Professor Laura Vaughan's spatial analysis of historical maps has uncovered a depth, nuance and texture to the city often missing from pure statistical data.

Section of Charles Booth’s 'Descriptive Map of London Poverty', 1889. This section of the East End illustrates the pattern of marginal separation of poverty from relative prosperity. Source: 'Booth, Life and Labour of the People'. Credit: Cartography Associates

“There are some deep structures in cities that are very hard to shift, such that poverty areas that were apparent in Charles Booth’s London 120 years ago continue to persist.”

Booth’s famous maps, documenting 19th century patterns of poverty in London, were foundational when it came to Vaughan writing her 2018 book Mapping Society, which pulls together two decades of her research to offer a spatial reading of the social patterns of major cities – such as London, New York and Chicago – over the past 130 years; from the distribution of ethnic quarters and poverty to the spatial cultures of street gang activity and the persistence of health problems.

What emerges through her space syntax analysis of historical maps is a depth, nuance and texture that can be missing in data that’s purely statistical. “The importance of the spatial analysis of historical data is not to be underestimated,” says Vaughan, who is also Director of The Bartlett School of Architecture’s pioneering Space Syntax Laboratory.

Going beyond simply reading data from a chart or map, to a deeper analysis of geographical patterns, she adds, unveils the long-term impact of decisions taken in the past and points to the significance of urban design and planning as a practice for shaping cities over time.

For example, she says, segregation in cities is shaped by different forces today compared with Booth’s era. “While in the past, we might create types of housing that formed isolated pockets differentiated by class, race and religion, today a combination of market forces and the speed of change are leading to sharper divisions between the rich and the poor than ever before.”

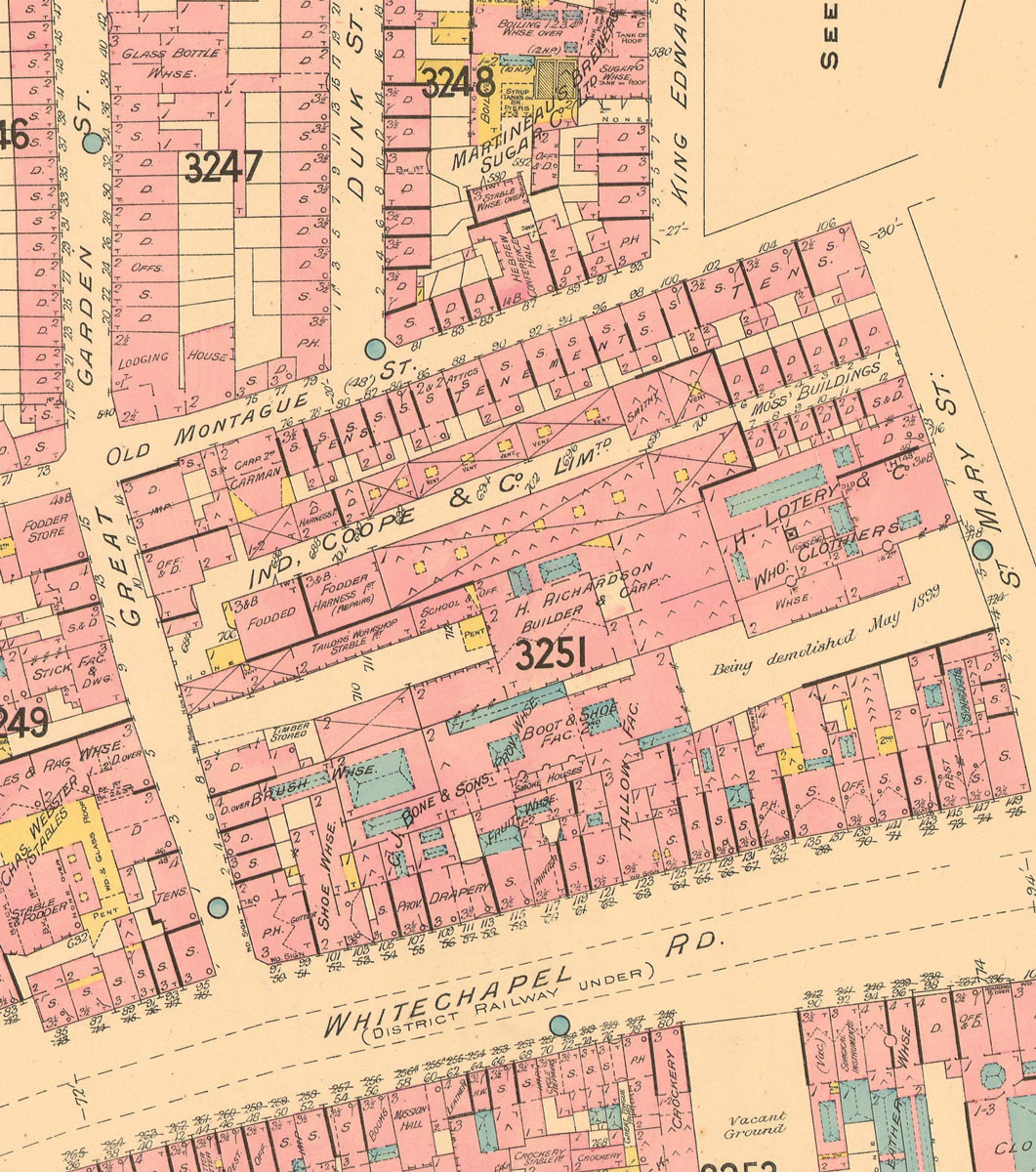

Section of the Goad Plan of 1899, sheets 323, showing the diversity of land uses present at the time of the Booth surveys, illustrating the spatial juxtaposition of economic, cultural, communal and religious activity in London at the time. Credit: Crown copyright and Landmark Information Group

Unveiling rules about how cities work

Spatial analysis also means a researcher can consider the commonalities and interactions between specific trends, and control for spatial effects when analysing social patterns – unveiling fundamental rules about how cities work.

