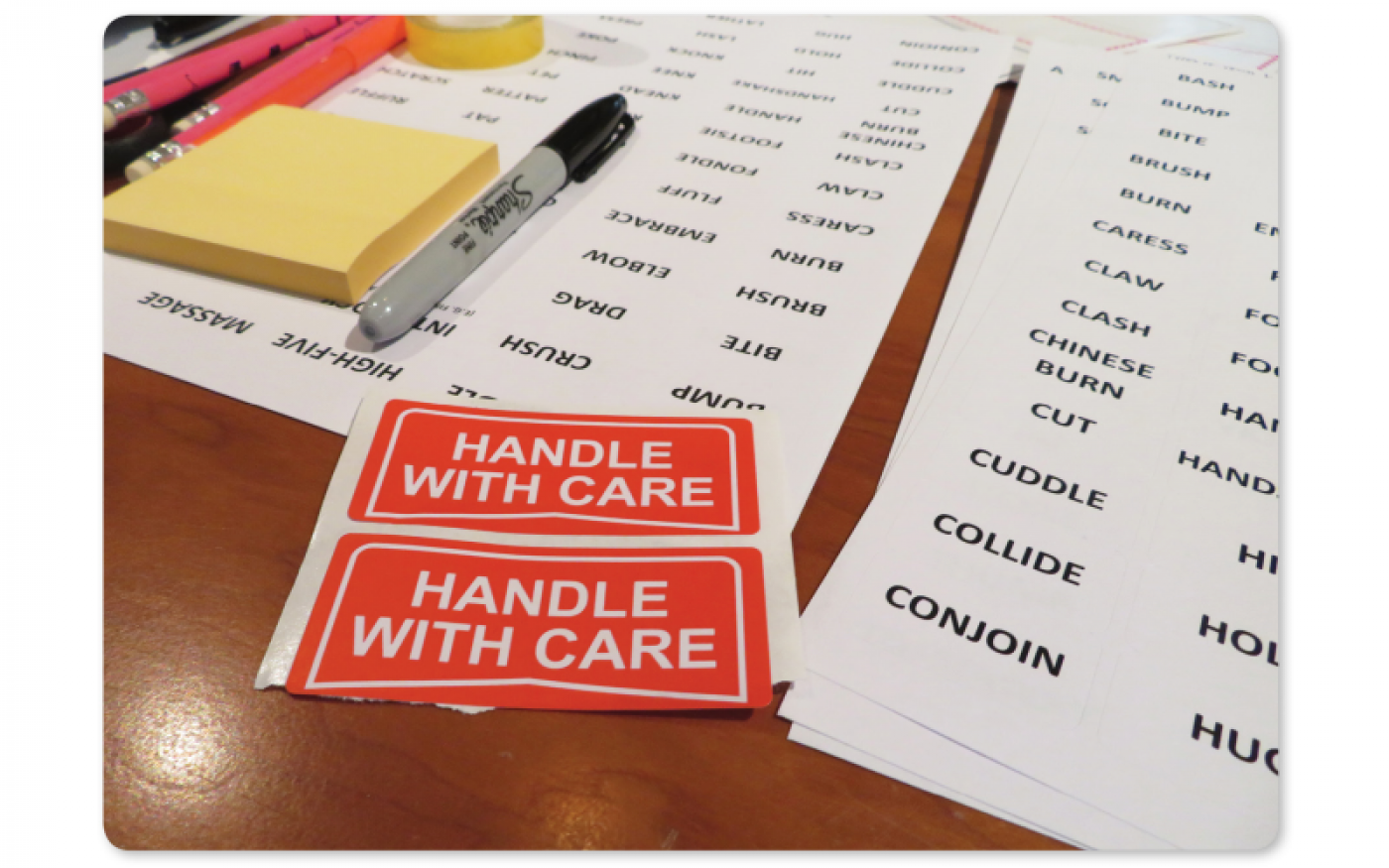

To address this problem of people being unable to talk about touch They began a project called touchy vocab.

Lili Golmohammadi 05:02

Yes, so the touchy vocab is a vocabulary that's formatted so that it can be printed as a series of sticky labels. But it's divided into two parts. On the one hand, you've got types of touch and tactile interactions. So some examples might be elbow, hog, poke. And then on the other hand, you've got words that describe tactile qualities. And some examples might be their course glassy, frothy, earthy, things like that.

