Map work exercises, routes, pdfs, GCSE geography

These pages provide an introduction to some of the interesting geological features of Hampstead Heath. Both the underlying geology of the Heath and that of some of the landmarks within the Kenwood Estate (primarily Kenwood House and its surrounding statues) make excellent resources for teaching.

The material is aimed at GCSE Geography and Chemistry, or A level Geography and Geology syllabuses.

Much of the necessary information for this has been gleaned from notes by Dr Eric Robinson, formerly of the Dept of Earth Sciences at UCL, and is provided as a teacher’s resource rather than as structured exercises.

This information can be either relayed to pupils at an appropriate level, or be given directly to pupils either online or as visual aids such as overheads.

We would be delighted to see any worksheets you create based on these pages, which you might like to be included on the site.

- Kenwood House Orangery

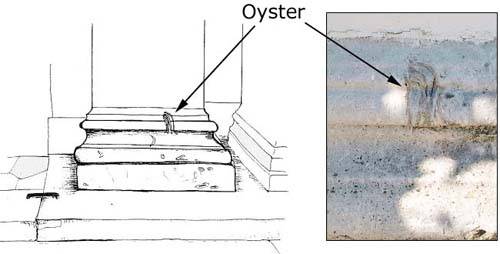

The base of the pillars of the Kenwood House Orangery are made of Portland Limestone and contain a number of raised fossils, which are visible as prominent features on the stone surface.

These fossils protrude because they are harder than the surrounding limestone, and are thus less affected by the effects of atmospheric weathering. The largest curving fossils are oyster shells.

The other shapes reflect the burrows of creatures that once lived on the sea floor. These are trace fossils.

Courtesy of Dr Eric Robinson, the Corporation of London and the Geologists’ Association

- Kenwood House Grand Entrance

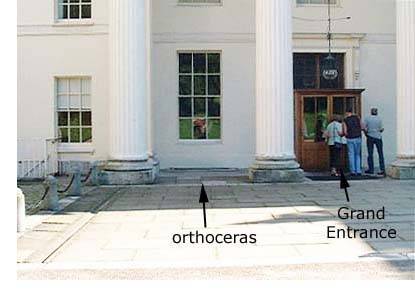

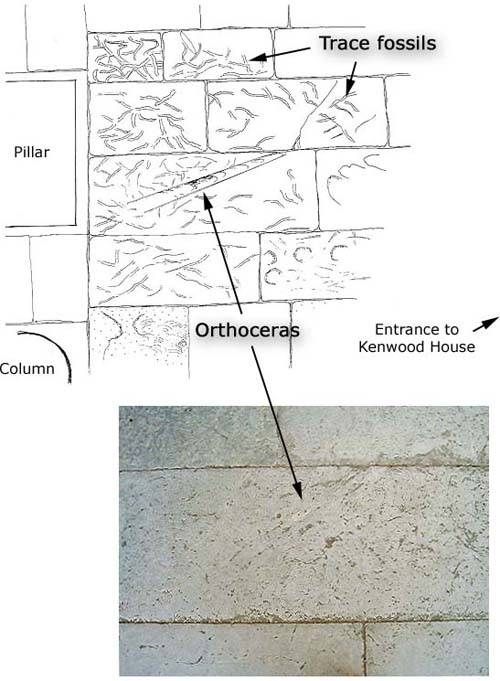

The paving stones between the columns of the main entrance to Kenwood House are geologically very interesting.

There are actually three types of stone paving in the North Entrance area, the most recent being brown York Stone flags put into the central apron and the direct approach to the entrance where foot-tread has caused wear and tear to what was the original material of the house as designed by Robert Adam in 1769.

This we can identify as the blue-grey slabs which survive between the columns of the portico, especially to the left (East) of the entrance.

Crossed by strap-like markings, these are muddy limestone slabs bearing the traces of animals burrowing in the sediment whilst it was still a soft sea-bed (bivalves and shrimps would be the animals involved), but when did this activity take place? Where does the stone come from?

Both questions are answered by the occurrence of one very special fossil. This is a long flute-shaped tube, crossed by cross partitions. This is orthoceras, related to living squid and octopus. Like cuttle fish bone, when the animal died, its shell washed up on the coastal muds, stranded to be fossilised in the mud. At times, the mud was exposed, dried out in the Sun, leaving recognisable polygonal mud-cracks.

