CAA [TEST SITE]

What is Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA)?

CAA is a build-up of a protein called amyloid within the walls of small blood vessels near the brain surface. It is a common condition, and becomes more prevalent as people get older; one recent review of all published studies found that moderate-to-severe CAA is found in around 1 in 4 people in the general older population (with an average age of 85 years). Amyloid is produced during brain activity but usually cleared. Clearance becomes less effective as we get older and amyloid builds up in the vessels.

In most people CAA doesn't seem to cause any symptoms. However, in some people the amyloid can cause leakage or blockage of small blood vessels. This can lead to brain bleeding, memory decline or seizure-like attacks, for example spreading pins and needles in the arm or face. We do not know why people develop different clinical symptoms in this disease. Research is ongoing to see if we can work out why some people with CAA have bleeding problems, while the majority do not. One possibility is that inflammation in the blood vessels could trigger haemorrhage, and we sometimes recommend specific scans in our clinic to look for this.

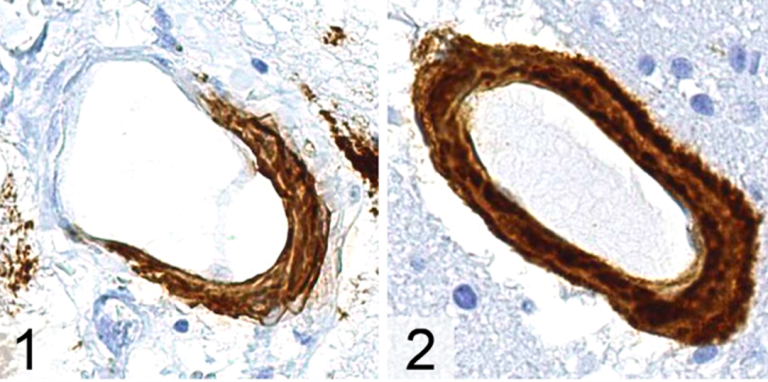

Figure: appearance of blood vessels affected by CAA, as seen under a microscope. The amyloid protein has been stained brown by a special labelled antibody. You can see partial involvement of a blood vessel wall in panel (1), and a complete involvement to affect the whole of the blood vessel wall circumference in panel (2).

CAA and bleeding in the brain

Bleeding in the brain (brain haemorrhage) is the most common symptom of CAA seen in our clinic. The bleeding can be in the brain substance or on the surface of the brain, which often presents with seizure-like attacks (usually with spreading weakness and numbness that travels up or down one side of the body, often starting in the hand and going up to the face) that we call transient focal neurological episodes (TFNE).

Globally brain haemorrhage accounts for 5% of all human deaths and causes major disability for 18 million survivors. In the United Kingdom there are around 15,000 strokes due to brain haemorrhage each year and around 180,000 people living with the effects of brain haemorrhage. CAA causes about 1 in 5 brain haemorrhages, as well as being present to some extent in many people with dementia.

Diagnosing CAA

CAA can now be diagnosed using specific types of brain scanning called magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This can detect characteristic areas of bleeding including larger bleeds (“intracerebral haemorrhage”) that cause stroke symptoms and tiny pinpoint haemorrhages called “microbleeds”. It can also detect bleeding on the brain surface, which is called “convexity subarachnoid haemorrhage”; after a few weeks, this blood on the brain surface can appear as black wavy areas called superficial siderosis (taken from sideros, the Greek word for iron, because the blood breakdown compounds contain iron from the haemoglobin protein that is found in our red blood cells).

Examples of these brain scans are shown below:

Figure: Examples of MRI brain scan (MRI) findings in CAA: (A) intracerebral haemorrhage; (B) cerebral microbleeds; (C) acute convexity subarachnoid haemorrhage (white arrow) and (D) cortical superficial siderosis.

What are the different types of CAA?

There are four different types of CAA:

- Sporadic – this is CAA that happens spontaneously, and seemingly “out of the blue”. This is the most common type of CAA, and is associated with increasing age.

- Hereditary or inherited CAA – this is a rare type of CAA which runs in families. It is caused by a change (mutation) in specific genes. This type of CAA can affect younger people (in their 40s and 50s).

- Inflammatory CAA, or CAA related inflammation - occasionally people can develop an inflammation reaction against the amyloid in the brain. This can cause a rapid decline in memory, seizures and stroke like symptoms. This rare condition often gets better; sometimes steroids or other immune drugs are used.

