Governance, Capture and Corruption: Empirics & Solutions for a Changed World

30 April 2019

Blair Fu (MSc Global Governance and Ethics) on a GGI keynote lecture with Dr Daniel Kaufmann.

We don’t need to be experts in political science to have an intuitive idea of what good governance looks like. But would you be able to name one quantifiable indicator to measure the quality of governance? Where can we find reliable and comparable data on governance performance? And how can this data help us improve governance across the world? At a recent GGI keynote lecture, Dr Daniel Kaufmann (president and CEO of the Natural Resource Governance Institute) shared his insights on these issues.

Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI)

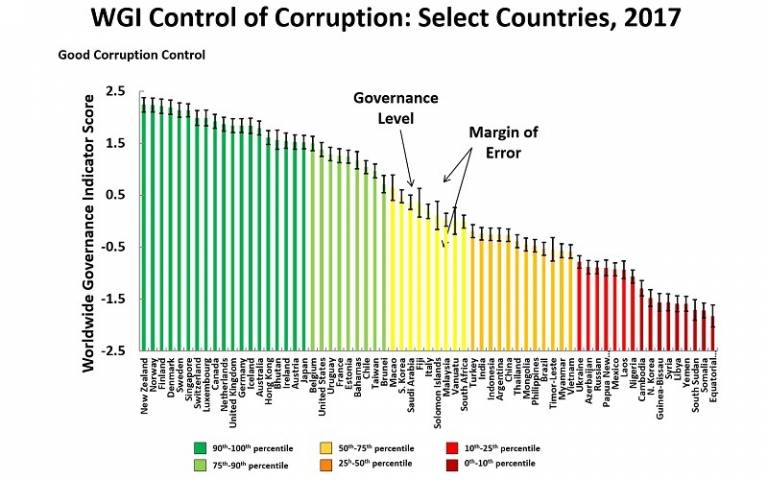

Kaufmann started his lecture by introducing the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), which he and his colleagues first developed two decades ago as part of the World Bank's Governance Matters project. Based on the definition of governance as ‘the set of traditions and institutions by which authority in a country is exercised’, the WGI assess governance along six dimensions: (1) voice and accountability, (2) political stability & absence of violence and terrorism, (3) government effectiveness, (4) regulatory quality, (5) rule of law, and (6) control of corruption.

Data on the six dimensions of governance covers well over 200 countries from 1996 until the present. It is a synthesis of hundreds of underlying indicators taken from about 30 different data sources, including a wide variety of cross-country surveys and expert polls, making it about the largest publicly-available governance database in the world. With these indicators and credible data, governance performance has indeed become quantifiable, meaning we now have a systematic way to assess, monitor and compare governance.

Source: SSRN

Non-Traditional Corruption: State Capture

One indicator which Kaufmann specifically emphasised is control of corruption. According to a report by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), about 2 trillion USD is lost annually due to corruption and bribery, exceeding 2 percent of global GDP. Although corruption has always been a hard nut to crack in governance, its form and manifestations have changed over time, with the recent rise of state capture being particularly alarming.

Traditionally, corruption is the abuse of public office for private gains. It happens during the implementation of rules, laws and policies. In contrast to such traditional forms of administrative or bureaucratic corruption, state capture (and legal corruption) is not about meddling with the implementation process, but about influencing and shaping the rules of the game. State capture might be attempted through private lobbying and influence, and it usually involves political-economic elites manipulating formal procedures and government bureaucracy so as to influence state policies and laws in their favour. Since state capture engages in the primary stage of the legislative, judiciary, electoral process, it is hard to be spotted and harder still to be proven illegal. To put it in perspective, if administrative corruption is taking a cheat sheet into an exam, state capture is manipulating what questions appear on the exam paper in the first place. In Kaufmann’s words, it is the “privatisation of public policy” – by comparison, traditional forms of corruption pale into insignificance. Thus, state capture and its drivers warrant our increased attention.

Natural Resource Curse

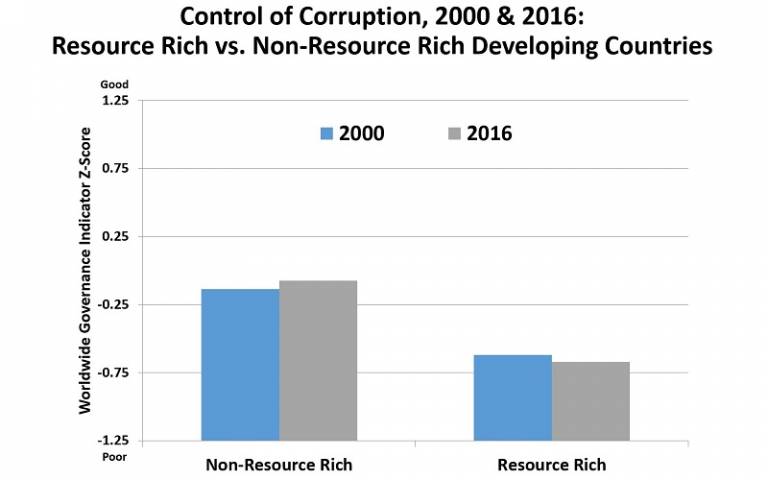

What factors encourage corruption in a given country? According to Kaufmann, the data points to the key importance of both political and economic competition. In addition, countries with rich natural resources are particularly vulnerable to both traditional and untraditional forms of corruption. Academic studies have shown that natural resource wealth tends to adversely affect a country’s governance by making authoritarian regimes more durable and increasing certain types of corruption. Ever since economic geographer Richard Aunty first came up with the term ‘resource curse’ in 1993, scholars and policy makers have found the concept useful in explaining a wide range of political maladies in resource-rich countries, especially in regions like the Middle East, Africa, Latin America and the former Soviet Union.

Most resource-intensive countries face a major ‘governance deficit’. Deep reliance on natural resources discourages politicians from investing in a state’s bureaucratic capacity. This usually shortens a government’s planning horizon and sabotages its ability to develop sound economic policies and invest in the diversification of production and exports. Major investments are therefore subverted and low-quality candidates are encouraged to compete for public office. In addition, huge rents generated by concentrated natural resources are a magnet for state capture as elites aim to exploit these rents and fight to maintain control over them. This, in turn, disincentives regular political transitions as elites are able to buy supporters and placate opponents by distributing resource rents, thus greatly impairing political accountability and stability.

This man-made resource curse persists for about one billion people living in poverty in the midst of abundance. In countries suffering from the resource curse, the poor are not benefiting from their resource riches.

Source: Worldwide Governance Indicators

“One does not fight corruption by fighting corruption”

It is critical to realise that there is no one single panacea for corruption as the nature of the problem differs from state to state. Even within the resource-rich country club, the root of the problem could lie in different parts of the governance chain. A reform might be necessary in the demand side of governance (accountability, media, transparency, open data), or in the legal and judiciary system, or in the procurement and public sector. Evidence-based diagnosis of the problem on the national, subnational and sectoral level is essential to decide where to look at and what to prioritise.

To quote Kaufmann: “One does not fight corruption by fighting corruption”. What we need on the road of fighting corruption is not more anti-corruption institutions. They are useless if we don’t know where the core problems lies. With the help of the WGI, we are now able to zoom into each sector to measure, monitor and diagnose governance maladies in a systematic manner. Admittedly, corruption will remain a hard nut to crack in the foreseeable future, but at least now we have a better toolkit to tackle it.

Close

Close