Auditory and nonverbal cognition

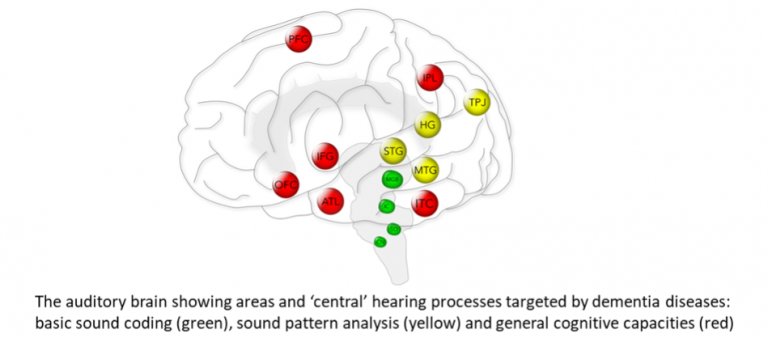

Hearing is crucial to everyday communication but we hear with our brains – and the processing of sounds under natural listening conditions presents the brain with an extraordinary computational challenge that may expose the effects of neurodegenerative disease. Indeed, hearing impairment has emerged as a major factor in cognitive decline – but we do not understand the basis for this association and we currently lack tests that assess the listening brain – ‘auditory cognition’. A major focus of our work is the development and systematisation of such tests and their evaluation in defining the distinctive auditory phenotypes of major dementias and in developing novel auditory ‘stress tests’ that could act as proximity markers of dementia onset. An allied programme of work in the lab explores analogies and links between auditory and other nonverbal sensory modalities – vision, olfaction and taste – in major dementia syndromes. A closely integrated, overarching aim is to link auditory and other nonverbal cognitive deficits to underlying profiles of brain damage and dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders.

Communication deficits and their treatment

Many dementias affect production and understanding of speech and language, most dramatically in the ‘language-led dementias’ or primary progressive aphasias. However, speech processing is dauntingly complex; and much daily life communication is nonverbal and at least as vulnerable to the effects of dementia. We seek to deconstruct speech and nonverbal communication signals into their perceptual and cognitive building blocks and to determine how these map onto the neural processes targeted in neurodegenerative disease. A ubiquitous vocal signal such as laughter has deep neurobiological roots that link us to other primate species and access core features of neocortical operation. Equally, it is a rich and nuanced model for understanding how the brain processes social and emotional signals and how these processes are affected in different dementias at a physiological level – indeed, ‘laughter phenotypes’ of dementia can capture such complex phenomena as impaired understanding of social authenticity and inappropriate emotional reactions to other people. We are also applying measures to characterise features of everyday communication that could identify particular forms of dementia. Ultimately, we aim to use this information to guide the development of new diagnostic tools and interventions to improve communication functions in people living with dementia.

Music and predictive cognition

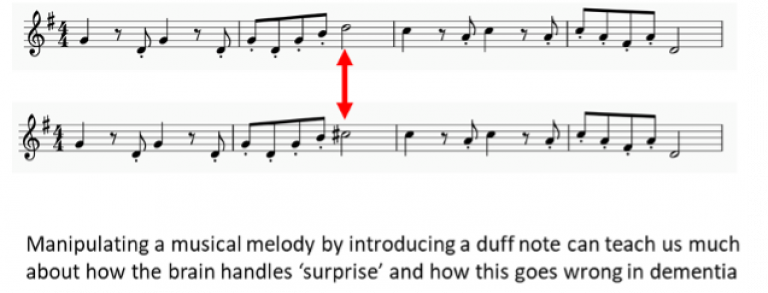

The uniquely human phenomenon of music has much to teach us about our brains and the impact of neurodegenerative disease. The major syndromes of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease produce distinctive signatures of impaired perceptual, cognitive and emotional responses to music – and sometimes strikingly preserved musical capacities even as other aspects of cognition are eroded. We are particularly interested in the propensity of music to build expectations – and the associated cognitive and emotional processes around musical ‘surprise’ – as these tap a fundamental principle of brain operation, ‘predictive coding’ of the world at large. Many of the behavioural effects of dementia – such as impaired ability to plan and to deal with unexpected events and the behaviour of other people – are likely to reflect impaired predictive cognition, suggesting that music may be a relevant probe of the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms.

Retained cerebral plasticity

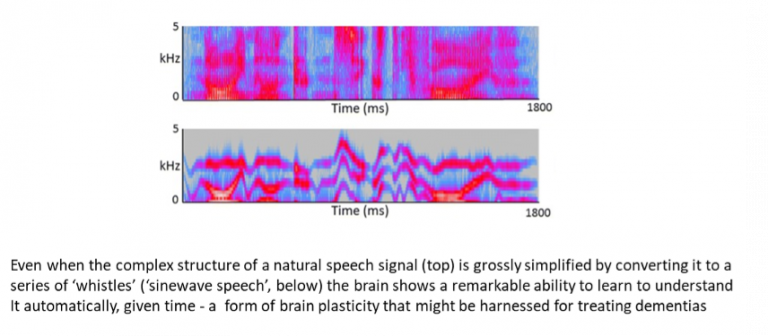

A critical but under-explored dimension of dementia is the brain’s retained capacity for neural adaptation and compensation. This capacity will be a key target for disease modifying therapies to restore brain function, so it is essential that we develop tools and markers for assessing it. One promising candidate tool is adaptation or ‘perceptual learning’ in response to degraded (noisy) speech – this occurs automatically in healthy listeners and we have shown that, remarkably, dementias such as Alzheimer’s disease and progressive aphasia have retained perceptual learning that may be modulated by pharmacotherapies such as donepezil. This opens up a broader perspective on other dynamic brain phenomena (such as illusions) and the future development of specific cognitive rehabilitation strategies.