When did this occur? This kind of Orthoceras lived about 500 million years ago in a time period known as the Ordovician. The limestone containing these fossils occurs in southern Sweden. In the 17th century, what were called Swedish Pavings were imported into England from the island of Öland in the Baltic Sea. They were used by Robert Adam elsewhere, but clearly here at Kenwood House in the 1770s.

Below: Photograph and drawing of the grey slabs known as 'Swedish Pavings' outside Kenwood House. The orthoceras fossil is pictured centre, though difficult to see here. The trace fossils (fossilised tracks formed by the movement of animals when the sediment was still soft) are very difficult to pick out.

Courtesy of Dr Eric Robinson, the Corporation of London and the Geologists Association

- Statues: Monolith Empyrean

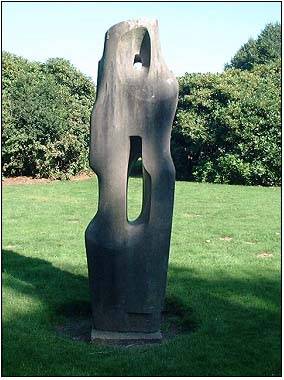

Monolith Empyrean, a sculpture by Barbara Hepworth, is situated at the far end of the lawn to the West of Kenwood House between the thick clumps of rhododendron.

The name literally means “Heavenly stone” and was sculpted by Hepworth in her characteristically abstract style in 1953.The sculpture is made of Carboniferous Limestone probably from Derbyshire (Hopton Wood Stone from Cromford in Derbyshire was often chosen by Barbara Hepworth for her outdoor work). The most interesting feature of this rock, however, is its fossil content.

Carboniferous Limestone is a hard, grey crystalline and well-jointed rock that contains numerous fossils including corals, crinoids and brachiopods. These indicate that the rock formed in a warm, clear sea suggesting that Britain once lay in warmer latitudes. Carboniferous limestone is predominant in the Peak District and Yorkshire Dales where it forms a distinctive landscape known as karst.

Although no corals are visible in the sculpture, numerous crinoids and brachiopods can be seen.

Crinoids

Looking closely at the matt grey surface of the stone reveals numerous raised shapes. Most are disc-shaped with a hole in their centre, not dissimilar to polo mints!

Each of these discs would originally have been threaded through by muscle tissues to form the flexible stem of a crinoid, the distant relative of sea-urchins and starfish.

Crinoids flourished in sea-bed forests on the floor of the Carboniferous seas, their lime skeletons accumulating to form limestone.Their shapes identify geological time as clearly as dated coins at an archaeological dig.

Brachiopods

These are bivalve shells that appear as white outlines on the stone surface. They are often crescent shaped, showing a cross-section through a curved shell.

Courtesy of Dr Eric Robinson, the Corporation of London and the Geologists’ Association

- Statues: Flamme

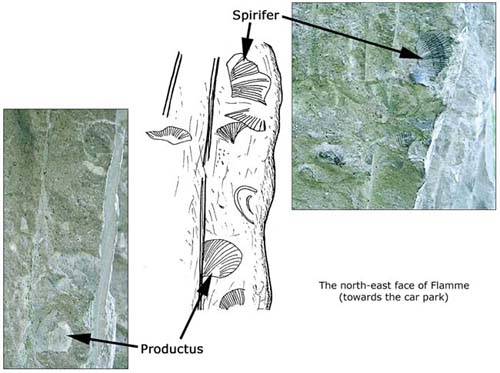

- This statue, by Eugene Dordeigne, situated near Kenwood House, is often rather overlooked if not disregarded. However, in terms of geology it is a very interesting piece.

The sculpture is carved from limestone, almost certainly Carboniferous in age (350 million years before present).

The limestone is possibly from Derbyshire but could also have come from the Meuse Valley in Belgium. This can be determined on the basis of the fossils which the stone contains.

The markings that can be seen upon the surfaces (see below) are lime shells of animals which lived upon the sea-bed about 350 million years ago.

Most are bivalved shells of the kind called brachiopods. One is triangular and ribbed. It is called spirifer. Another is more rounded in outline but also ribbed. This is productus. The shining “mirrors” are discs of the mineral calcite (calcium carbonate). These were originally stem segments of sea-lilies or crinoids.

