Exhibition: Vulnerability, Infrastructure, and Displacement

5 August 2019

The IGP's 'Vulnerability, Infrastructure and Displacement' exhibition explored the symposium themes through a range of media. Artists and researchers mapped infrastructural change in Lebanon, envisioned improved public services and grappled with the toxification of the landscape.

CatalyticAction: Participatory Spatial Intervention: Addressing vulnerabilities through infrastructure

As a part of the project Public Services and Vulnerability in the Lebanese Context of Large-Scale Displacement, CatalyticAction played a leading role in implementing a Participatory Spatial Intervention in the refugee-hosting town of Bar Elias in the Beqaa Valley. Over the course of one year process, they liaised with the municipality and other important actors, trained Citizen Scientists representing the local Lebanese, Syrian and Palestinian communities, and engaged the wider public through participatory research. Local researchers and workshop participants identified the main vulnerabilities different residents were exposed to and proposed ways of addressing these through small-scale infrastructural interventions. These proposals were then turned into professional designs and, following another round of consultations, built along the main road of the town. The outcome is a significantly changed urban landscape along a particular stretch of road: the hope is that green spaces, seating areas, access ramps, speed bumps, and spaces for play will make the town safer, more accessible and more inviting for all residents of the city to share. Read more about the specific elements of the Participatory Spatial Intervention here.

Catalytic Action are a charity and design studio that work to empower communities through strategic and innovative spatial interventions. Their story began in 2014, when they supported refugee children in Lebanon through the provision of safer and stimulating educational spaces. Today, they are still working with the most vulnerable communities around the MEA region and Europe to improve and shape together the quality of their built environment. They focus on their process rather than just the final product. To enhance community resilience, they adopt three interconnected phases throughout the development of each project. Their work aims at alleviating poverty and inequalities, catalyzing positive change.

Diala Makki, Mona Harb and Mona Fawaz: Actors, Governance and Modalities of Sanitation Services: Informal Tented Settlements in Zahleh (Lebanon)

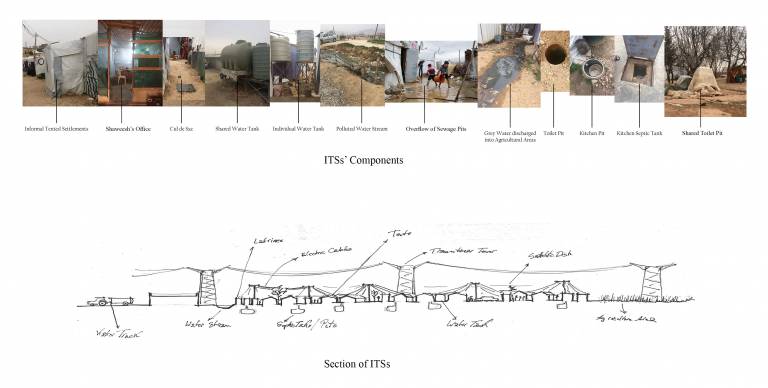

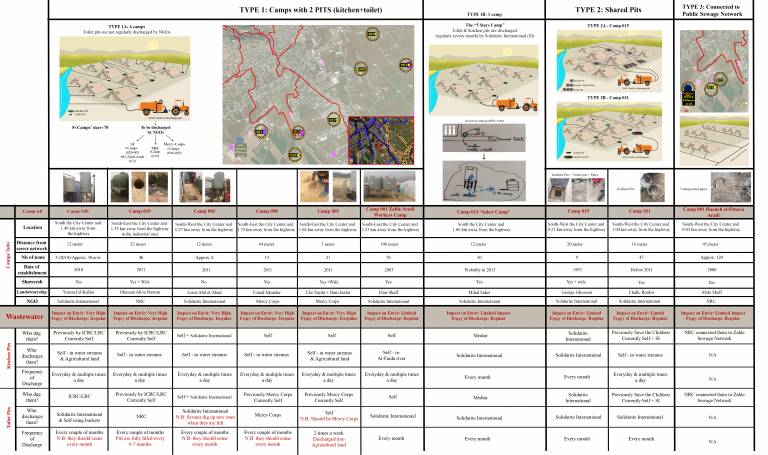

Since the 2011 war in Syria, Lebanon hosted the highest number of refugees per capita. Access to water and wastewater services depends, for these refugees on the type of housing where they live. Syrians living in residential buildings share the situation of the Lebanese host community and benefit from pre-existing arrangements and infrastructures. As for Syrians in Informal Tented Settlements (ITSs), accessing basic services is a hurdle and they do not have direct access to water, wastewater or electricity. Thus, the modes through which Syrian refugees access sanitation services are further fragmenting and “hybridizing” service provision. They are typically unable to connect to public services’ main networks since infrastructure projects in Syrian camps are discouraged by the Lebanese government, which claims these would impede the refugees’ willingness to return and would further lead to their naturalization and permanent residence in Lebanon. Therefore, ITSs rely on an assemblage of systems managed and operated commercially and by self-help through formal and informal actors. These actors range between reluctant local governments, international organizations and NGOs typically operating in “crisis/relief” mode, landowners, intermediaries (shaweesh, other), and refugees themselves. Although this system often responds to the immediate dire needs of refugees, it suffers from many shortcomings, the most prominent of which is environmental pollution that results from sewage seeping into the underground water table and the disposal of untreated sludge in the rivers.