- Iatrogenic CAA – iatrogenic means relating to medical procedures or interventions. This type of CAA is rare has only been recently described. It is associated with specific (now banned) medical procedures involving the brain or spinal cord using certain materials donated by people after death.

FAQs

- How common is CAA?

CAA is surprisingly common; the greatest risk factor is age. One recent review of all published studies found that moderate-to-severe CAA is found in around 1 in 4 people in the general older population (with an average age of 85 years). Based on these estimates, over 15 million people in the UK might have CAA. CAA is thought to contribute to more than 4000 cases of bleeding stroke (intracerebral haemorrhage) every year in the UK alone.

- How do you diagnose CAA?

A definite diagnosis of CAA requires brain tissue (e.g., by obtaining a biopsy). Thankfully there are now non-invasive ways to diagnose CAA. This involves an MRI brain scan with special sequences to look for evidence of previous haemorrhages (bleeding) in the brain (microbleeds), or on its surface (cortical superficial siderosis). A lot of research is looking into the most accurate way to detect CAA on brain scans. CAA has become easier to diagnose and study in recent years due to the development of specific diagnostic criteria (called the Boston criteria version 2.0) that use the characteristic brain scan features to accurately diagnose CAA. Researchers are also testing criteria that allow CAA to be diagnosed using another type of scan, called a CT scan; these criteria are called the Edinburgh criteria.

- Can CAA be prevented or treated?

Research is going into developing a treatment to reduce amyloid deposition in the blood vessels, for example by reducing the production or improving its clearance. There are also studies investigating why only some people with CAA suffer brain bleeding. However, as yet we do not have a specific treatment for CAA.

Nevertheless, we can reduce the risk of recurrent brain haemorrhage in CAA by controlling ‘risk factors’. Keeping blood pressure very well controlled (e.g. under 130/80mmHg) is really important and is based on previous research studies showing that a blood pressure target is associated with the lowest risk of future bleeding without causing serious side effects. We also usually suggest avoiding blood thinning medications, such as Aspirin, Clopidogrel, warfarin or other anticoagulants such as the Direct Oral Anticoagulants, or DOACs). However, in certain conditions (such as atrial fibrillation, which is an irregular heartbeat), an anticoagulant might be considered in someone with CAA.

For those with cognitive decline (memory and thinking problems), a category of treatments called cholinesterase inhibitors (often used in Alzheimer’s disease) have shown promise in very small studies.

Transient focal neurological episodes (TFNE) can sometimes improve (reduced frequency or severity) with some anti-epileptic drugs.

- Will I develop Alzheimer’s disease after being diagnosed with CAA?

Some people with CAA do develop a decline in their memory and cognitive abilities. This is different to Alzheimer’s disease although they are related. Whilst almost all people with Alzheimer’s disease have CAA, less is known about how common Alzheimer’s disease changes in the brain are in people with CAA. In the clinic, brain scans and neuropsychological tests can be used to assess whether Alzheimer’s disease changes are likely to be present. If so, we may recommend trying a drug treatment (a cholinesterase inhibitor) to see if this improves the cognitive difficulties.

- Is CAA the same as Amyloidosis?

Amyloidosis is a word used to describe abnormal deposition and accumulation of protein in body tissues. Amyloid deposits are made up of protein fibres known as amyloid fibrils, which are formed when normally soluble body proteins aggregate (stick together in clumps) and then remain in the tissues instead of being safely removed. About 30 different proteins are known to form amyloid deposits in humans. CAA is a form of ‘localised amyloidosis’ which only affects the blood vessels of the brain, and not affect other organs in the body.

- If I am diagnosed with CAA will this affect other members of my family?

It is highly unlikely that other members of your family will be affected by CAA, as it is nearly always what is called a ‘sporadic’ (i.e., non-inherited) condition. There are however some very rare genetic forms of CAA, the commonest of which mainly affects people from a certain part of the Netherlands (sometimes called ‘Dutch-type’ CAA). CAA cannot be passed between people during usual activities of daily life.