Cassidy Martin 05:38

Of course, understanding our relationship to touch is always going to involve asking research participants to touch something

Lili Golmohammadi 05:45

pre pandemic. Physical workshops have included lots of different materials for participants to touch, and make associations think about their experiences.

Cassidy Martin 05:56

But how was Lily able to continue her research after touching was no longer an option,

Lili Golmohammadi 06:01

I no longer was able to be in the same room as participants using these shared resources that I made. So these tactile resources that they could touch and feel, and the touchy vocab labels that they could easily peel off and map and

Cassidy Martin 06:16

all of this, Lily, like so many of us had to switch to working remotely

Lili Golmohammadi 06:23

by being planning to use kits that you give to people with different kinds of materials, and tasks for them to do. And especially at the start of the pandemic, when we weren't really sure how the virus was transferred, it would have been really unethical to send out packs, you know, for me to go to the post office and send things to people and possibly give them the virus. So I had to put everything online, I reshaped my ideas of what these creative tasks were kind of going to be.

Cassidy Martin 06:49

Despite a lot of additional work, the remote setup did come with added benefits.

Lili Golmohammadi 06:55

Participants because they were based in their homes, they were referencing and using materials and objects from their worlds and that had real meaning for them. And in a way

Cassidy Martin 07:06

that was better created results that could not have been made in the lab.

Lili Golmohammadi 07:10

So I had one woman who really thought about touch and the comfort touch gave her through the materials that have played a role consistently across her life. She included things like a cutting of her dad's coat, and things like from her house that reminded her of her aren't all these very, very personal things that I could not have provided were were integrated into people's into people's maps.

Cassidy Martin 07:40

The work that Lily and Carrie are doing to understand touching our relationship with it is helping to guide future technologies that might help us stay in touch.

Carey Jewitt 07:50

We ran a series of design workshops where we worked with colleagues from the Royal College of Art and from the UCL Institute of making to explore people's imaginations of how digital technologies could be used in the future. around supporting touch, we had people who were experts in linguistics and language and communication, people in human computer interaction, and also people from information design and experience design. And they first kind of explored how they thought about communication and their experience of how they used phones or Skype or different kinds of video chats. And then they thought about how touch could come into that kind of communicational domain, one of the groups made something called a haptic chair. And the idea was that you'd sit in this chair and you just like can enjoy sitting there or that kind of sense of being together in a non verbal way. And it is a sense of kind of being touched by them or held by them.

Cassidy Martin 09:00

Even though I consider myself to be a pretty sensitive person to touch. I think if like in carries research in the beginning, someone asked me to tell them what touching an object was like, I would struggle with that as well. I think it's because we don't register touch sensations unless they are really good or particularly bad. In Lily's project, it makes sense that people would do better with the touchy vocab project at home. Because at home we typically feel more comfortable expressing a negative experience. And because our homes are filled with items that we have these strong positive touch sensations with either because we just like the way they feel like a fluffy scarf or a fleece blanket, or the touch of them is reminiscent of someone we care about, like in Lily's participant's case with the texture of her father's coat or for me Cold silver on my wrist of my grandmother's watch. Perhaps touching and interacting with the things that are home that bring us joy is a good way to comfort ourselves at this time before the invention of the haptic chair. So from touching to not touching, how do we stay in touch in a global pandemic? I spoke to alyssia second year natural science student who is volunteering as a Spanish teacher for Age UK, a charity that provides support and community for older people in the UK.

Alessia Qiu 10:38

Start volunteering during quarantine when the pandemic first hit, and I was searching for something to do home. And there were these newsletters from the university. And when I saw the position of Spanish teacher, I just jumped right in.

Cassidy Martin 11:01

There's a particular reason why this position appealed to Alyssa.

Alessia Qiu 11:09

I grew up in Spain, and we lived in Brussels, Belgium for about five years. So I haven't used my Spanish a lot in the past couple of years. And I just jumped to the opportunity to practice my Spanish again and put that into good use. So my parents are from China. So I'm Chinese, I have the Chinese nationality. But I was actually born in Italy. And then we spent a couple of months in China. And then we moved to Spain, then to Belgium, and then last year I went to the UK or a university.