Based on fieldwork in 10 ITSs in the valley of Zahleh (Lebanon), the thesis identifies three types of wastewater systems implemented in these ITSs: (1) ITSs with two wastewater pits per tent: one for black water (toilet) and one for grey water (kitchen); (2) ITSs with shared wastewater toilet pits; and (3) ITSs directly connected to the network. This research unravels the clear juxtaposing of state-based supply and alternative supply of private stakeholders, INGOs and refugees themselves which shows that both systems of service delivery are connected technically and economically to the legal world. This complicates the relationships “between the legal and the illegal, the legitimate and the illegitimate, authorized and unauthorized” (Roy, 2011).

Mona Harb is Professor of Urban Studies and Politics and Chair of the Department of Architecture and Design at the American University of Beirut. She received her PhD in Political Science in 2005 from the Institut d'Etudes Politiques at Aix-Marseille (France). She is the author of Le Hezbollah à Beyrouth (1985-2005): de la banlieue à la ville (Karthala-IFPO, 2010), co-author of Leisurely Islam: Negotiating Geography and Morality in Shi'ite South Beirut (Princeton University Press, 2013, with Lara Deeb,), co-editor of Local Governments and Public Goods: Assessing Decentralization in the Arab World (Beirut: LCPS, 2015, with Sami Atallah), and more than seventy-five journal articles, book chapters, monographs, essays and technical reports. Her ongoing research investigates local governance and refugees, urban activism, and youth in Lebanon.

Mona Fawaz is Associate Professor in Urban Studies and Planning and the Coordinator of the graduate programs in Urban Planning, Policy and Design at the American University of Beirut (AUB). She is also the program coordinator of the Social Justice and the City program, a platform based at the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at AUB which aims to formulate an agenda for research, mobilization and policy advocacy that establishes a partnership between scholars, policy-makers, and activists working towards more inclusive cities in Lebanon. Fawaz was a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute of Advanced Studies at Harvard University during the 2014/15 academic year.

Fadi Mansour: Dreamland

In the aftermath of a prolonged trash crisis in Lebanon, solid waste is used as filling material into the creation of new territories on the sea. In the purpose of coastal regeneration, an old dumpsite hill is dismantled and its toxic matter is spread onto the sea as the bottom layer of this new land formation. This operation releases a forty-year-old history of toxicity into the surrounds leading to an intensified environmental degradation while the directly visible end product is a valuable stretch of real estate. By way of countering the perspective of the polished architectural product, the video portrays the ecological transformation by investigating the extent of sea pollution on invisible marine biomass. As the scale of the toxic spread abounds the visible and sensorial impact at the site of the landfill, the vulnerability of affected bodies - human or nonhuman - stretches toward uncertain futures. Elaborating on this futurity, “Dreamland” questions the relationship between bodily materiality and toxicity. Whether soil, skin or water, matter interacts with both flows of capital and flows of toxicity, in a seemingly choreographed entanglement with machines.

Fadi Mansour is an artist and researcher based in Beirut. He graduated from the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths University of London in 2017 and the Architectural Association Diploma School in 2009. His research work and visual art practice lies at the intersection of techno-capitalism, colonial violence and queer ecologies. His writing was published in Jadaliyya, ArteEast and the Sursock Museum Publication. His audio-visual work was exhibited and screened at Goldsmiths University, the Sursock Museum, the Goethe Institute, and Ashkal Alwan.

Jessika Khazrik: When We Were Exiled, Water Remained

In 1956, the Lebanese Ministry of Planning issued a decree to canalize the Beirut River. That same year, the state drew the borders of administrative Beirut, limiting its northern line to the river bank. Using the river as a “natural border” that re-enforces a homogenous centralized capital, the inhabitants of the area – with the majority being Armenian, Palestinian and Kurdish asylum seekers – were displaced again.

“When We Were Exiled, Water Remained” is the script of a play that takes the arid course of the canalized river as its stage to festively question the buried political histories that have, along the years, allowed the transformation of the river into both an exilic border zone and a dump. While probing the exploitative instrumentalization of the notion of truth in Lebanese jurisprudence, this play questions surviving mechanisms of exclusionary and perjurious state-building in relation to the present trash, infrastructural and displacement crises. Oscillating between documentary theatre, history of science and ritual, the site-specific play invites inhabitants, witnesses, workers/performers from all of the fields of urban research, science, music and law to reclaim the river as a public site of movement, circulation and attestation.