Courtesy of Dr Eric Robinson, the Corporation of London and the Geologists’ Association

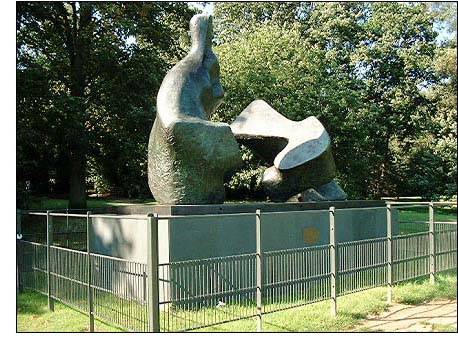

- Statues: Reclining Figure 5

Although the rocks which underlie Hampstead Heath, like those across Southern England, are sedimentary, items such as statues allow us to observe more unusual, and out of place rock types.

A good example is the bronze statue by Henry Moore, namely Reclining Figure No. 5. However, it is not the statue itself that is of interest, but the box-like plinth on which it sits.

This plinth comprises a number of separate panels, some of which clearly match up in colour and texture. Look at the ones which look more blotchy than the others. Notice the pale buff colour patches which stand out against the blue-green body colour of the stone. There are also pale buff streaks which run across the slabs obliquely from top right hand corner to bottom left.

This rock is a kind of slate, but, there is more to it than that. The pale buff patches have fuzzy edges: they merge and disappear into the background stone. This effect results from an ancient volcanic eruption. As the volcano erupted, it would have blasted molten lava high into the sky. As this lava fell, still red-hot, it fused with the vast quantities of volcanic ash produced in the eruption, and together, the ash and lava then rained down upon the surrounding countryside.

Just this kind of ash was produced in the famous eruptions of Mount St Helen’s in the Rocky Mountains, USA (1980) , and Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines (1991).

The rock seen here, however, is nowhere near so recent, being deposited about 450 million years ago (Late Ordovician). It is Lake District Slate, and would have been quarried from the heart of the Lake District.

Courtesy of Dr Eric Robinson, the Corporation of London and the Geologists’ Association

- Springs on the Heath

Hampstead and Highgate have always been well known for their springs as a source of water for different purposes.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the springs were a basis for a busy laundry service for the growing population of London. Some waters were ‘hard’ (a high lime-content), while others were ‘soft’. These properties were used for starching linen.

Other springs containing iron salts (known as chalybeate springs) were thought to have medicinal properties and became a basis for health spas.

The waters for springs accumulates in the porous sands of the Bagshot Beds, which form the upper parts of the Heath. They absorb water like a sponge and allow rainfall to pass downward until it reaches underlying clay beds, at which point, groundwater flows laterally to emerge on the hill slopes as visible springs.

Springs flowing from the sand-clay junction then form the head waters of the streams of the Heath, all of which join up to become the Fleet River.

All springs reflect the types of rock that lie beneath the surface of the Heath and so help us to create the geological map of the Heath.

In winter and early spring, water can flow freely from the sands, and springs will be quite obvious on the hill slopes of the Heath. Later, it may not be quite so easy when the drier, warmer weather comes along. In some areas, however, there will always be a good chance of finding the spring-line.

Where are the springs?

Plant life will give the best clues. Look for areas of yellow irises and where the yellow buttercups are thickest. These colourful flowers identify ground that is permanently wet.

South Meadow, running down to the Ladies Bathing Pool, is one good place to look.

Cross section X-Y through the above map:

- Bricks on the Heath

Between 1866 and the end of the century, there was an extensive brickfield on the West side of the Heath, stretching from The Viaduct down the valley of the Hampstead Ponds. It was an enterprise generated by Sir Thomas Maryon Wilson to allow John Culverhouse, a local builder, to make the bricks needed for the extended terraces of the village.

Geologically, the ground of the brickfield was underlain by London Clay overlain by silts and clays of the Claygate Beds. Together, they make an excellent blend of materials for brick-making. When fresh and unweathered, London Clay is rich in iron pyrites (sulfide) which changes to sulfate on exposure to air. Sulfate takes the form of crystals of gypsum (calcium sulfate) — liable to cause bricks to burst when they are fired in a kiln.

On the Heath, the clay was dug by hand, and cut from terraces notching the hill slopes below the Viaduct. It was then left exposed to the rain so as to flush out the gypsum. Finally, it could be blended with the fine silts of the Claygate Beds together with the brick earth (wind-blown silt from the top surface of the Heath).

