How can we make technology work for humans? Eleni Papadonikolaki reflects on what the built environment could be like if we asked a different set of questions.

'Tunis: section of the bridge-town above Medina' variant with colour from 'La Ville Spatiale' projects by Yona Friedman (1959). Credit: Yona Friedman / www.yonafriedman.nl

Can ‘digital transformation’ mean something different than the way it is often talked about today?

We typically don’t discuss how we can make human lives better. What I mean by that is, despite all of the technology around us, we don’t understand how we can improve the quality of human life – only how we can make it more efficient: how we can reduce our commutes or automate our emails, for example. The way that we organise work, and the very nature of ‘work’, aren’t really changing. So I’m wondering to what extent we can repurpose or re-channel all of the time and energy that we spend developing new technologies for efficiency, into changing the ways that people interact with nature and one another to create societies.

Have we always been asking the wrong questions of technology?

Many architects and thinkers of the post-World-War-2 era envisioned the intensive development of technology as a means to creating a better human and to radically transforming their lives. Yona Friedman designed and wrote about how architecture and space could be designed, built and used by citizens themselves. He looked at architecture as a participatory process where all humans could build something – anybody could do an ‘architectural act’ – they could shape the environment around them in order to be happy. He had a down-to-earth and inclusive view of architecture driven by constant curiosity and playfulness.

Takis Zenetos’ ‘Electronic urbanism’ envisioned connected flexible, modular, nature-friendly and human-centred structures, with ubiquitous telecommunications networks to connect humans and provide them with time and space. This was opposed to top-down systems; he believed it would allow for bottom-up communities to emerge.

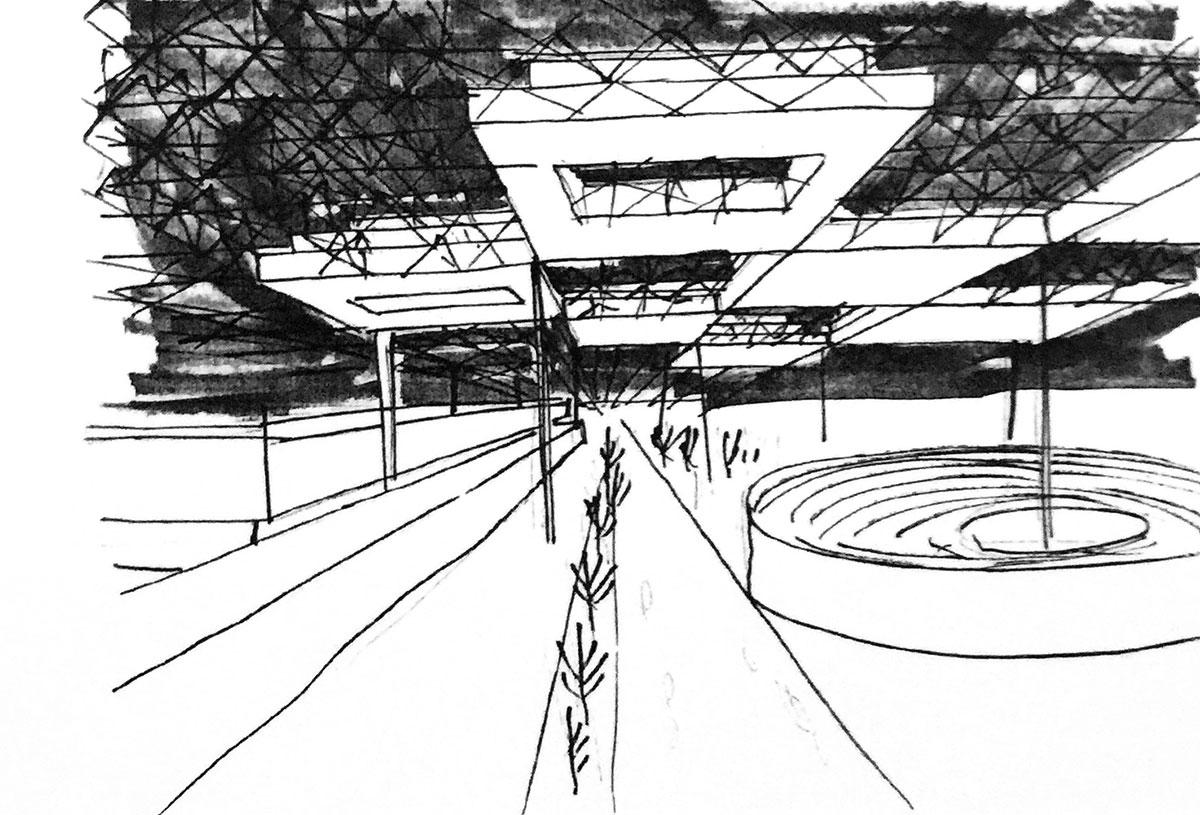

'The Cable City' by Takis Zenetos. Credit: Takis Zenetos

What can we learn from these theorists to adjust our end goals?

When I was studying architecture in Greece, I was very intrigued by Zenetos’ work, because it was so forward-looking and unlike anything I had ever seen or read. He was essentially creating architecture in order to create more leisure time and better work satisfaction for citizens. A school that he designed in Athens – it’s known as ‘The Building that Fell to Earth’ – is unlike anything else that exists in the city. His concept was focused on how to mobilise the various communities from around the school neighbourhood, how it could prepare students for a different type of adult life, with more participation in the community and with a better relation to nature.

Zenetos and Friedman were both creating what they called flexible superstructures, where nature is an integrated part of the built environment, not something separate. They also saw themselves as designing for a different type of person, a different type of human that they hadn’t seen yet. To do that, they were asking different questions of architecture: ‘What makes people happy?’; ‘How do humans connect with one another?’; ‘What supports people and transforms their lives, without compromising nature?’

'Tunis: section of the bridge-town above Medina' from 'La Ville Spatiale' projects by Yona Friedman (1959). Credit: Yona Friedman / www.yonafriedman.nl

So do we have the wrong goal for work today?

Our focus today is on how can we use technology to help us do things that we’re already doing. We have not revisited the concept of leisure or the concept of work, say, in the way that Zenetos did. These are more or less the same as they have been for the last 100 years. The one word we hear all the time in conjunction with digital technology is ‘productivity’. My interpretation of our concept of ‘increasing productivity’ today is ‘increasing profits’. That might be a benefit of what we do, but it shouldn’t define it. What if we looked at job satisfaction and asked people, ‘how can we help you be really proud of your work and your daily routine?’

Eleni Papadonikolaki, Associate Professor in Building Information Modelling (BIM) and Management at The Bartlett School of Sustainable Construction

Close

Close