Read the script here.

Merijn Royaards: City of Impulse

The Egg is a long-abandoned Brutalist cinema and commercial complex located in the heart of Beirut, just south of Martyr Square along what was the front line between the Eastern and Western parts of the city during the civil war (1975-1990). As a consequence, the structure is ravaged with bullet holes and has large parts shoaled off by sustained artillery fire.

“City of Impulse” is a filmic edit of slow walks through The Egg, recording the crumbling building, its visual scars, the remnants of what was before and after and the fast-changing urban fabric that surrounds it. The film’s soundtrack is a hyper-real version of the city as it sinks into and bounces off the structure. Sounds morph from deafening streetscapes to hollow flutter echoes inside the actual cinema. A subsonic blanket of heavy traffic fused with high-pitched bird-song as the base of the destroyed office tower fades to echoic and cavernous drips and clangs inside the flooded underground car park. Spatially and psychologically distinct parts of the city are layered, fused and laced with the otherworldly acoustics of The Egg’s physical structure.

Mustapha Jundi: Shoreline and Volumetric Sovereignty

The Lebanese shoreline is a site of crisis with multiple modalities; a hierarchy of intensities collapsing different spaces and forces. It stands as one of the last frontiers of the battle between private accumulation of capital and the public realm, positioned in relation to the politics of climate, weather and extraction. The project considers the city's edge between land and sea as fluid frontiers where the entanglement among various forces is manifested. It transforms the cartographic boundary line between land and sea along the coast into a volumetric and atmospheric conflict between climate, property and materiality.

“Shoreline and Volumetric Sovereignty” focuses on the atmospheric layer of the shoreline. This is examined through the observation of the meteorological department in Lebanon and the exposure of the various devices constituting the weather monitoring metrics. The cartography of the line is reconfigured into a network of natural elements monitored through different technologies. Examined as an extension of the colonial project of property metrics on the shore, which were introduced during the French mandate, the objects constitute an essential part in the genealogy of weather monitoring in the country, more specifically in the post-war infrastructural reconstruction project. Prediction and speculation crystallize in the inevitably changing boundary of the shoreline.

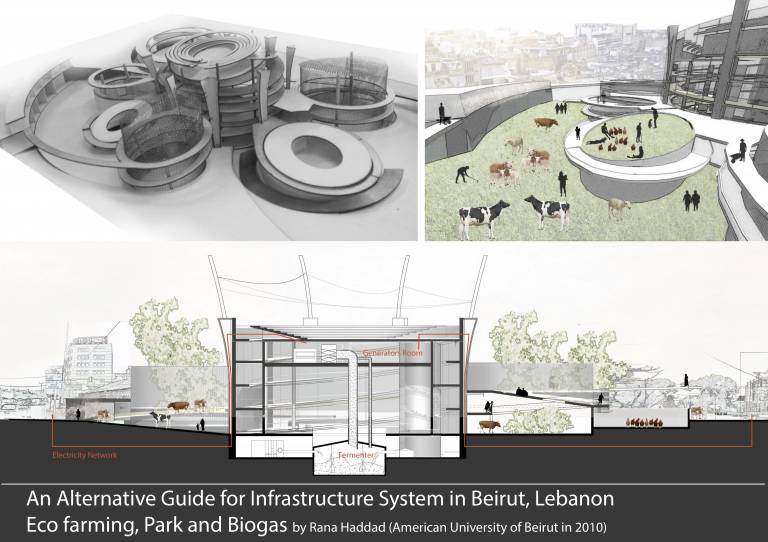

Rana Haddad: An Alternative Guide for the Infrastructure System in Beirut_ Eco Farming, Park and Biogas

One of the major flaws in the Infrastructure system in Lebanon is power cuts. Even in the capital Beirut, electricity cuts can last for six hours daily. Lebanese people rely on diesel generators as an alternative. They are a major source of pollution for the city and each neighborhood ends up having private providers that deliver electricity through these generators. They have gained so much control since they provide the only alternative solution and hence have become the “Cartel of Power”.

My project is an ecological friendly and profitable alternative to provide electricity to neighborhoods in Lebanon especially in Beirut. It is located in Bourj Hammoud, one of the densest areas in Beirut with no parks and little greenery. The project works as a biogas facility, a local farming and a park all in one entity. Animals like chicken and cows have access to open green spaces. They are treated through more humane practices and as sentient creatures. People would then enjoy higher quality organic and local produce. The animal waste is collected and put in the fermenter of the biogas. Gas is harvested and through a cogenerating system, electricity is produced as a green eco-friendly substitute to compensate for the power cuts. Another advantage of the facility is that people could use it as a park, be closer to nature, animals and learn more about farming techniques.

This sustainable model is an example of how on a neighborhood scale, small projects in Beirut can bring about positive bio solutions to major infrastructure problems.

Close

Close