UK variant, B.1.1.7, does not increase disease severity in hospitalised patients

13 April 2021

The B.1.1.7 variant of Covid-19 – otherwise known as the UK or Kent variant – is not associated with more severe illness and death in hospitalised patients, but appears to lead to higher virus load, suggests a new study led by UCL researchers.

As part of the observational study, published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, researchers assessed 341 Covid-19 patients admitted to University College London Hospital and North Middlesex University Hospital (NMUH), between 9 November and 20 December 2020.

This was a critical time point in the pandemic, as both the original Covid-19 virus was circulating in the UK population, along with the emerging B.1.1.7 variant which had begun to spread across England, initially focused around the South East.

Researchers compared illness severity in Covid-19 patients with and without B.1.1.7 and used whole-genome sequencing data to calculate viral load.

Among 341 patients who had their Covid-19 test swabs sequenced, 58% (198/341) had B.1.1.7 and 42% (143/341) had a non-B.1.1.7 infection (two patients’ data were excluded from further analysis).

No evidence of an association between the B.1.1.7 variant and increased disease severity was detected, with 36% (72/198) of B.1.1.7 patients becoming severely ill or dying, compared with 38% (53/141) of those with a non-B.1.1.7 strain.

Patients with the variant tended to be younger, with 55% (109/198) of infections in people under 60 compared with 40% (57/141) for those who did not have B.1.1.7. Infections with B.1.1.7 occurred more frequently in ethnic minority groups, accounting for 50% (86/172) of cases that included ethnicity data, compared with 29% (35/120) for non-B.1.1.7 strains.

Those with B.1.1.7 were no more likely to experience severe disease after accounting for hospital, sex, age, ethnicity and underlying conditions. Those with B.1.1.7 were no more likely to die than patients with a different strain, with 16% (31/198) of B.1.1.7 patients dying within 28 days compared with 17% (24/141) for those with a non-B.1.1.7 infection.

More patients with B.1.1.7 were given oxygen than those with a non-B.1.1.7. strain (44%, 88/198 vs 30%, 42/141, respectively). However, the authors say this is not a clear measure of disease severity, as patients may have received nasal prong oxygen for reasons unrelated to Covid-19, or as a consequence of underlying conditions.

To gain insights into the transmissibility of B.1.1.7, the authors used whole genome sequencing data generated by PCR testing of patient swabs to predict their viral load – the amount of virus in a person’s nose and throat. The data analysed – known as PCR Ct values and genomic read depth – indicated that B.1.1.7 samples tended to contain greater quantities of virus than non-B.1.1.7 swabs.

Corresponding author, Dr Eleni Nastouli (UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health), said: “One of the real strengths of our study is that it ran at the same time that B.1.1.7 was emerging and spreading throughout London and the south of England. Analysing the variant before the peak of hospital admissions and any associated strains on the health service gave us a crucial window of time to gain vital insights into how B.1.1.7 differs in severity or death in hospitalised patients from the strain of the first wave. Our study is the first in the UK to utilise whole genome sequencing data generated in real time and embedded in an NHS clinical service and integrated granular clinical data.

“We hope that this study, and our work in the UCLH Advanced Pathogen Diagnostics Unit (UCLH APDU), provides an example of how such studies can be done for the benefit of patients throughout the NHS. As more variants continue to emerge, using this approach could help us better understand their key characteristics and any additional challenges that they may pose to public health.”

Co-author, virologist Dr Catherine Houlihan (UCL Infection & Immunity) said: “We took the opportunity to combine the numbers of patients we were seeing with the B.1.1.7 variant in our two hospitals which provided enough statistical power to examine the severity in this hospitalised population. Since we expect more variants over the next months to year, including potentially, the South African variant, we aim to continue to provide this important and timely public health research.”

