Vinnova Case study: A design-led missions approach

6 July 2021

Figure 1: Vinnova’s Street Moves initiative is made possible by scalable and easily deployable wooden structures.

What is the context for mission-oriented innovation at Vinnova?

Operating under the Ministry of Enterprise, Energy and Communications, Vinnova is the Swedish Government’s innovation agency. As a government agency within the Swedish model, it is politically independent and can, for the most part, use its role as a technical and expert-driven agency to set its own direction within the framework set by parliament: to ensure that Sweden’s innovation systems are fit for purpose, in order to enable sustainable growth. This applies to Vinnova’s own culture, and from 2019, with the arrival of new Director General Darja Isaksson, the organisation continued to develop from being an innovation funding agency to an innovation agency. As Hill notes, “Innovation is more than funding, it’s an interactive process.” As a result, the agency continued to move beyond solely funding research and innovation, and began identifying common objectives and mobilizing stakeholders around them.

Sweden’s government departments are relatively well-resourced, robust, and politically independent. This means, however, that there exist a number of different levels of decision-making and responsibility. Taking mobility as an example, national agencies run transport policy and major infrastructure plans, and municipal departments run policy around mobility and planning in towns and cities, whilst public transport is run by regional governments. Public health, which is directly affected by mobility choices in numerous ways, also sits at this regional government level, whereas sustainability and social justice questions can sit at all levels. Together, these factors make coordinated policy decisions difficult and awkward.

While such traditional sector-based approaches allow for the efficient subdivision and management of a problem, they perhaps have emphasized ‘downstream’ operational management over the ability to address ‘upstream’ causes. This can leave problems and opportunities addressed in fragmented fashion, rather than engaging with its complexity in a coordinated, holistic and integrated way.