Many of the bricks were fired in very simple kilns. If the wind was in the East, the reek of sulfur smoke must have hung heavily over Hampstead. The product was a yellowish stock brick. The outer bricks of the kiln often fused together to form distorted blocks with glazed surfaces which can be seen in garden walls throughout Hampstead. More information on brick making is provided under Clays and bricks.

Courtesy of Dr Eric Robinson, the Corporation of London and the Geologists’ Association

Where were the brickfields?

Clay was cut over both sides of the valley (really the headwaters of the River Fleet) at the height of workings. It would be difficult to identify the area in the present land-scape. The benches and terraces have been levelled; the football field occupies the uppermost level. Elsewhere, the thick and tangled vegetation of the valley above the Mixed Bathing Pond, and again towards the Vale of Health, may indicate the deep disturbance of the ground.

Like the sand-pits of Sandy Heath and The Spaniards Road, the disappearance of the Brickfield is evidence of the speed with which nature colonises open space and broken ground. Ecologically, this is an area of the Heath given over to invasive species.

- Pebbles on the Heath

The paths of Hampstead Heath are covered with rounded and polished pebbles. Sometimes they are black, other times they are amber or brown. Often they are broken across with a clean fracture, and can have quite sharp edges.

They are pebbles of flint, the material that was used to make cutting tools by early man. Worked flints have been found at sites on the Heath, but the ones seen lying on the paths have been fractured by natural causes such as accidental collisions.

All flints are derived from chalk. Their shape is not perfectly round, but more elongate like the shape of an egg. This is the shape of pebbles rolled along the bed of river. These were therefore riverbed pebbles.

Pebbles of this same type are to be found running through sand deposits resting on top of the chalk in Hampshire and Berkshire, especially the heathlands around Bagshot. It seems that a great river (The Great Bagshot River) laid down sands from Salisbury Plain, through Bagshot, reaching North London before flowing into an early North Sea.

Courtesy of Dr Eric Robinson, the Corporation of London and the Geologists’ Association

Where do the pebbles occur?

Lines of pebbles can be seen running through the yellow sand on the banks of the ponds on Sandy Heath or in the steep cuttings to the road down to Golders Green.

There is an old sand quarry in North Wood just off the carriage-drive to Kenwood House. In the old face of this quarry there are seams of the rounded pebbles, just the same as the ones found in the paths.How do they come to be on the paths?

The answer is erosion and gravity.

Erosion: Rain and frost loosen the sands in the slopes, the sand washes away, and the pebbles fall.- Gravity: The slopes of the Upper Heath cause the pebbles to roll down and accumulate on the flatter areas like a scree.

When did the river flow?

The Bagshot River was eroding the chalk of Wiltshire and possibly Devon some 50 million years ago. The flints were broken down and rounded in transport, to end up in the Bagshot Sands of the London Basin.

- Sand on the Heath

Sand is a word naturally associated with the word heath, and it is sand or sandy soil that gives rise to the distinctive vegetation that we see on heathland. The presence of gorse or broom is a strong hint that locally, soils are light, well-drained and probably quite loose in texture. We often use these characteristic features of the plant cover to deduce that the soil and the underlying geology are sand or sandstone.

How can this be proved on the Heath?

Looking at the slopes of Mount Tyndal or the hummocky ridges of Sandy Heath across The Spaniards Road, two lines of evidence are a great help:

First there are the rabbit holes. Thrown out from their burrows is light yellow soil which is pure sand.

Second are the trail bikers skid-marks which show the same yellow sand in their tracks.

Then there is the historic record of photography. In the 19th century, sand was dug from pits on Sandy Heath to dry up the rutted and muddy streets of London. In two World Wars, sand-bags were filled from the same sources. Years ago, the oak and birch woods beyond The Spaniards Road was bare ground pock-marked by sandpits.

Nature is a great healer. Post cards survive to record those former uses. More elegantly, there are paintings by Constable and sketches by almost all the painters who chose to live in Hampstead and Highgate, recording the sandpits in differing states of working or natural reclamation.

Where can the sand be seen?

The sand of Sandy Heath, and the higher parts of the Heath (above 90m), is from the formation known as Bagshot Sands. These sands cap the thicker clays which form the foundation to the Heath and are directly responsible for the heath vegetation of gorse, heather, birch trees and pine trees. At the junction between sands and clays, we find the main springs coming to the surface another point at which to detect sands.

