Explainer: What is COP26?

13 April 2021

At a glance

- The Conference of Parties (COP) is the annual meeting of the 196 countries plus the European Union that have joined the UN's Climate Change Convention. The 26th COP (COP26) will take place in Glasgow in November 2021.

- Climate change is a global problem with unequal impacts – addressing climate change is a matter of justice.

- Progress has been slow. Until now, few countries have taken strong action – and current commitments to reduce emissions are still far from sufficient.

- But there is now a clear destination shared by the whole global community. Action is increasing in more and more countries and at many levels of society. Momentum needs to build rapidly – and there is a role for everyone, from local to global scales, in making this happen.

What is the problem?

Addressing climate change is a matter of justice – but also politically contested

Climate change disrupts ecosystems and threatens to alter fundamentally the conditions for life on our planet. It affects everyone – but is likely to hit the poorest first and hardest. Addressing climate change involves reducing greenhouse gas emissions to limit temperature rise (mitigation) as well as preparing for the consequences of living on a warmer planet (adaptation). Action on all levels, from global to local, is required to make sure this happens quickly and in a just manner, with the responsibility for taking climate action, as well as the benefits of doing so, distributed fairly across and within countries.

In the context of growing scientific evidence, the United Nations (UN) adopted its Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1992, which aims to ‘prevent dangerous anthropogenic [human induced] interference with the climate system’. The Conference of Parties (COP) is the annual meeting of the 197 parties that have joined the Convention. The first COP took place in Berlin in 1995. The 26th COP – COP26 – will be hosted in Glasgow in early November 2021.

Although the need to act to address climate change is clear, agreeing on exactly how to act has never been easy. Most human activities are dependent in some way on technologies and processes that create greenhouse gas emissions. Unprecedented systemic transformations are required to disrupt these dependencies. Countries have been reluctant to make such changes, fearful of the economic and political costs, and the implications for their economic competitiveness.

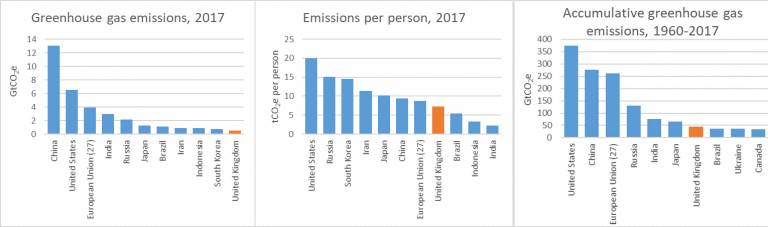

On the global level, discussions have revolved primarily around two issues: whether or not states should be subject to legally binding obligations; and how to divide responsibilities for emission reductions in a fair and equitable manner. Should those nations with the highest overall emissions take the lead? Or should it be those nations with the highest emissions per person? Should it be the richest nations, whatever their current emissions? What should be the role of those with most historic responsibility for past emissions? These are complex political questions.

The top 10 global highest emitters plus the UK (left); the same top 10 global highest emitters plus the UK arranged in order of their average emissions per person (centre); and the top 10 largest historical emitters since 1960, including the UK (right). [Units: 1GtCO2e is 1 billion tonnes of CO2-equivalent (tCO2e) emissions, where all greenhouse gases are converted to their equivalence to CO2 in terms of their Global Warming Potential]. Graphs drawn using data from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), available at https://www.climatewatchdata.org/

What are the key characteristics of the problem?

The Kyoto dilemma

The first attempts to implement the UN Climate Change Convention led to the adoption of the Kyoto Protocol at COP3, in 1997. The treaty agreed legally binding emissions reduction targets for developed countries, but set no targets, either binding or voluntary, for developing nations. It included options for the developed countries to fund emissions-reducing projects in other countries, and count these emissions reductions towards their own targets. In the end, however, fears over the economic costs of mitigation meant that the developed nations agreed to targets which amounted to an overall reduction of greenhouse gas emissions of just 5% below 1990 levels in the period 2008-2012. In spite of this relatively modest goal, the US never ratified the protocol, and Canada was later to withdraw from it, further reducing the share of global emissions covered by the treaty.

