CBER History

Opened in 2013, the UCL Centre for Biodiversity and Environment Research is an interdisciplinary centre that undertakes research between biodiversity and environmental change. It represents the latest incarnation of UCL’s illustrious history in ecology and the environment.

First University Degree in Zoology in Britain

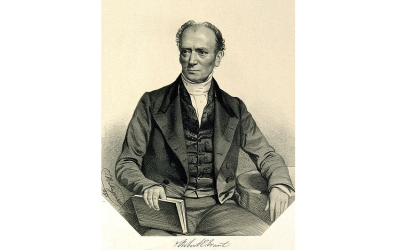

The emerging disciplines of biological field studies and of ecology have been embedded in UCL from the early days of both the College and the sciences themselves. Before moving south from Edinburgh to become the first UCL Professor of Zoology, Robert Grant introduced Charles Darwin to systematic biological surveying, demonstrating to him the animals on the shores of the Firth of Forth and so providing essential training for Darwin when he left a few years later for his voyage on the Beagle.

At the same time, UCL’s first Professor of Botany, John Lindley, was chairing an enquiry which effectively rescued the Royal Botanic Garden at Kew from the Chancellor of Exchequer’s intention to dispose of it to save money. He was succeeded at UCL by one of his Kew staff, Daniel Oliver and then in 1888 by Daniel’s son, Francis.

Francis Oliver and Blakeney Point

Francis Oliver was a very significant mover and shaker in transforming traditional “nature study” to scientific natural history and establishing fieldwork as an essential complement to laboratory and museum studies. Oliver’s background was in palaeobotany, but the fossils he studied led him on to an interest in their distribution and thence to plant geography. In 1903, together with a young colleague, Arthur Tansley, Oliver took a small group of students to study marsh and water associations around the Norfolk Broads and the nearby coast.

Over the next few years, he extended these expeditions, taking larger groups to the French coast, near St Malo, and then to Blakeney Point in Suffolk. The results from these studies in maritime vegetation were instrumental in transforming botany from a static description of the status quo to a concentration with dynamic process of colonization and extinction.

Meanwhile in 1904 Tansley, in an unrelated but synergistic initiative, was pivotal in establishing a “Committee for the Study and Survey of British Vegetation” to explore the factors determining and differentiating plant communities.

Birth of the British Ecological Society

In 1913 at a meeting in UCL, this Committee opened its membership and rationale to become the British Ecological Society, the first Ecological Society in the world; the Committee members formed the first Council of the Society with Tansley as its first President. Oliver succeeded him as President two years later. Tansley moved to Cambridge in 1907 (and later to Oxford as Professor of Botany), remaining a key influence for nature conservation in Britain throughout his life – playing a large part in persuading the Government to set up the Nature Conservancy (now devolved into Natural England, Scottish Natural Heritage and Nature Resources Wales) with Tansley as its first Chairman.

Despite his distinguished career, he looked back on his time at UCL as a particularly happy and profitable period. Whilst at UCL, Tansley founded the journal, New Phytologist, which remains one of the most important botanical journals.

In 1912, Charles Rothschild, a member of the Rothschild banking family, set up the Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves (SPNR), to identify and preserve “areas of land which retain primitive [i.e. ancient and semi-natural] conditions and contain rare and local species liable to extinction owing to building, drainage, disafforestation, or in consequence of the cupidity of collectors”. Helped by a substantial donation from Rothschild, Oliver bought Blakeney Point and established there the GEE Field Station, still regularly visited by students.

First voices seeking protection of Nature Reserves

The following year (1913), Oliver spoke at the Winter Meeting of the British Ecological Society, noting the establishment of the SPNR and calling upon ecologists to consider the function and management of nature reserves, pointing out that the few nature reserves in England formally recognized at the time existed more by accident than any deliberate policy, perhaps because “the country districts of England are not obviously and seriously threatened, hence the Nature Reserve movement lacks any background for a strong public appeal.”

