Dr Olivia Arigho Stiles and Dr Adriana Suarez Delucchi (IAS/UCL Anthropocene, Indigenous Ecologies and Environmental Crisis)

28th February 2023

Dr Olivia Arigho Stiles and Dr Adriana Suarez Delucchi are two researchers who engage with the Anthropocene as part of their work in the Indigenous Ecologies and Environmental Crisis research cluster at UCL. In this blog post, they outline how the concept of Indigenous Ecologies can offer new ways of thinking about the Anthropocene.

The realisation that humans are inevitably embedded within ecosystems is not new and has been a topic for debate in scientific fora on environmental politics at least since the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment. As described by Richard H. Grove in his 1990 commentary on Nature, concerns about the environmental impacts of the colonisation of the world by Europeans were already recognised in the mid eighteen centuries by a group of European scientists.

Grove traces the current greenhouse debate to a paper presented in 1858 by Spotswood Wilson to the British Association for the Advancement of Science on "The General and Gradual Desiccation of the Earth and Atmosphere”:

‘the western-style of economic development, spread initially through colonial expansion, was increasingly seen by more perceptive scientists as threatening the survival of man himself’ (Grove, 1990, p. 14).

“

Grove sees the current awareness of a global environmental threat as the reiteration of ideas that had been discussed and – why not add – dismissed a century ago. Does it sound familiar?

The Anthropocene hypothesis has been received by some with much enthusiasm bringing the need for research on environmental governance to the forefront. The risk lies in focusing only, or perhaps too much, on the fact that we have little time to make big changes (‘urgenda’). This might lead to taking the term Anthropocene for granted and uncritically, while at the same time strengthening current institutions to deal with the planetary crisis. So, it might be worth pausing, in the midst of this urgency, to think about:

If institutions are not fit for purpose, and centralising attempts will strengthen those institutions, is this desirable? Can we think of alternatives to organise our economy and our social worlds?

The use of the word Anthropocene has been widely criticised. Some would argue that implicit in the Anthropocene ‘Anthropos’ (ἄνθρωπος, is Greek for ‘human’) is the idea of a sort of universal form of ‘human’ implying that all human beings have equally contributed to the current crisis. Others argue that the Anthropocene obscures differential responsibilities and ignores the fact that numerous communities around the world already relate quite differently to their environments.

Adriana’s work this year at the research cluster on Indigenous Ecologies and Environmental Crisis will look at efforts currently taking place in Chile where people have demanded a new constitution. There is an urgent need to replace the one left over from Pinochet’s neoliberal dictatorship (1973-1990) which privatised most aspects of life, including water.