When the Great Storm of 1987 flattened trees which were still in full leaf, large beeches and oaks rooted in the sands were toppled so that their root-spreads were exposed to view. Within those roots and in the pits opened up at their base, we were able to see the Bagshot Sands.

Today, more than 15 years on, yellow sand can still be seen in situ. Three of these pits are shown on the map below:

Below, the Ken Wood Pit. A fallen tree reveals the underlying Bagshot Sands

The Bagshot Sands are, however, best exposed in the Old Quarry of North Wood, next to Kenwood House.

The Old Quarry in the North Wood

This was a source of sand for the Kenwood Estate when it was a residence supported by gardens and set in parkland with carriage drives. Sand was used to lighten soils, but in greater quantities, to maintain path and drive surfaces rutted by rain and slope movement under gravity. It was also used in all building work for cement-mortar, wall renderings and concrete. Active use of the quarry ended last century.

Now, it is quite difficult to recognise the slope embayment as an old quarry, due to the growth of trees and ground spreads of bramble and bracken. In the interests of science, however, plans are being made to cut a sector of the slope in order to expose what could be the only visible outcrop of Bagshot Sands in North London.

The Great Bagshot River

The Old Quarry in North Wood has been designated a Regionally Important Geological Site (R.I.G.S) by English Nature, the agency for Nature Conservation Work in England. The importance referred to here is the set of observations that can be made in the Quarry, and the geological conclusions derived from them:

The sands are fine-grained and free-running. Not the coarse gritty sand of a sea-beach, but rather the fine grains of a large-scale river silty rather than gritty. Test them between your fingers. Look for silvery flakes of the mineral mica. These float freely and sink slowly to the bottom when the current is slack. This fine sand accounts for several metres of the total face of the Quarry. Some levels are peppered with seams of pebbles. These are the rounded pebbles we find washed out from the sands on the slopes of the Heath. All are flint pebbles, weathered out from the chalk of the Wessex Downs, rounded as a result of being swept along by moving water. Rarely, there are other pebbles which must have come from somewhere like Dartmoor.

Below: This is the path that the Great Bagshot River probably followed about 50 million years ago. The river would have been a similar length to the Niger, Indus, or Ganges Rivers today.

Putting these observations together builds up a picture of The Great Bagshot River flowing from SW England, across the Salisbury Plain, to deposit thick river sands in the London Basin. The lines of pebbles record periods of flood when the river had more potential to carry larger particles.

- Sphagnum on the Heath

- Sphagnum is a spongy, usually waterlogged, green moss. It’s success depends on copious supplies of water. Hampstead Heath has its very own sphagnum moss bog. This may seem unusual, since the word “heath” suggests well drained, sandy soil, supporting plants such as gorse and heather, not sphagnum. So why is it present? Due to the geology. The upper parts of the Heath are indeed drier because the underlying soil and “rock” are Bagshot Sands. However, within those sands, there are thin bands of clay. These clay bands locally prevent groundwaters from sinking further, and as a result, waters collect above the clay layers, where they can provide mosses such as sphagnum with all the moisture required for successful growth. This is called a “perched water table”.

Where is the sphagnum?

As sphagnum would not be expected to occur on dry heathland, when it does occur, it is sufficiently unusual for it to be registered with English Nature as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (S.S.S.I). On this count, it isn’t somewhere that should be too “public” or visited, in case it should be damaged.

It is no secret, however, that the site is in the upper part of West Meadow, clearly visible from the scenic path winding its way to Kenwood House from the Hampstead Gate.

Disclaimer

The information contained on this website is believed to be correct at the time of posting. However, please bear in mind that alterations may be made to signposts, paths etc. on the Heath.

If you find that anything has changed in such a way as to affect the exercises provided here, please let us know.

Access

Access to the exterior of Kenwood House is freely available to the general public. Please bear in mind, however, that the house is sometimes used for functions, and care must be taken to keep noise and disturbance to a minimum.

Please take great care to ensure that no damage is caused to the fabric of Kenwood House or any of its surrounding statues. It should not be necessary to handle any of the rocks when, for example, examining the fossils – LOOK BUT DO NOT TOUCH!

Hazards

We have constructed these exercises so that possible hazards are minimized. However, please note that the Heath contains several large areas of open water, and at least one high level viaduct. Students should, therefore, be closely supervised; particular care should be taken to allow sufficient time to finish the exercises in daylight hours as the Heath may not be safe after dusk.

Close

Close