“For example, if we label an area as segregated, we account not only for it containing a particular mix of population, but also the environment that shapes opportunities and might create barriers, [such as] environmental degradation or constraints on mobility,” Vaughan says.

“In a recent study I conducted with EU-funded scholar Jonathan Rokem, we found that patterns of ethnic and social segregation in cities such as Paris, Stockholm or Jerusalem are not just about where you live – what is really important is mobility. The city itself is an important factor in shaping an individual’s opportunities, economically and socially.”

Vaughan’s expertise in this field means she has helped shape London’s planning policies and British transport design decisions, as well as advising the government on such issues as how urban design could be used to combat social isolation and to tackle uneven access to healthy and unhealthy food.

What has also emerged through her research is the political salience of mapping exercises: “A side product of this inquiry has been the discovery of the extent to which social cartography is frequently used not only as a tool for communicating information, but also for propaganda, to collate evidence or to support scientific argumentation.” It’s their less prevalent use, as an analytical tool, that Vaughan’s book champions.

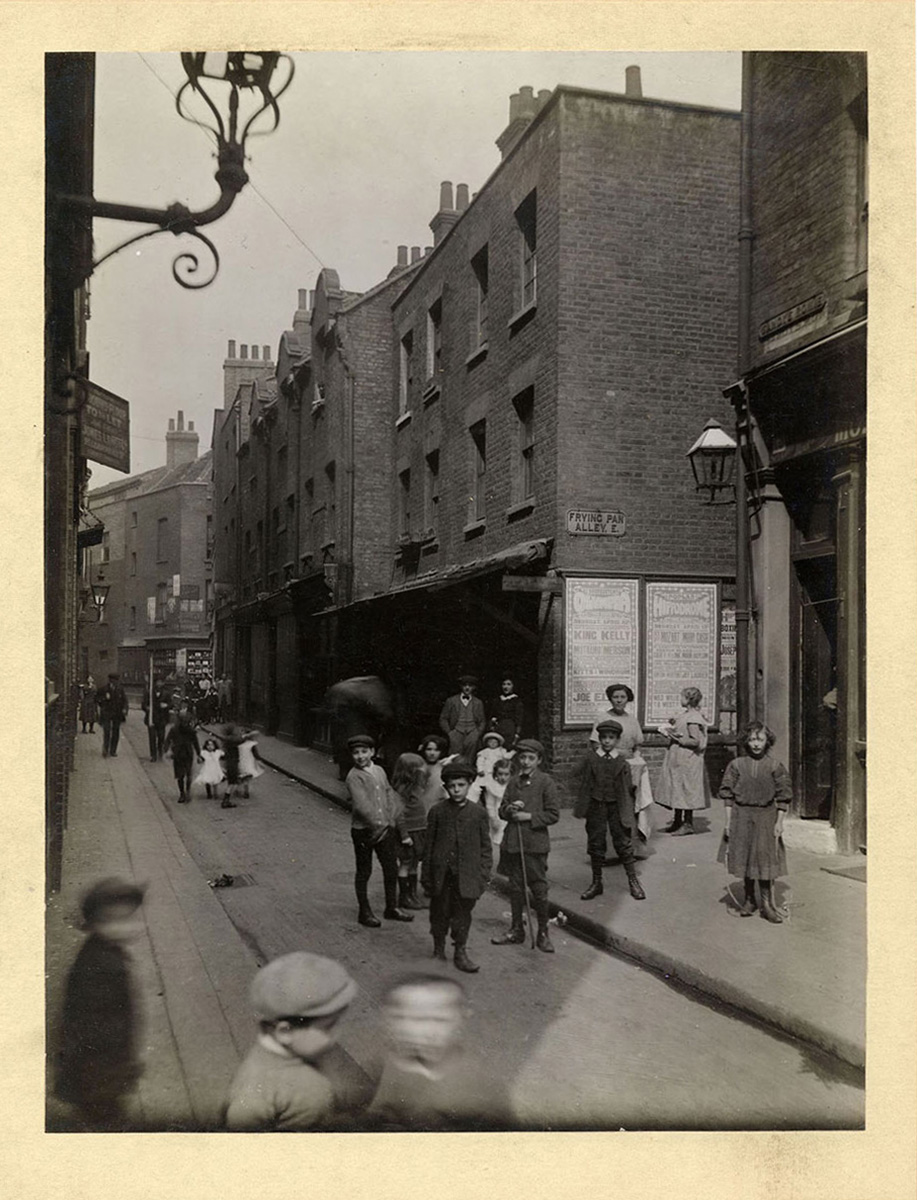

Photograph of Sandy's Row, corner of Frying Pan Alley, taken on Saturday April 20th 1912 by C.A. Mathew. The alley was situated in the heart of the Jewish neighbourhood in London’s East End. The socio-spatial patterning of immigrant settlement is discussed in Professor Vaughan's book 'Mapping Society'. Credit: Bishopsgate Institute

Laura Vaughan is Professor of Urban Form and Society at The Bartlett School of Architecture

Close

Close