Given these limitations, efforts to find a successor treaty began shortly after the Kyoto Protocol entered into force. It was hoped that these efforts would lead to a legally binding agreement that covered all countries – not just those identified as ‘developed’ by the original Convention in 1992. However, some nations still expressed resistance to the idea of signing up for legally binding targets, and the issue of who should take the lead on emissions reductions remained highly divisive. There was also disagreement over the wider remit of a future treaty, with developing countries calling for increased attention to issues of financial transfers, development and the need to adapt to the impacts of global warming.

COP15 at Copenhagen in December 2009 was intended to be a moment of hope, where a new globally comprehensive and legally binding treaty would be agreed. It was not to be. The tensions and disagreements about appropriate contributions and responsibilities could not be corralled into a single treaty. With negotiations on the point of collapse, a small group of nations hurriedly hammered out a political agreement – the Copenhagen Accord.

World leaders and diplomats at COP15 in Copenhagen, 2009. Image credit: Official White House Photo by Pete Souza on flickr

What is the solution?

The Copenhagen interpretation

Despite falling well below the expectations for a global treaty, the Copenhagen Accord planted some important seeds. It articulated a goal of holding the increase in global average temperature below 2°C, and called for future consideration of strengthening this target to 1.5°C. It set a target of $100bn per year of climate finance for developing countries by the year 2020. And, in the absence of collectively negotiated emissions targets, it asked all parties, developed and developing, to provide a list of voluntary planned mitigation actions and targets.

With no quantified emissions targets, and no sanctions, the Accord was widely condemned as insufficient in its time. But with hindsight this list of hasty face-saving compromises can be seen as the first draft of a new approach, which was developed over the next few years, and adopted – to some fanfare – at COP21 in Paris, in 2015.

The Paris Agreement expresses the shared ambition of all parties to keep global temperature increase ‘well below 2°C’, while ‘pursuing efforts’ to limit it to 1.5°C. It attends to the importance of adaptation to the effects of climate change, as well as avoidance of greenhouse gas emissions (mitigation). It also calls for developed countries to provide financial resources to help developing countries both with mitigation and adaptation. Like the Copenhagen Accord, the text of the agreement does not specify emissions reduction targets, either globally or attributed to countries. Instead, the Paris Agreement sets up a process, which can be summarised as ‘pledge, review and ratchet.’

Under this process, each country is invited to come up with its own ‘pledge’ - a nationally determined contribution (NDC) – detailing how it intends to act on climate change. Like a progressive parent asking a child, “how long do you think you should be spending on your homework?”, the Paris Agreement provides no obligations and threatens no consequences, but rather offers guidance based on broad principles and expectations. NDCs are expected to reflect the ‘highest possible ambition’ and be progressively strengthened over time. While all countries must submit NDCs, developed countries should continue to take the lead and provide support to countries that need it.

The progressive strengthening of NDCs is encouraged by a five-year cycle of ‘review’ – the global ‘stocktake’ – followed by revision and resubmission – or ‘ratchet’. The purpose of the stocktake is to consider whether the submitted NDCs collectively put the world on the right path for achieving the goals of the Agreement. NDCs will then need to be resubmitted taking this review into account. A trial run of the first stocktake took place in 2018, with countries asked to submit revised NDCs by the end of 2020. The first full stocktake is scheduled for 2023, with NDCs to be resubmitted in 2025; and every five years thereafter.

The flexibility of the Paris Agreement enabled it to be adopted by almost all countries of the world. Although the United States formally withdrew from the treaty in 2019, President Joe Biden reversed this decision shortly after his election. As a result, the Agreement covers the vast majority of the world’s emissions – this alone is a significant and genuine breakthrough in international climate politics.

The Paris Agreement is adopted at COP21. Image Credit: UNclimatechange on flickr

What is stopping the solution being implemented?

A step in the dark

But, at the same time, the Paris Agreement is a step in the dark. With no top-down negotiated targets or sanctions, and only guidance based on expectations about what kind of ambition countries should aim for, there is a clear risk that countries will leave it to others to act. Indeed, the first round of NDCs, even if fully implemented, would still lead to an estimated temperature rise of at least 3°C by the end of the century. And time is running out – scientists warn that we must halve global emissions within the decade, and continue with steep reductions thereafter, if we are to put the world on an emissions pathway consistent with the relatively ‘safe’ limit of 1.5°C.

