Targeting liver immune responses to cure hepatitis B and liver cancer

To help reduce the number of people dying from HBV-related cirrhosis and liver cancer, immunologists at UCL are studying how to boost immune responses that could cure the infections.

8 December 2020

A third of the world’s population has been infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) at some point in their lives. Most people clear the infection, but the World Health Organisation estimates that at least 260 million around world have chronic infection.

Complications of chronic HBV infection like cirrhosis and liver cancer kill around 800,000 people each year, making HBV infection one of the most common causes of death worldwide.

Many babies catch the virus from their mothers during birth, while after birth children can also become infected through blood or saliva. Nine out of ten children who catch HBV before the age of five become chronic carriers.

The virus infects liver cells and if the immune system fails to clear the virus and it persists, these individuals can go on to develop liver damage and in some cases cancer.

Understanding these cell mechanisms will help us find medicines that will boost the immune system and help people to tackle HBV effectively.

“The liver is a unique organ in the way it controls immune responses,” explains Professor Maini (UCL Infection & Immunity). “It uses many different specialised cell types and pathways to become ‘immunologically tolerant’ and this can make it easier for some viruses to survive there.

“Understanding these cell mechanisms will help us find medicines that will boost the immune system and help people to tackle the virus effectively.”

Professor Maini’s team is contributing towards a ‘functional cure’ for HBV that could prevent these fatal complications. Her research focuses on how different cells that make up the body’s immune system respond to HBV infection in different groups of people: those who control the infection naturally provide a blueprint for the type of response we they are aiming to induce in those with chronic infection.

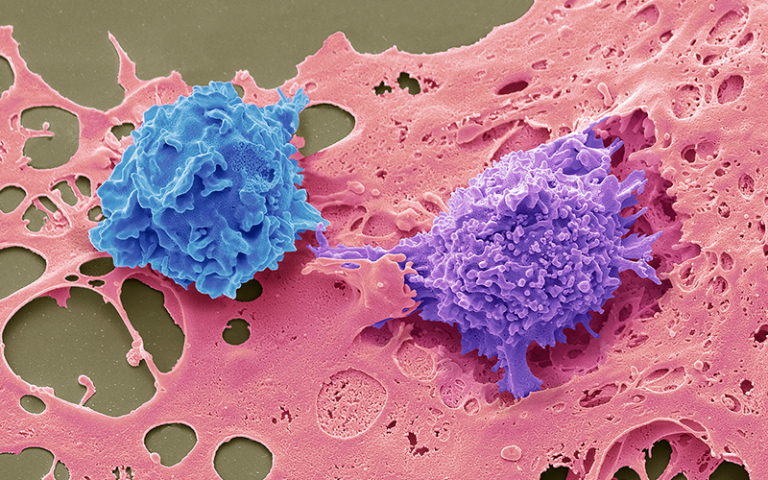

Her team is focusing on ways of increasing specialised immune cells called ‘killer T cells’, which are able to recognise and remove virally infected and cancerous cells in the body. “For example, these cells are very dependent on having the right ’food’ to function properly and we’ve shown that we can change their ability to fight hepatitis B by altering their supply of certain key nutrients,” explains Professor Maini.

“Our long-term goal is to overcome this immunological tolerance to develop therapies that can boost an effective anti-viral immune response to control the virus before liver damage occurs,” she adds.

Image

Credit: Stephen Gschmeissmer. Caption: Electron microscopy pictures showing immune cells attacking liver cancer cells

Close

Close