Climate Change: the Greatest Threat to Human Rights in the 21st Century

2 September 2016

Matthias Mueller (MSc Global Governance and Ethics) on a GGI keynote lecture with John Knox, UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment.

What a day - the 24th of June 2016. Brexit Day. A day on which uncertainty for Britain's future and the potential ramifications for our ability to meet global challenges was omnipresent, as a huge question mark was hung over Britain's future role in the world.

While it will take months and years to define this new role for Britain, it is clearer than ever before that more not less international cooperation is needed to address the major challenges of the 21st century. So it was all the more remarkable to hear a passionate and optimistic case for international cooperation from John Knox, UN Special Rapporteur, on this day. Debating the future of climate change and its impact on human rights powerfully illustrates how the alternative to international cooperation is a gateway to disaster.

Knox's initial task as special rapporteur was a wholesale review of the evidence and debate on the interaction of climate change and human rights. He drew two key conclusions in his study:

- There is broad agreement that climate change can and does lead to human rights violation; and

- This leads to important obligations for states (including procedural rules for transparency, consultation, minimum substantive standards, recognition of heightened duty to vulnerable groups).

Despite the omission of climate change from the major UN human rights treaties, Knox showed that the combined body of national and international standards indeed amount to significant and tangible environmental norms. This is important because, they

- Clarify what is at stake, providing rhetorical benefits to demonstrate the effect of climate change on people, their dignity and freedom;

- Provide guidance for robust climate change policy; and

- Establish institutions that provide fora for discussion and accountability.

The Paris Agreement

It is in recognition of this fact that the world came together in Paris at the end of 2015 for a historic agreement to fight climate change. And, more specifically, the Paris Agreement also represents a decisive step forward for the recognition of the human rights dimensions of climate change, containing, according to Knox, the strongest language on human rights of any global environmental treaty.

The UN's special rapporteurs are appointed to help ensure implementation of important norms and - as in Knox's case - to clarify issues when new challenges arise. In the words of Mary Robinson, climate challenge is the greatest threat to human rights in the 21st century. Climate change is increasing inequality and impacting territorial integrity and security as well as provoking the forced displacement of people and thus seriously affecting the human rights of people all over the world. Climate change related phenomena directly and indirectly threaten the full and effective enjoyment of a range of human rights by people throughout the world, including the rights to life, water and sanitation, food, health, housing, self-determination, culture and development.

Despite the scale of the challenge, Knox's position remains optimistic: Climate change is solvable and at the same time represents the key to protecting human rights in a globalised world. The major international human rights declarations do not include an environmental focus, because in 1948 and 1966 climate change was not on the agenda. As a result, climate change poses a new challenge to human rights protection.

Conceptualising the impact of climate change on human rights

The cruel paradox of climate change is that it most gravely affects those people who have done least to contribute to it, notably children, women, disabled, and indigenous people. Further, the poorest countries in the world are also disproportionately affected by climate change, despite making the smallest contribution to its causes. These countries generally have younger populations, and of course it is the younger generations across the globe that will bear the brunt of the impact of climate change.

This will translate, for example, into sea level rises resulting in significant land losses across coastal countries with huge ramifications for the people living in these areas and their human rights. Some island nations will even disappear altogether. But already today, with El Nino amplified, Eastern and Southern Africa are experiencing the worst drought in the last 100 years (thankfully the region and the world are now better at responding to the crisis than in the 1980s, so that the drought has not received as much international attention).

In Bangladesh, at any given time more than ten million people are displaced as a result of flooding. In fact, globally more than 100 million people are at risk of displacement as a result of climate change. The threat to human rights is clear and the potential ramifications are devastating. The potentially exponential growth in the number of climate refugees could pose difficult political and social challenges - a particularly salient consideration given the toxic discourse around integration and co-operation in dealing with the 'refugee crisis'. At the opening of the Paris climate summit, French President Hollande highlighted there will be millions more refugees because of climate change unless we act now.

The obligations of states met in Paris?

Notwithstanding the increasingly important role of a broad range of actors in this sphere, States remain the primary actors to push the climate agenda forward as they hold the key do both international and domestic policy-making. Climate change is a common global threat to human rights, so the first obligation on states is to work together to address it. At least to this obligation states lived up to in Paris.

Paris prescribes the important 2 degree Celsius limit for global temperature rises and sets out the ambition to keep temperature rises below 1.5 degrees. The advocacy of the Climate Vulnerable Forum under the chairmanship of the Philippines, along with many other key civil society actors, was crucial to securing the agreement on this ambition. And it was a report of UN special rapporteurs that provided the basis for the Climate Vulnerable Forum's argument of why realising the 1.5 target is crucial over the 2 degree target.