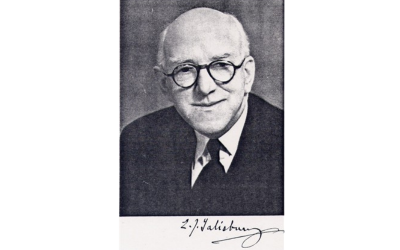

His pessimism seems to have been justified; for a long time there was little effort to increase protection; Oliver became increasingly concerned about the need for action. Most debate in the interwar decades centred on the establishment of large national parks which were supposed to include nature conservation in their remit, despite doubts repeatedly voiced about the likely inadequacy of such a procedure. Edward Salisbury (who succeeded Oliver as Professor, and then went on to become Director of Kew) declared that “the survival of a large proportion of plants and animals depended upon ‘active control’ and ‘informed imagination’, and ‘a properly constituted body was needed for that purpose’.”

First Statutory Nature Conservancy

It took over 30 years from Oliver’s plea for such a ‘properly constituted body’ to be established. Not until 1949 was a statutory Nature Conservancy set up, “to provide expert advice on nature conservation, designate and manage a series of national nature reserves, and to undertake such research as was relevant to those functions, over and above the more fundamental, long-term research expected of a research council”. Oliver, Salisbury, W.H. Pearsall (Salisbury’s successor as Botany Professor) and above all, Tansley were key agents in its establishment; Tansley himself was its first Chairman.

In its early years, many of the Nature Conservancy staff were forestry experts, returning from posts in the declining Empire. As this source of expertise began to decline, the then Director of the Nature Conservancy, Max Nicholson, asked help from the Provost and Pearsall at UCL. The result was the establishment at UCL of an MSc course in Conservation Biology, taught jointly between the Biology Departments and Geography. Many leading conservationists in both Britain and elsewhere are graduates from that course.

UCL Grand Challenges

In 2009, UCL launched Grand Challenges. UCL Grand Challenges convenes and cultivates cross-disciplinary collaborations that explore interconnected solutions in six areas related to matters of pressing societal concern. At the heart of such collaborations is the realisation that social justice and sustainability cannot be achieved without the conservation of the natural world.

Three of the six Grand Challenges areas were Global Health, Sustainable Cities and Human Wellbeing. Ecology and Biodiversity are critical elements of all three. This plus an increase in interest from both prospective students and researchers in these areas led UCL Biosciences to develop the Centre of Biodiversity and Environment Research in 2013.

UCL created interdisciplinary research domains to address the Grand Challenges. CBER has been the ecological heart of UCL’s Environment and Food, Metabolism and Society research domains.

Measuring the Success of Conservation Efforts

At that time conservation was focused on looking at specific species, particularly rare ones, and monitoring their population levels. UCL and CBER were critical in re-framing conservation to focus on nature as a dynamic concept and to look at understanding and quantifying the changes taking place within it.

UCL’s radical history made it the perfect place to question and re-examine the commonly held beliefs in this critical area. UCL and CBER championed a move from opinions to facts in biodiversity and to shifting the focus to interdependencies with human economies and well-being.

What happens when we experience biodiversity loss and climate change together? Whilst there is broad awareness of the issues we face when it comes to climate change we don’t know the effect that change will have on ecosystems like coral reefs or rainforests – and how their changes will influence each other. How do all of these elements interact and how are they interdependent?

Almost every measure of biodiversity and planetary health has seen huge reduction over the last 50 years. How much more extinction now is there than there was in the past? Where and when will be the tipping points in ecosystem health? Where and how should conservation efforts be targeted to achieve the maximum success and benefit to ecological and social justice?

UCL and CBER's efforts in asking these questions and addressing these challenges helped to change how biodiversity loss is measured, shaping novel indices like the Living Planet Index. Our efforts were also integral to going beyond the consideration of individual species to describing how rapidly populations of many species are in decline across different ecosystems. By focusing on changes in population size over time such measurements can better predict tipping points in nature, and when and where dangerous levels of environmental change are being exceeded.

Today CBER continues to conduct ground-breaking research in biodiversity and the environment that is crucial in bringing the ecological emergency to the attention of the media, and that catalyses and directs the actions of policymakers.

Close

Close