From 3D scans of The Bartlett's buildings to Arctic sea ice and ancient ruins, Bartlett alumni-founded ScanLAB is digitising the world one building, landscape and object at a time.

What should you do if a sea ice scientist from Cambridge University calls and asks if you want to join him on an expedition to Svalbard to scan Arctic sea ice? Drop everything and go, of course.

The scientist in this case was Till Wagner and on the other end of the line were Will Trossell and Matt Shaw, both alumni of the MArch programme at The Bartlett School of Architecture and, at the time, juggling jobs in the industry with trying to get their business, ScanLAB, off the ground. Here was Wagner offering them the chance to capture the 3D form of ice floes in the Arctic; to help him understand their shape and elasticity. “We just said ‘yes – let’s go!’” remembers Trossell. “We basically had to quit our jobs and go full-time with ScanLAB to make it happen.”

Vimeo Widget Placeholderhttps://vimeo.com/65902863?embedded=true&source=vimeo_logo&owner=5333963

It was a good call. The pair joined a second expedition the following year – both times aboard the Greenpeace icebreaker the

Arctic Sunrise – where they used terrestrial LiDAR scanners to

map the surface geometry of ice floes, capturing the undersides using underwater sonar. The process produced some of the most detailed snapshots of sea ice morphology to date. “A lot of what we delivered to the scientists were spreadsheets of data – that’s what they were interested in,” says Trossell. “But we also had these amazing scans of the ice and it wasn’t until a few years later that we had a chance to use them.”

Those years in between weren’t spent fighting off polar bears or jumping out of helicopters on skis, but slowly building up the business – doing surveys for architecture practices or scanning old manors in the Cotswolds. When they finally did use the scans it was for

Frozen Relic: Arctic Works, an exhibition at the Architectural Association that ran for three months. Trossell and Shaw used their digital surveys to create moulds identical to the ice floes they’d scanned – then filled them with saltwater and froze it. Visitors to the gallery witnessed the suspended floes melting away into drip trays (before being refrozen every two to three days). “We were able to show how this is a dynamic part of the world, but also poke questions about how this is becoming a lost landscape, a relic,” says Trossell.

Unravelling space and time

Vimeo Widget Placeholderhttps://vimeo.com/294369645

Trossell and Shaw first got their hands on a terrestrial LiDAR scanner in their final year at The Bartlett, where it was on loan from manufacturers Faro. At the time (2012) they were about £150,000, the sort of price tag that only those in the petrochemical or automotive industries could justify. They were immediately interested in understanding its limits and borrowed a studio at the Slade School (also part of UCL) for two weeks where they set up experiments to see what the scanner could do. “We thought it was amazing,” says Trossell. “Even at that point, we were wondering if there was a way we could keep on doing this.”

Shaw’s final year project had even looked at the idea of a future in which the city is continuously scanned, like an invisibility cloak, considering how a building might respond to being continuously circulated by autonomous vehicles. They were asked to scan The Bartlett School of Architecture’s Summer Show in 2012 (they’ve scanned it each year since) and later, as ScanLAB took off and The Bartlett underwent a series of building moves – the renovation of

Wates House into

22 Gordon Street, the temporary relocation to

Hampstead Road, and the opening of

Here East – they’ve made scans and animations of those too.

Vimeo Widget Placeholderhttps://vimeo.com/242948294

“Bob Sheil [former Director of the School of Architecture] really drove the project. He wanted to scan the school as it moved. It was an opportunity for them to unravel the space, so we scanned all three sites before and after,” explains Trossell. “It’s quite amazing to see these empty buildings turned into busy, thriving schools.”

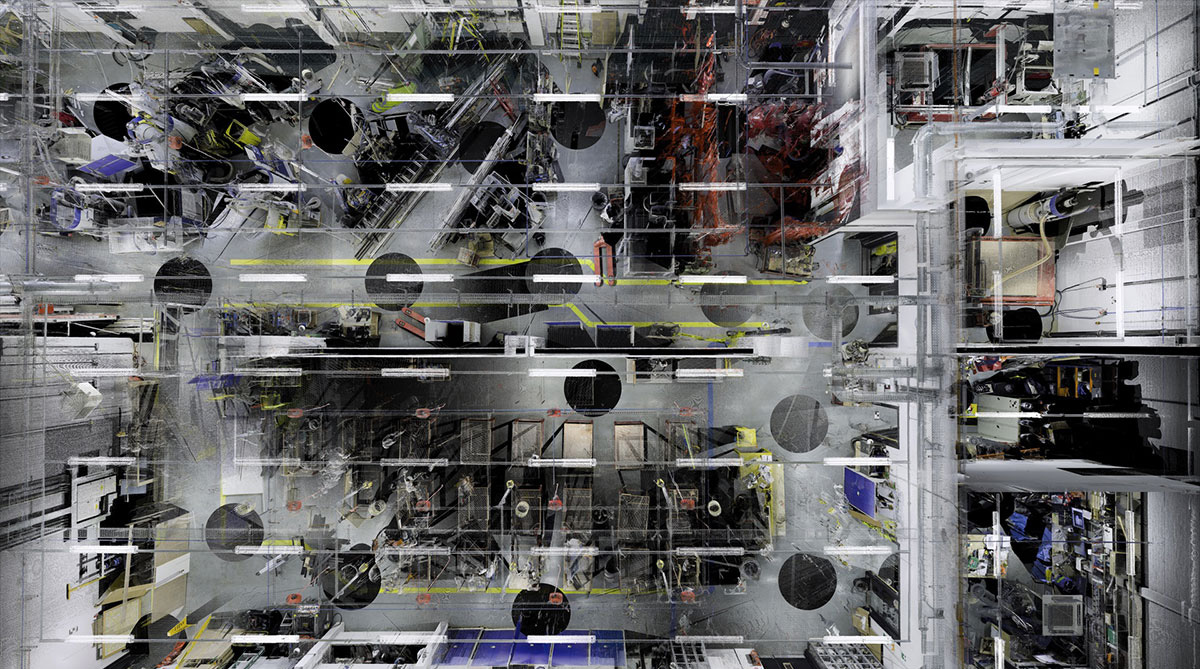

For that project, ScanLAB captured the data and produced the visualisations. Here East, for example, took a team of four people with two scanners five days to scan, then a further two months in the studio to build the animation. But they don’t always work this way. On broadcast projects – they’ve done work for the BBC and National Geographic – ScanLAB will be visualisers; their job being to massage the right things out of an existing LiDAR scan of, say, the jungles of Guatemala, and then put those graphics back into television programmes. “That’s about revealing secrets that traditional cameras could never see, offering audiences new insights and perceptions on spaces and places.”

Vimeo Widget Placeholderhttps://vimeo.com/294379028

Being able to strike this balance – of applying the kind of creative skill the pair learnt at The Bartlett to the data with the often more technical or commercial needs of their clients – turns out to be a welcome challenge, says Trossell. Plus, they always have a personal project bubbling away. In 2016, the ScanLAB team took their equipment into Yosemite National Park with the intention of trying to capture the wilderness just as photographers like Ansel Adams did, only this time using LiDAR. The results of that trip,

‘Post-Lenticular Landscapes’, went on show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the outputs have since travelled, in various forms, to Paris, to Korea as a 360-degree virtual reality experience, and, most recently, to the Royal Academy in London.

“Sometimes we’re artists or photographers, other times we’re technologists, and then sometimes we’re architects,” says Trossell. “That mix certainly reflects the people we have in the room – it’s a really cross-disciplinary studio, and the nature of our work and collaborations demands that. The critical thing is understanding space and thinking about how to navigate and design it.”

Close

Close