How can these barriers be removed?

Pledge, review and ratchet – the work starts here

These challenges are real, and allow no room for complacency. The innovative ‘bottom-up’ approach of Paris is far from being risk-free. On the other hand, experience had already shown that holding out for a global treaty with top-down targets was no option at all.

The results of the initial stocktake were disappointing, but not unexpected – in fact they were anticipated by the ‘pledge, review and ratchet’ process. More positively, the 191 NDCs submitted represent a very high rate of engagement with the process. Further, following the 2018 stocktake, 48 new or revised NDCs have been submitted. Admittedly, these revised submissions amount to only a 2.8% reduction by 2030 compared to the countries’ original NDCs, and are consequently still a long way off course for 1.5°C or even 2°C. However, these developments show the process is beginning to work – albeit with a long way to go. Many more parties should submit revised NDCs this year. COP26 will be an important first chance to analyse critically countries’ responses to the review and ratchet process.

COP26 will also be a chance to discuss a number of other mechanisms that could support the transition to a low-carbon, climate-resilient world. Should countries be allowed to ‘offset’ some of their emissions by funding emissions reduction in other countries? Should vulnerable countries be compensated for climate change impacts that are already ‘locked in’ and cannot be adapted to? What more needs to be done to scale up climate finance for developing countries, and to increase international cooperation and the transfer of technologies and knowledge? What is the role of nature-based solutions in taking carbon out of the atmosphere, for example through the planting and growing of trees? Each of these areas will also demand careful attention to justice – making sure that the low-carbon transition does not simply reinforce existing inequalities between and within countries, but instead contributes to bringing about a fairer world.

Conclusion

As we approach thirty years since the adoption of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, there is justifiable frustration and anger at the slow pace of action, and the injustice of this. This is reflected, for example, in the youth-led climate strikes that swept around the world in 2019 as well as the formation of more radical activist movements such as Extinction Rebellion.

Protesters around the world are demanding climate justice. Image credit: Markus Spiske on Unsplash

Valid and important though this frustration is, the political complexity of achieving a global climate change agreement is also a fact. And though the pace is frustratingly slow, the political achievements are real.

There is a kind of hopeful alchemy to the Paris Agreement – a commitment to start moving forward, even with very small pledges, in the belief that the movement itself will generate larger pledges further on.

As the Paris process moves forward, it can gather momentum and stability from multiple levels. Certainly, an overarching global framework negotiated by nation states is essential. But just as crucial are the actions of people at all scales – national, regional, sub-national (cities and local communities); and from all sections of society. This is because, first, in international negotiations, nation states are playing what has been called a ‘two-level game’; they are negotiating with other states, but also with a domestic audience. The stronger the support at home, the more they are empowered to push for in the negotiation.

And second, because the technological and social innovation that is occurring at multiple levels - in demonstrating the viability of the transition - can substantially alter the political context in which the negotiations take place. Leadership shown by states, cities and regions, by progressive companies, indigenous communities and other civil society groups, as well as by individual citizens, can catalyse and accelerate novel solutions that nation states can take up, adding further momentum to the process.

So get engaged with the COP process. This will make it more likely that your government will stick to its commitments, and encourage it to take stronger action – you can find your country’s NDC here. But you can also support your country, and hence the global effort, by taking action at any level you can. Building global momentum requires leadership at all levels – home, school, workplace, neighbourhood, city, region, as well as the national level.

Climate change is a complex problem, and progress has been frustratingly slow. But there is now a clear destination shared by the whole global community. Building on decades of groundwork, action is increasing in more and more countries and at many levels of society, from the grassroots up. The world is moving. We can all be part of that movement.

Key references for further information

A full account of the development of international climate negotiations is provided in “The Long Road to Paris: The History of the Global Climate Change Regime”.

A summary and infographic of the main elements of the Paris Agreement is available here.

Close

Close