But the crucial next step is implementation, which is the true test as to whether states live up to their obligations. Paris includes a range of important implementation mechanisms, notably for climate adaptation (Article 9 of the Paris Agreement on Climate Finance) including USD100 billion of funding and the creation of new global institutions such as the Green Climate Fund, as well as the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The NDCs represent a bottom-up approach, moving the climate agenda beyond the top-down approach of Kyoto and Copenhagen, which failed. A crucial basis for the potential feasibility of the NDC approach was the 2014 pre-Paris agreement of the world's biggest emitters China and the US committing to mitigate climate change.

Nevertheless, the NDCs can represent but a humble start both theoretically and practically. Naming and shaming as a tool of governance can be effective, but invests the governance framework with little power. Practically, achieving the cumulative targets of aggregated INDCs would result in temperature rises of just under 3 degrees Celsius - or, in other words, catastrophe. Given the potential for moral hazard and backsliding on commitments, it may even be optimistic for states to adhere to INDCs if unfettered by continuous and stringent oversight. So meeting the NDC targets would still lead to massive human rights violations. That is why continuous ratcheting up of pressure to improve on these commitments is crucial, alongside a range of other mechanisms.

In order to close the compliance gap, other actors also have a crucial role to play. Faced by a unique and urgent challenge, stakeholders must employ a full range of policy tools to maintain pressure on emitting actors. For example, litigation has offered an innovating approach of holding actors to account. In Pakistan (Ashgar Leghari v. Federation of Pakistan [2015]), the US (uth Plaintiffs v US Federal Government [2016], more commonly known as the 'Our Children's Trust' case) and the Netherlands (Urgenda Foundation v The Kingdom of the Netherlands [2014]). In the landmark Urgenda Foundation case, the plaintiffs successfully brought a claim against the Dutch government, arguing that by failing to adequately regulate and curb greenhouse gas emissions, the state was guilty of negligence of its citizens. Another important tool on the other side of the coin will be safeguards to protect human rights in renewable energy and climate mitigation projects.

To tackle the question of how civil society can help turn the words of Paris into concrete action, UNICEF UK and the UCL's Global Governance Institute brought together thought leaders on climate change and human rights for a discussion on tangible next steps. The workshop highlighted how crucial it is to act now, to take the agenda to the next level and shape the norms on this important issue. For further reading, see the full report on the workshop.

A golden opportunity: Now is the time to act!

Knox concluded that the Paris agreement provides the crucial momentum to stem the crisis. The 2 degree limit is important, albeit its impact will still be dire. But it would certainly make climate change and its impact on human rights more manageable than the path we are currently on, or even than the path that the NDCs would set us on. Still, the 1.5 degree target must be our real ambition.

To realise any of these goals, the crux lies in implementation and the time to act is now. The last 2 years were the hottest in human history. We are already at 1 degree of temperature rise and without any action we are expected to hit 2.7 degrees at the end of this century. The scale of the task is immense and we are fast-approaching a make-or-break scenario. Addressing climate change is a crucial prerequisite to tackling all major global challenges of the 21st century. Without addressing climate change, we will not achieve any of the Sustainable Development Goals.

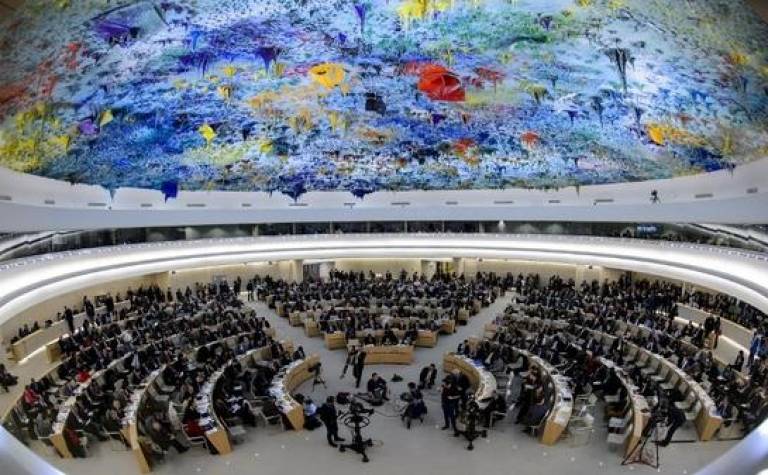

Image: Chamber of the UN Human Rights Council (Source: UNHRC)

Close

Close