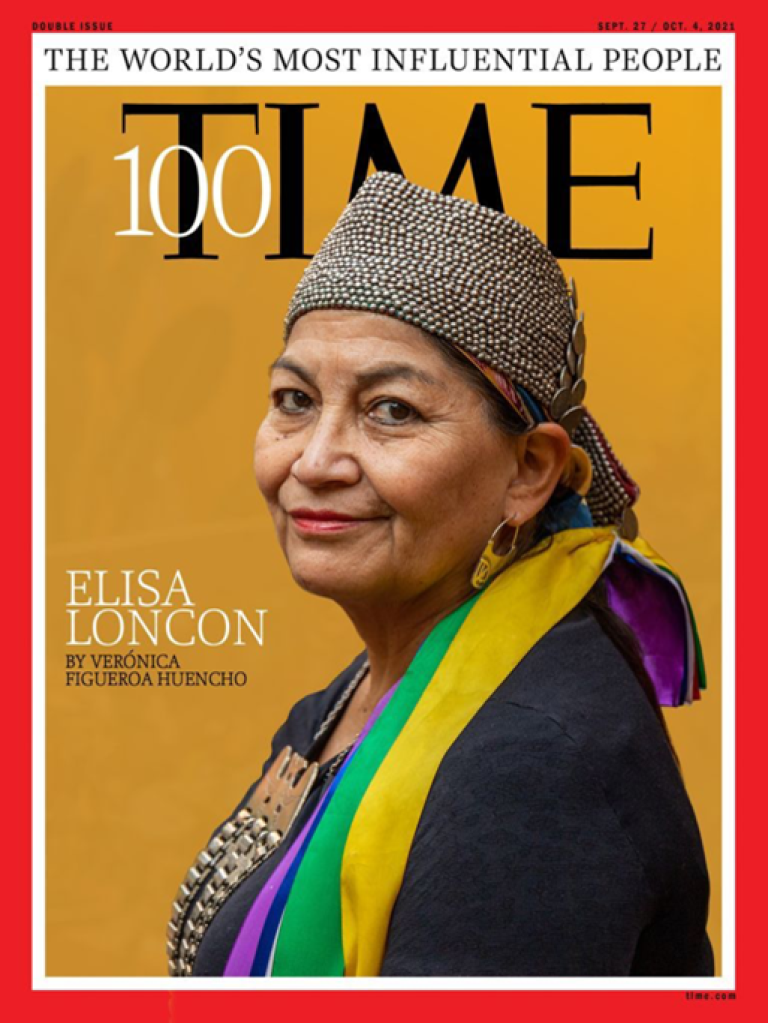

In 2021, a body was created to write the new constitution, the ‘Constitutional Convention’, formed by 155 democratically elected members, and 17 of the total were Indigenous leaders: this is an unprecedented process in Chile’s history. Elisa Loncón was elected for one of the 17 seats reserved for representatives of Indigenous peoples in the Constitutional Convention:

We Indigenous peoples participated in the Convention as independents, and we did not have longstanding political teams. We had to find the best lawyers and Mapuche and Indigenous scholars among our people to communicate our demands to a group of people who did not know about Indigenous peoples. As Convention president I had a very small team of people with political experience, unlike the members of political parties that were previously part of different governments, who had political thinktanks (NACLA, 2022).

This new constitution, while regarded as the most progressive in the world, was rejected in a national referendum in September 2022. Adriana’s aim is to learn from the efforts of traditionally excluded and Indigenous peoples, and their leaders, to influence policymaking and challenge neoliberal and modern development logics in the era of global ecological crises.

Source: TIME, Sept 27/Oct4, 2021. https://time.com/collection/100-most-influential-people-2021/6096000/eli...

Olivia’s work complements Adriana’s work on Indigenous peoples’ and the recent Chilean constitution, by looking at agrarian struggles across the twentieth century in Bolivia. What might it mean to think ‘with’ the Anthropocene in the landscapes that are now known as Bolivia? How can the Anthropocene inform our approaches to histories of struggle in the rural world?

Bolivia emerges as a paradigmatic case in the history of extractive capitalism and a useful starting point for thinking about the Anthropocene. Its highlands are home to the richest silver mine in history, the Cerro Rico (‘rich mountain’) in the city of Potosi. The intensive mining of its silver from 1545 by the Spanish resulted in dizzying wealth for the Spanish Crown; so much silver was extracted that famously silver once literally paved the streets of Potosi.

But the mining also caused massive deforestation, soil erosion, and the contamination of lands and water. It poisoned the bodies of unfree Indigenous labourers who were compelled to work in the mines, their bodies ravaged by mercury and other toxins (see Jason Moore’s article). The corrosive effects of colonial mining are still evident in the landscapes of highland mining areas, which carry high levels of deadly pollutants.

Today in Bolivia, the extractive impulse has new forms, such as the expansion of the agricultural frontier in the eastern lowlands of Bolivia. In the Santa Cruz region, soybean production accounts for 55% of all agricultural land, fueling deforestation and environmental destruction.

The entanglements of labour exploitation and ecological destruction should compel us to think about how historical agents – including the other-than-human – have experienced processes of colonisation. How have peoples living in the rural world related to the other than human – to rivers, trees, animals, mountains – in their lives and labour struggles?

In the 1970s. peasant and Indigenous organizations in Bolivia arose to mobilise against racialised oppression and class exploitation, building on longer histories of Indigenous struggle across the Andes. One important part of this included the ways in which their relationships with land and the natural world had been affected by climate change, displacement and (the absence of) state-led development in rural areas.

Today the world is confronted with multiplying incidents of ecological loss and devastation which test the limits of our approaches to nature's past. As the post-development scholar Arturo Escobar put it, ‘we are facing modern problems for which there are no longer modern solutions’.

The Anthropocene, by showing the linkages between human and non-human also poses important methodological questions for thinking about ‘who’ appears in history. How to give voice to the other-than human?

What is clear is that the scale and urgency of the planetary crisis means we need to think afresh about our relations with the other-than-human, including those in the past.

‘Protect what gives you life’ (Photo by Olivia Arigho Stiles, La Paz, Bolivia, October 2019)

Close

Close