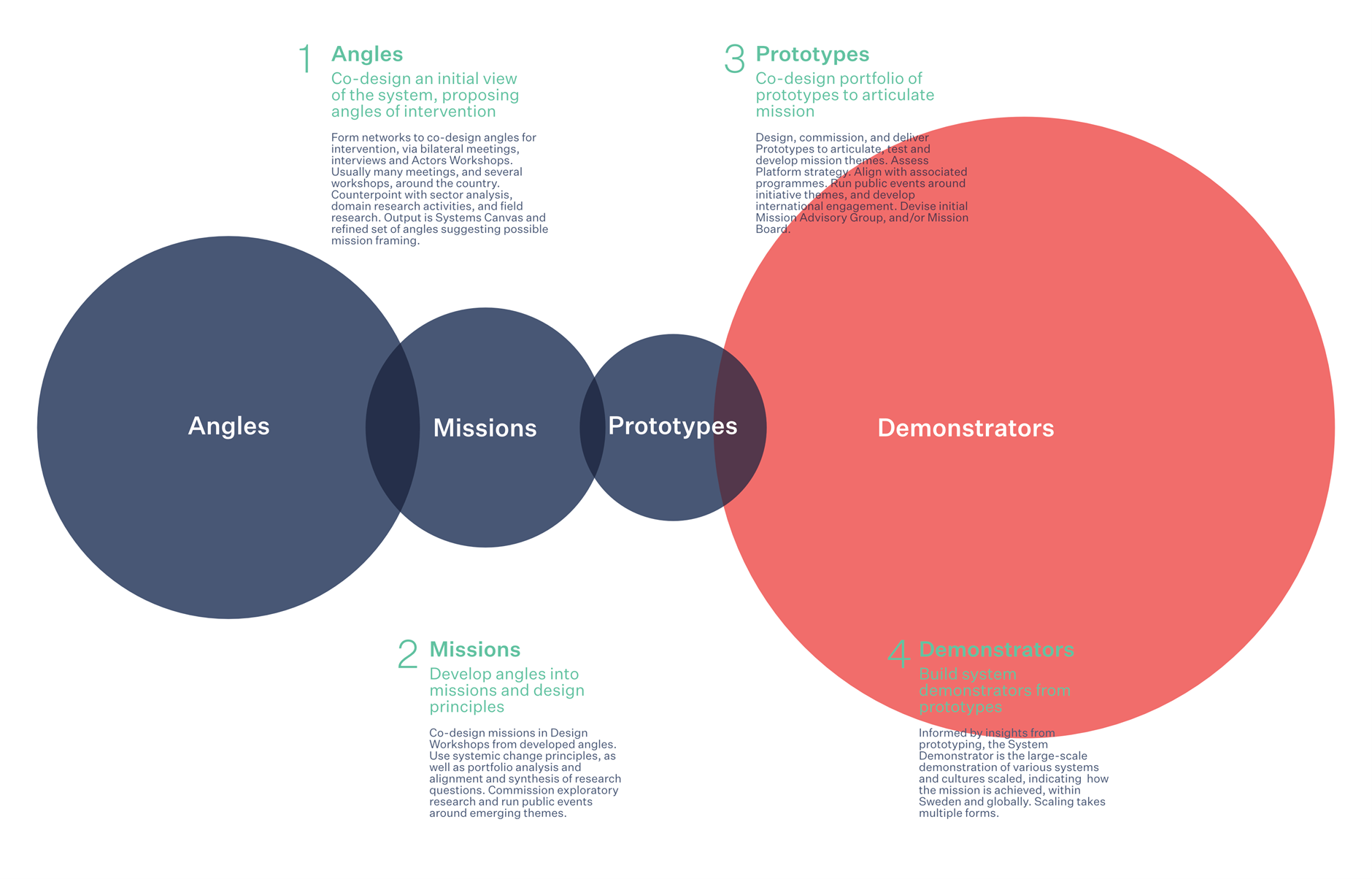

Figure 2: The four steps in Vinnova’s mission-design framework.

Vinnova’s approach to mission-oriented innovation

With their responsibility for stimulating a continual evolution of Sweden’s innovation systems, as well as the EU’s buy-in to the idea of mission-oriented innovation, Vinnova decided to pursue two mission pilots, to develop a preliminary strategy to mission-oriented innovation. Aware that numerous politically-agreed targets were already in place - from the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, to the Paris climate change accord, to Swedish national policies for a ‘fossil free welfare state’ - Vinnova decided to centre its work on two mission themes, or challenges: healthy sustainable mobility and healthy sustainable food. This case study will explore their focus on mobility.

Vinnova’s work around mobility has been deeply participative, thanks in large part to the bespoke design process for mission-oriented innovation developed by Hill and his team at the agency. The mission-design framework is a four-stage process that fuses strategic design, participative cultures and complex systems practice within the overarching framework of mission-oriented innovation. The first stage (see Figure 1) – identifying angles, or intervention or leverage points, in systems language – explores different framings of the problem and opportunities within the theme, derived from engagement practices such as in-depth interactive workshops with stakeholders, interviews and strategic dialogues, desk research and ethnographic research. These produce shared ‘system canvases’, backed up by domain research activities.

With the help of “front-line actors,” including municipal traffic planners, health researchers, and micro mobility startup representatives, Vinnova’s mobility team identified four key intervention points in the mobility system, each of which is likely to contain a clear mission, and each of which balances both demand-led and supply-side innovation, complex systems and cultures, technology and politics, and the potential for place-based systems demonstrators: ‘street’ (context of urban mobility, where multiple systems collide), ‘shop’ (the transforming retail sector, its logistics and touchpoints), ‘grid’ (different ways of powering mobility), and ‘village’ (lower-density, sometimes rural mobility).

The second stage – Missions – expands on each of these clusters of intervention points and works with stakeholders to more accurately frame missions within them. Each of these angles can contain a mission, as it is unlikely that a complex mission theme (like Healthy Sustainable Mobility) can be solved from a single mission. Vinnova sees that an area, like healthy sustainable mobility, will require a portfolio of missions, just as those missions will in turn require a portfolio of projects and other activities. This co-design process identifies the mission lying within these areas, informed by those in the systems, as well as building a network for delivery. This enables a kind of ‘crowding-in’ of expertise and capability around a mission. The first mission to clearly emerge from the process was Streets.

Using design workshops and other participatory activities, the groups coordinated by Vinnova developed an ambitious place-based mission:

“Ensure that every street in Sweden is healthy, sustainable and full of life by 2030.

From a systems perspective, the 40,000 km of streets that already exist in Sweden offered huge potential to scale solutions quickly. A constellation of actors, including large industry players such as Volvo Cars, contributed to design workshops, with the intention of collectively identifying a portfolio of projects that could support the street mission.

The third and fourth stages – Prototypes and Demonstrators, respectively – design and deliver a portfolio of prototypes and public interventions that begin to concretely deliver on the mission. Prototypes are used heavily as real interventions into real streets, thereby testing solutions in real situations. The prototyping stage saw the most involved and valuable form of citizen participation: public interventions through prototypes stimulated discussion, debate, and feedback that continue to directly shape and co-create the form that the mission is taking.