Cognition and mood

Changes to thinking skills (“Cognition”) are common in people with CAA. Cognitive changes are particularly common following a stroke due to CAA-associated haemorrhages but can occur even in those who have not had a stroke. The type and severity of cognitive changes varies between individuals greatly. Sometimes changes can be subtle and can be missed, particularly when there have been other more obvious neurological changes. A detailed neuropsychological assessment by a trained Clinical Neuropsychologist is often the best way to help characterise and monitor one’s cognitive strengths and weaknesses. Information gained from these personalised assessments can be used to guide understanding for the person with CAA as well as for their next-of-kin. Common cognitive functions that can be affected following CAA include:

Executive functions

‘Executive functions’ is an umbrella term for higher-level thinking skills including planning and organizing, flexible thinking, multi-tasking and abstract reasoning. Patients with executive difficulties may find it harder to take on new activities or challenges because they don’t know where to begin, miss or jumble up steps when doing complex tasks like making dinner or paying the bills, find it hard to follow conversations, and/or get stuck when problems occur because it’s hard to shift perspective.

Speed of Information Processing

This refers to how quickly one is able to take in and process information. In everyday life, slowed processing speed may result in it taking much longer to think about something or to do even simple tasks. Sometimes this can lead to what feels like memory problems because your brain is not quick enough to take in and process all of the new information that you are trying to learn. It can also look like difficulty keeping up in conversations, particularly in groups or new situations, which can lead to reductions in social participation.

Memory

Patients with CAA often report difficulty with forming new memories. For example, they may find it more difficult to remember upcoming appointments, exact details of conversations they’ve had, or things they’ve done recently. In contrast, memory for personal events in the distant past such as from childhood or early adulthood tends to be relatively preserved. Memory problems can result from changes in the brain’s ability to take in relevant information, store the information and/or retrieve it later on.

Language

Patients with CAA may find it difficult sometimes to think of words in a conversation. They might know what they want to say, but the word seems to be ‘lost’ and it takes a while, sometimes days, before the word comes back. In day-to-day life, difficulties may also appear as taking longer to think of new topics or come up with ideas in conversation. Other language problems such as forgetting what words mean, difficulty speaking or understanding speech, and/or changes in reading and writing, tend only to occur after a stroke to the left side of the brain.

Visuo-perceptual processing

Visuo-perceptual processing refers to how the brain processes what the eye sees. Changes in visuo-perceptual processing can sometimes be mistaken for problems with the eyes. Common symptoms of visuo-perceptual problems include difficulty recognizing objects or faces, difficulty in judging distances or speed, making errors when picking things up or dropping things, new difficulty using technology such as mobile phone apps, and trouble reading.

Mood

As well as cognitive changes, CAA can often affect one’s mood. Mood difficulties are very common in CAA and after stroke. Patients often express worries about the future, difficulties with adjusting to new neurological symptoms, difficulties adapting to cognitive changes, wanting to withdraw from social or other life roles, a loss of interest in previous activities, sadness and loneliness, feelings of hopelessness and/or an inability to cope. Of course, some degree of psychological distress is entirely normal given the circumstances. However, when mood problems persist and/or get worse over time, it’s important to seek formal psychological support or counselling. Long-term mood symptoms can have a direct impact on your health and cognition.

Living well with CAA, keeping healthy, and managing risk factors

It can be very daunting when you are given a diagnosis of CAA, but there are steps you can take to keep healthy, which is important for your future wellbeing. People with CAA have a risk of future intracerebral haemorrhage (bleeding in the brain) of around 5-10% per year, but this can likely be reduced by prevention measures. We have found that recurrent brain haemorrhages can also be followed by long periods of stability without problems in some people with CAA.

We call things that put you at risk of further bleeding events due to CAA ‘risk factors’. These risk factors may be non-modifiable (such as your age) but some are modifiable. These modifiable risk factors include high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol levels, smoking, excess alcohol consumption and a sedentary lifestyle. However, the management of these risk factors through lifestyle modifications and medication can lead to overall improvements in your general and vascular health and wellbeing and may help to reduce your risk of further haemorrhagic events due to CAA.

- Blood pressure management

Keeping blood pressure very well controlled is the mainstay. We aim for a blood pressure reading to be below 130/80mmHg at all times if possible. A simple way to ensure that your blood pressure remains well controlled is to invest in a blood pressure monitor which are commonly used and means that you can use them at home easily.

- How to take your blood pressure at home

When using a blood pressure monitor at home the following guidance is useful. Firstly, there are lots of things that can elevate your blood pressure for short periods. These include smoking a cigarette, exercising, needing the toilet, or drinking a caffeinated drink. Do not wear restrictive clothing, do not cross your legs, and use the same arm when taking your blood pressure ensuring that it is supported.