Professor Mervyn Singer (UCL Medicine), said: “Whilst it is reassuring that there is no evidence of increased mortality associated with the B.1.1.7 variant, healthcare resource and patient mortality remains substantial. These data are fundamental in informing hospital and intensive care unit planning in the event of another surge. As the emergence of other variants may have implications patient management and outcome, ongoing clinical vigilance and research are imperative.”

Professor Deenan Pillay (UCL Infection & Immunity), said: “It is essential to rapidly determine the clinical implications of new viral variants as they emerge. Placed within the context of other findings, our results suggest that even though the B.1.1.7 variants may lead to higher rates of hospitalisation, our current clinical practice can manage these variants as well as earlier circulating Covid-19 viruses. Ongoing trials of new therapies aim to improve outcomes further. These important findings were made possible through the ability to capture real time clinical and laboratory data within UCLH and North Middlesex Hospital through ongoing investment by UCLH, the NIHR UCLH/UCL Biomedical Research Centre and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council-funded i-sense consortium on Early Warning Sensing Systems for Infectious Diseases.”

Professor Rachel McKendry, Professor at the UCL London Centre of Nanotechnology and Director of i-sense: "This important study highlights the power of genomics and interdisciplinary science to track the impact of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants, and builds on our strategic collaboration between the i-sense EPSRC IRC in Early Warning Sensing Systems for Infectious Diseases and the UCLH Advanced Pathogen Diagnostics Unit (APDU)."

The authors acknowledge some limitations to their study. Disease severity was captured within 14 days of a positive Covid-19 test, so patients who may have deteriorated after 14 days may have been missed in the analysis, though the authors sought to mitigate this by capturing deaths at 28 days. The analyses also did not take account of any other treatments that patients were receiving – such as steroids, antiviral medications, or convalescent plasma – or the possibility that some patients may have received ventilation for reasons other than Covid-19.

A separate observational study published at the same time in The Lancet Public Health using data logged by 37,000 UK users of a self-reporting Covid-19 symptom app found no evidence that B.1.1.7 altered symptoms or likelihood of experiencing long Covid.

Links

- Read the study paper published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases: 'Genomic characteristics and clinical effect of the emergent SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 lineage in London, UK: a whole-genome sequencing and hospital-based cohort study.'

- Profile: Dr Eleni Nastouli

- Profile: Professor Deenan Pillay

- Profile: Dr Catherine Houlihan

- Profile: Professor Mervyn Singer

- Profile: Professor Rachel McKendry

- UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health

- UCL Division of Medicine

- UCL i-sense

- UCLH Advanced Pathogen Diagnostics Unit

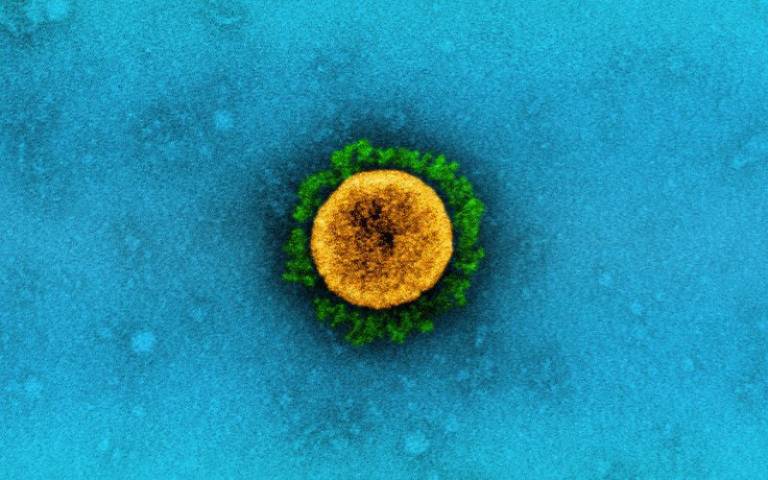

Image

- ‘Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2’ Credit: NIAID via Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Further information

- Source: UCL News

- Media Contact: Henry Killworth, Tel: +44 7881 833274

Close

Close