Could a Global Parliament Strengthen the Democratic Legitimacy of Global Governance?

25 October 2017

Nicole Watson (MSc Global Governance and Ethics) on the GGI keynote lecture with Dr Mathias Koenig-Archibugi.

Today's international community is facing some significant challenges, all with one thing in common: they cannot be overcome by a single state acting alone. From global warming to human trafficking, world poverty to the refugee crisis, the urgent need for collective action is becoming ever-more apparent. Yet with international institutions criticised as ineffective, distant, non-transparent and elitist, existing structures for global governance are suffering from a democratic deficit.

The idea that a world government might facilitate the global cooperation required to address transnational problems has been speculated about for at least two centuries, yet the concept remains plagued by a series of difficult and controversial questions. What form should a global parliament take? How could it be representative and democratically legitimate? These challenges were at the heart of the Global Governance Institute's recent keynote lecture, presented by Mathias Koenig-Archibugi, an associate professor of global politics at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

Rodrik's Trilemma

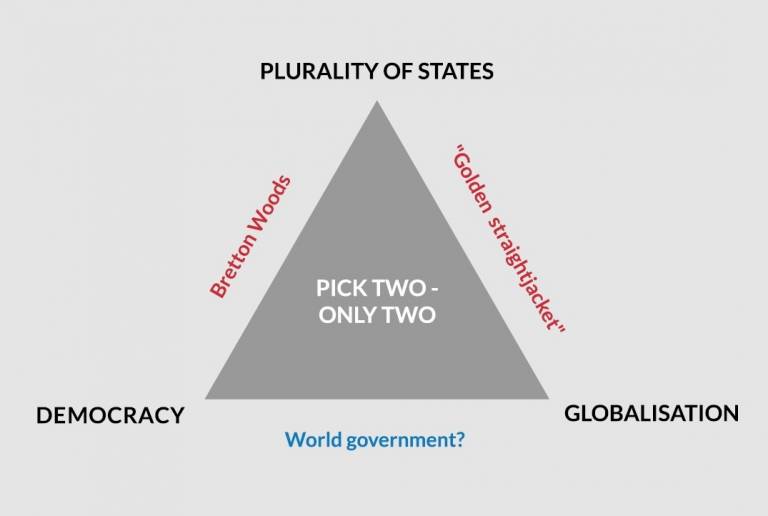

Following a whistle-stop tour through the history of the global democracy debate, Koenig-Archibugi introduced Dani Rodrik's concept of the "globalisation trilemma" - a triangular formation with "plurality of states", "democracy", and "globalisation" at its tips. According to Rodrik, the three peaks cannot co-exist: countries must pick two, and only two.

Historically, we have seen various manifestations of two peaks of the triangle. With the creation of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the fixed exchange rate system in 1944, the Bretton Woods agreement took a limited approach to globalisation and incorporated both democracy and plurality of states; the agreement facilitated the growth of international trade, whilst allowing nation states the freedom to set their own economic policies. By contrast, the embracing of what Rodrik terms "hyper-globalisation" in the 1970s boosted the world economy, but left states with little room to manoeuvre domestically. As Thomas Friedman argues, when a state dons the "golden straightjacket" of globalisation and gives up sovereignty to an international regime, "political choices get reduced to Pepsi or Coke - to slight nuances of policy […] but never any major deviation from the core golden rules." Brexiteer cries of "take back control" are just one example of backlash against the straightjacket that isn't so golden for everyone.

Forms and problems of world government

So where does this trilemma leave us? If we can only have two peaks of the triangle, which one should we give up? Can globalisation ever be compatible with democracy? Koenig-Archibugi's research seeks to answer these questions, by empirically investigating the feasibility and desirability of a world government. He focused on two possible forms a world government could take: democratic confederalism or democratic federalism. Described by Thomas Carothers as a "league of democracies", democratic confederalism would give democratically governed states an equal opportunity to represent their citizens at a global level. All members would have the right to withdraw, major decisions would be unanimously agreed on, and the confederation would have no armed forces. Democratic federalism, on the other hand, would institutionalise a more direct relationship between individual citizens and various levels of authority. A more authoritative body than the confederation, the federal decision-making body would have access to coercive power, and the final say over jurisdictional questions. Both forms have their flaws and, during his talk, Koenig-Archibugi boiled them down to three main concerns: the fear that global democracy would fail to accommodate the diversity of policy values across the world; the problem of 'persistent minorities', or groups who are systematically outvoted across all policy issues; and the argument that representatives would simply vote along national lines, rendering the system redundant.

Myth-busting with Koenig-Archibugi

To challenge these criticisms, Koenig-Archibugi turned to data analysis. Using three measures of policy preference (economic left vs right, social traditionalism vs liberalism, and whether people are willing to pay to preserve the environment), he calculated a value for the diversity and polarisation of policy preferences in each country and for the world as a whole. He also looked at overall dissatisfaction on both scales. His results were surprising: he found that, in many cases, a theoretical world democracy would have similar levels of dissatisfaction and polarisation as individual countries. This, he argued, is evidence that a world government would in fact be just as well suited to dealing with policy diversity as nation states, and no more likely to produce persistent minorities than existing democratic systems.

To tackle the question of whether a world parliament would be redundant due to delegates voting along national lines, he used the European Parliament and International Labour Conference (ILC) as case studies of existing decision-making structures above the state that are not restricted to government representatives. Koenig-Archibugi's data demonstrated that delegates at the European Parliament tended to vote more in line with their own political parties than national positions, and that there seemed to be international solidarity between workers that won out over national identity at the ILC. Although this data clearly shows that in these cases national identity was less important than class or ideology, whether this case study approach would prove robust in international forums when the delegates have less of an invested interest in the issues being discussed is a question for future research.

Final thoughts

Taking on the challenge of endorsing a world parliament is no mean feat, and Koenig-Archibugi's talk demonstrated an impressive showcase of quantitative methods to provide answers to normative questions. Nonetheless, I feel he failed to address one of the key issues with a world parliament, namely how such a system would engage with countries that have failed to democratise within their own borders. His answer was that a world parliament would either have to invite such countries in and hope that they democratise as a result, or work like a "club" requiring a country to meet certain standards before being granted a voice. Neither approach was convincing for me. Whilst Koenig-Archibugi offered some thought provoking material, I don't think Rodrik's trilemma has been resolved just yet!

Image source: "Occupy, occupy!" (CC BY-SA 2.0) by Neil Cummings (Flickr).

Close

Close