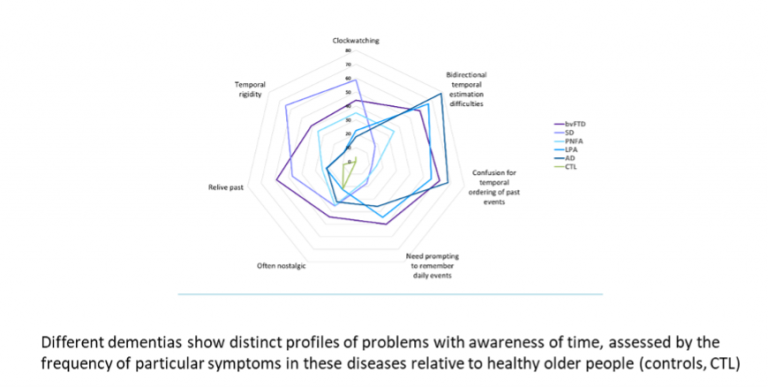

Temporal perception and awareness

Our awareness of time is fundamental to our sense of self and impacted in a variety of ways by neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and the frontotemporal dementias, including disordered mental timelines, impaired judgment about time and clockwatching. Temporal perception depends on fundamental ‘clock’ operations instantiated by neural circuits that are targeted by these diseases. However, very little is known about the brain mechanisms of disordered temporal awareness in dementia. Our work addresses the phenotypes of abnormal temporal processing over different timescales – ranging from seconds to a lifetime – and how cognitive and emotional contexts affect temporal awareness in different dementias.

Embodied cognition and physiology

A core cross-cutting theme of our work is the pathophysiology of bodily reactions to cognitive and emotional signals and their role in disordered interoception and self boundaries in dementias. We integrate autonomic – chiefly pupillary and cardiac – recordings, tactile and muscle EMG responses with functional neuroimaging to delineate profiles of homeostatic processing in the frontotemporal dementias and Alzheimer’s disease and to determine how these relate to impaired processing of emotional signals in these diseases. This work is building up a complex picture of impaired awareness of bodily signals, altered physiological reactivity to others and abnormal self/non-self differentiation at different levels of neural organisation across the dementia spectrum. Ultimately, work of this kind is likely to lead to improved understanding of phenomena such as loss of empathy and psychosis that represent a significant burden of care and distress in dementia.

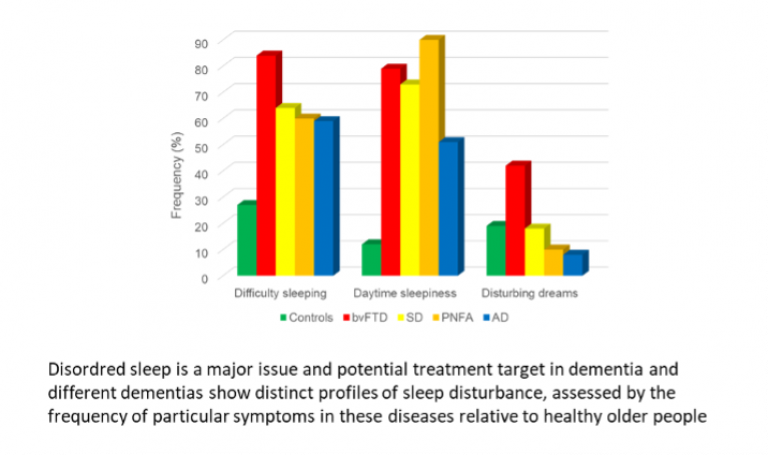

Sleep phenotypes and pathophysiology

Sleep disturbance is at once an immensely challenging management issue, a crucial window on the pathophysiology and a potential driver of the pathological process in neurodegenerative diseases. Our work seeks to link disordered sleep and circadian cycles to cognitive and behavioural symptoms and underlying electrophysiological and neurochemical changes in people with frontotemporal dementias and Alzheimer’s disease. Ultimately, we aim to identify new ‘hypnic’ biomarkers of these diseases that signal the pathophysiology of pathogenic protein spread in vulnerable neural circadian circuitry and present targets for disease modification.

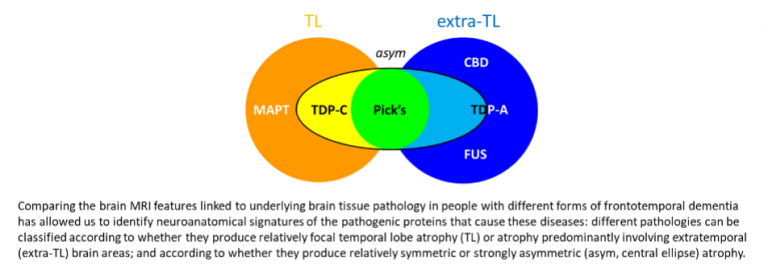

Defining and modelling molecular nexopathies

We have proposed that major neurodegenerative diseases are ‘molecular nexopathies’ – coherent conjunctions of pathogenic protein and neural circuit characteristics producing specific clinico-anatomical phenotypes – based on the detailed phenotypic analysis of large longitudinal cohorts of patients with frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, with genetic and histopathological correlation. This work is identifying empirical ‘rules’ of molecular phenotypic correlation across this disease spectrum, and we seek to derive these rules from first principles by simulating the spread of pathogenic proteins with specified properties in a synthetic neural network using computational modelling. Ultimately our aim is to identify new physiological markers of neurodegenerative diseases that predict culprit proteins and assay their phenotypic activity.

Close

Close