Cassidy Martin 11:54

All that moving around growing up helped her to learn an impressive number of languages

Alessia Qiu 11:59

around six although some languages better than others.

Cassidy Martin 12:05

Did you find it difficult to pick up each language? Or do you find learning new languages got easier over time?

Alessia Qiu 12:13

It definitely got easier over time. But I think it made me very shy because I didn't talk much with my schoolmates. At first, I think it was because I didn't understand them well, and I couldn't say the things I wanted. But then when the move input more often, I would just say to myself, okay, this is going to happen again. So you have to take the chance to meet these people and at least talk to them.

Cassidy Martin 12:47

Alyssa doesn't seem to be a shy anymore. But those feelings of shyness she had growing up had given her an understanding of how to handle some of the quieter students.

Alessia Qiu 12:58

I think every lesson every session requires teachers to just put lots of energy to bring lots of energy in the room to try to come the most energetic ones and try to bring the more calm students to the discussion to

Cassidy Martin 13:18

do you feel like teaching is something that came naturally to you.

Alessia Qiu 13:22

I think it came quite naturally, because I had some previous experience with teaching, but not Spanish. But yes, since I can speak it fluently, it was nice to invite the students into the Spanish culture and Spanish language. I think it was pretty fun for me to do.

Cassidy Martin 13:44

So what does a typical lesson look like?

Alessia Qiu 13:49

lessons were carried out by two volunteers. So I was working with another volunteer called Antonio, he usually at the start, we would agree with each other in Spanish, but that was sometimes difficult. So they would just spontaneously just jump to English and it was very informal. People would just say what they did on the day or how the weather made their moods, think or be happier because there was the sun on that particular day. And then for the first half of the lesson, we would introduce some vocabulary or some grammar and then we will split into breakout rooms and then we will do some exercises that we read in advance. And then we will try to make each student have just a couple of minutes to speak and practice. And then we would go back to the main room all together and share some thoughts or just greet each other goodbye until the next lesson.

Cassidy Martin 14:58

Did you have any issues Like I know with my parents when they try to use zoom or any other type of technology thing, they tend to have trouble with it. Did the seniors seem to do pretty well with technology? Or did you have trouble at the beginning at all?

Alessia Qiu 15:21

Most of them manage. Okay, I think the organisation also provided some zoom workshops just to know the basics and how to use it for their lessons during a lockdown. But sometimes we would have problems like problems hearing someone, or someone who didn't know how to turn their microphone on or their video on. And then for example, a lady that had this problem at the end got to turn on her mic, but then she was shouting at me when we were all surprised to the sudden way.

Cassidy Martin 16:01

Despite the occasional funny little mishaps, alyssia seems to have really enjoyed her time volunteering.

Alessia Qiu 16:09

I think volunteering can always surprise you and you will always find something very refreshing and you will definitely learn something new. Well training yourself with some skills that can be useful for either your professional life or just in life. And I think the part where you get to meet new people that you wouldn't meet otherwise, it's very enriching as well.

Cassidy Martin 16:40

Alyssa has unique experience growing up eagerness to help and desire to hold on to language of her past self led her to what seems to be a fun and entertaining way to contribute to the enrichment of UK senior citizens. In a time of such isolation, having a sense of community can feel impossible. But alyssia does volunteer work proves that being part of a community is just a click away. If you would like to keep in touch with older people by volunteering to teach languages like alyssia or find out about some of the other amazing ways that UCL students are helping the community. You can find out more by visiting Students Union ucl.org forward slash volunteering. For the last part of our journey and to touch Today, I wanted to find out about how touch can be recreated after it has been lost. And so I found a researcher at UCL who is doing just fine.

Helge Wurdemann 17:50

Good morning. Um, hello, good, good. I'm Associate Professor of robotics working in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at UCL

Cassidy Martin 17:59

helped us research was recently the most highly voted breakthrough research story made at UCL, and we were so pleased to have him as our guest. He and his team in the soft haptics and robotics lab are designing and building prosthetic robots equipped with a sense of touch.

Helge Wurdemann 18:19

In my lab, we are looking into building new robotic devices. So we are understanding the sense of touch and or making the human feel what the robot can feel. So for example, if you suffer from an amputation and you lost your entire hand, you don't have any sensation anymore in your hand. So we're looking into building procedures that have sensors that can understand physical interaction with the environment and feed it back to the human on other parts of the human that are still having the sense of touch.