As well as being participative, Vinnova’s missions are place-based. As the Mission-oriented Innovation Policy Observatory (MIPO) at Utrecht University has written, “place-based missions focus on a specific place, like school food cafeterias or streets where a range of both problems and solutions come together. By narrowing down the place-based scope, it is possible to maintain the full complexity in terms of problems and solutions.” Furthermore, by focusing on streets, Vinnova’s mobility mission developed a new street-centred governance model, which allowed traffic, public health, and police departments – to name a few – to break out of their silos and collaborate in new ways.

Figure 3: The Street Moves initiative is in the process of expanding to more cities in Sweden.

What solutions are emerging as a result of the missions approach?

Initially a set of prototypes, Vinnova’s mobility team designed and is now scaling its Street Moves initiative, a set of easily-deployable and modular wooden structures that take the form of benches, bike stands, or gardening plots.

With prototypes having already been deployed in Stockholm, Street Moves has allowed communities to become directly involved in reshaping their neighbourhoods. The design of each street is inspired by workshops and interactive planning sessions with local residents, including shop owners, parents, or schoolchildren. Local communities in Stockholm are already expressing their satisfaction: of the 322 people surveyed about 70% were positive with hardly any negative responses. Following further successful expansions to Gothenburg and Helsingborg, Street Moves is also spreading to Umeå and Malmö.

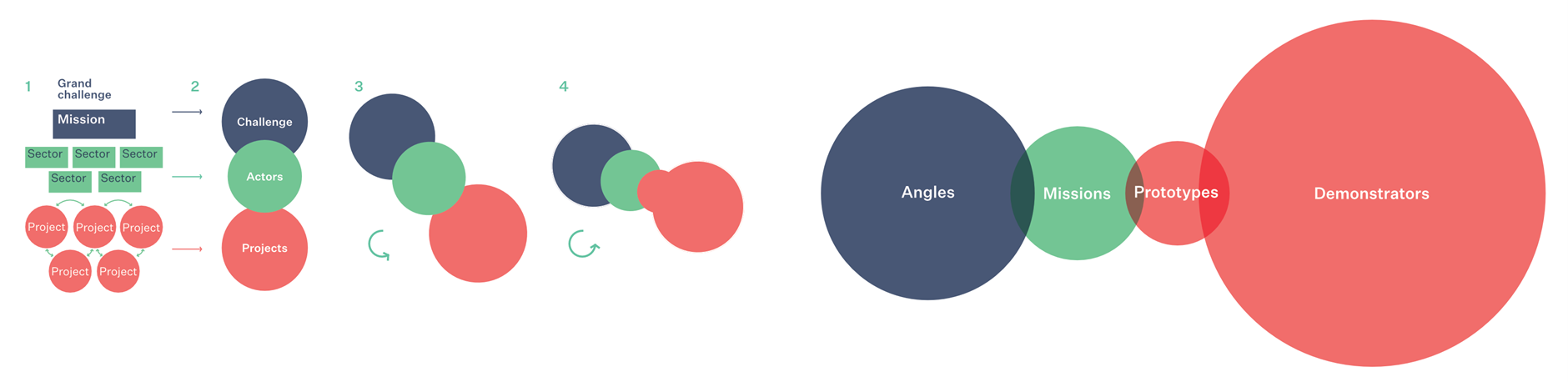

Figure 4: The Vinnova team turned the mission roadmap structure on its side, to demonstrate how it can be transformed into a participative process.

What challenges does Vinnova face in implementing a missions approach?

Vinnova has managed to organize this entire mobility mission with a relatively small budget, which was primarily dedicated to low-cost workshops and late-stage prototypes. Hill explains that, much like using kindling to start a fire, the agency’s budget initiated the project; eventually, however, it must be incorporated into existing systems and budget structures. This speaks to a broader challenge around design-led missions: if the mission does not receive high-level political or private-sector buy-in and is therefore not integrated into existing structures, then it will unlikely survive on its own legs.

A further challenge is that measuring the non-monetary impact of initiatives such as Street Moves will be difficult. Costs that municipal governments expect to incur, including foregone parking space revenues, are easily measured, while the resulting benefits, including public health and wellbeing savings, environmental benefits, or maintenance benefits are difficult to take into account. New forms of evaluation and assessment must, therefore, be developed to bolster the legitimacy of these missions.

Close

Close