Cassidy Martin 18:56

prosthetic limbs that can feel and transmit touch sensations to their owners are a relatively new technology. And they are not yet widely accessible. Making prosthetics which are affordable and simple to build and have touch capabilities is a difficult task.

Helge Wurdemann 19:15

On the one side, you have aesthetic procedures, they're literally looking like the human part of your hand. They are made out of rubber or silicone material, they have the same skin colour. So they're simulating your body part and they are very reasonably low cost. And then on the other side, we have robotic or Mayo electronic diseases, they have actuators so motors in the hand driving the fingers, for instance, if you want to pick something up, they take signals from the muscle activities of the remaining stem to then open and close. Most of the mayo electronic procedures are in research states. They're also available for patients but they're very, very expensive. I would argue You bet the NHS would not pay for my electronic procedures for any MPT in the UK, they have to go through raising the money themselves and paying for this device themselves.

Cassidy Martin 20:11

To solve this problem, helpless colleagues are working on a third type of prosthetic device.

Helge Wurdemann 20:17

They are called body powered prosthetic devices, these prosthetic devices, they are not robotic, they use remaining movement of the body. So for instance, if you lost your partial hand, and you have still the functional wrist, they use this movement of the wrist to then make the hard grass. For instance,

Cassidy Martin 20:38

the challenge was to bring the sense of touch to body powered prosthetic devices, something that had never been done before. But through working with two patients at the University Hospitals in Coventry, it seems they found a way,

Helge Wurdemann 20:52

the thing at tip of our posseses is made out of rubber light membrane, and inside the fingertip is a cavity that is filled with water. When you press on to the rubber membrane, there will be pressure building up inside the system. And this pressure is then acting on another membrane which can be fitted to your forearm, and the membrane will then dilute and give you the feedback from whatever interaction you have at the thing at

Cassidy Martin 21:27

the team never would have figured this out if it were not for the feedback from these two patients. And fact, feedback from users is a vital part of every design process. And just so happens to be the favourite part.

Helge Wurdemann 21:40

One thing that I very much enjoy is when the prototype leaves the lab environment. And the reason why it is very important and very enjoyable for me is that, first of all, you see in the eyes of the people who test these things, that they either enjoyed this device or they don't enjoy it, you have the real feedback is not the scientific feedback from a journal publication or proposal review. It's actually does this device matter to the person? Does it help this person? What are they thinking, who we as an engineer designed it for. And that can be extremely motivational. But it's not creating the feedback that I hoped for can be very demotivational. But usually the people that we engage with in our tests are very encouraging. They understand that it is early research. In most cases, they actually ask Can we take it home, because they want to do further testing with it at home, how they can use it on a daily basis, etc. and also give feedback. And so this is a very modern word. It's very much in fashion, this word co creation, where you invite actually end users to help you design a device. And I think that is extremely important because we as engineers, I feel sitting sometimes in our lab and designing devices that we think could help. But if we in the first instance, ask the people that we want to help a design device for an ask them how should a device look like? What should they give you as a functionality? What do you have in your mind? What do you envision? I think that accelerates the road to developing a successful output.

Cassidy Martin 23:37

The concept of a body powered touch sensitive prosthetic is absolutely amazing to me because just creating an electronic one sounds like an impossible task. Also, just think about the world of possibilities that open up when something like that is accessible. People could actually afford it and they wouldn't have to worry about some electronic malfunction or having to be extremely cautious with this expensive prosthetic device they have and instead get real use out of it. And what a gift that is. Thank you for listening to made it UCL the podcast. To listen to previous episodes or find out more about life at UCL. Subscribe wherever you listen to this podcast. This episode was presented by me gostiny Martin and produced by Cerys Bradley. It featured music from the blue dot sessions and additional sounds from SAP splat.com Special Thanks to our guests today, Carey, Lili, Alessia and Helge for sharing their time and experience. This podcast is brought to you by UCL Minds, bringing together UCL knowledge, insight and expertise through events, digital content and activities that are open to everyone. I hope you enjoyed listening as much as I enjoyed interviewing our guests this month. Thanks again for stopping by. Take care and let's keep in touch

Close

Close