When taking your blood pressure ensure you are in a relaxed state and do not talk to anyone when you are taking a measurement. You should aim to take 3 blood pressure measurements at least a minute apart and record the lowest of these 3 readings in a home blood pressure diary. We advise you to take your blood pressure on a weekly basis, however, if you have been told by a health care professional that they are concerned that your blood pressure is high, then we advise taking measurements on a daily basis (once in the morning and once in the afternoon or evening) for 2 weeks and then discuss the results with your GP.

- Smoking

Smoking results in acute rises in blood pressure and this is particularly dangerous in those who already have high blood pressure.

Therefore, smoking cessation can lessen the risk of further haemorrhagic events due to CAA. Most GP surgeries and pharmacies will offer smoking cessation services, or you can access more information from the NHS website.

- Alcohol consumption

We know that excess alcohol consumption increases your risk of stroke due to brain bleeding, although the exact reasons for this are unknown. It is possible that alcohol affects blood pressure, indirectly increasing stroke risk, but it might also have other effects that increase brain bleeding risk. The recommended guidelines for alcohol consumption in both women and men are 14 units per week. Putting that into context, a 175ml glass of wine or a pint of standard beer both contain about 2 units (depending on how strong they are). However, to reduce your overall risk of further brain haemorrhage as much as possible, we often recommend avoiding alcohol altogether.

- Diet

It is important to consume a healthy diet to maintain cardiovascular health. The current guidelines are to:

- Eat at least 5 portions of a variety of fruit and vegetables every day

- Base meals on higher fibre starchy foods like potatoes, bread, rice or pasta

- Have some dairy or dairy alternatives (such as soya drinks)

- Eat some beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat and other protein

- Choose unsaturated oils and spreads, and eat them in small amounts

- Drink plenty of fluids (at least 6 to 8 glasses a day)

- Eat foods high in fat, salt and sugar less often and in small amounts

- Exercise

Physical inactivity and obesity are significant risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Moderate to vigorous physical activity for primary stroke prevention can lead to decreased blood pressure, LDL cholesterol and will help with weight loss. The current guidelines from the UK Chief Medical Officers Physical Activity Guidelines state that adults should try to be active every day and aim to do at least 150 minutes of physical activity over a week, through a variety of activities. We would advise to avoid all types of contact sport where you are likely to hit your head.

There may be barriers to physical activity after stroke. These can include deconditioning, physical impairment, depression, and low motivation but despite these challenges physical activity is important but should be conducted under supervision initially.

- Blood thinning and other types of medication

We recommend that you try to avoid all medicines that “thin the blood”, as these increase bleeding in general.

These medications include:

- Antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin, clopidogrel and dipyridamole

- Anticoagulant drugs such as warfarin, and non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOACs) such as dabigatran, apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban and heparin.

We also recommend avoiding prolonged use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as Ibuprofen, as these might also increase bleeding.

Sometimes, however, there may be a strong indication for a “blood thinning” medication. This may include instances such as a high risk of future strokes or heart attacks due to blood clots. These types of medications may sometimes be recommended to people with a history of brain bleeding but under specialist advice.

We recommend that you check any over-the-counter medications before use, for example hay fever, common cold or allergy treatments, because these can include substances which might increase your blood pressure. If you have questions, please ask the pharmacist prior to use.

Certain recreational drugs increase the risk of stroke and can increase blood pressure. We advise that people with CAA avoid using any recreational drugs for these reasons.

Our clinic at NHNN

We offer a multidisciplinary outpatient specialist service for anyone that has been diagnosed with or is suspected to have CAA.

The one stop clinic day will consist of assessments and investigations on the day, including a brain scan, neuropsychological (cognitive) tests, a heart scan (echocardiogram), and blood tests, followed by a consultation in the afternoon with one of our specialist consultant neurologists to go through the results.

The service is NHS led and we can only see you if you have been referred to us by your GP or local specialist.

All referrals to the clinic should be addressed to Professor David Werring, The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square, London WC1N 3BG.

Research in Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy

At present, we do not know of any way of preventing or curing CAA. We do not know why CAA develops in some people but not others, or why only some people with CAA suffer haemorrhage (bleeding) within or around the brain. Research in CAA will help us to answer these questions and help us to find treatment targets for CAA.

As well as research specific to CAA, there are research studies investigating bleeding strokes which might be relevant.

A list of trials currently underway at our centre can be found here: [link]

If you are interested in participating in research in CAA, or would like more information, please contact us on [telephone] or [email].

Ways in which people with CAA might take part in research include:

treatment trials

There are projects (sometimes called clinical trials) in which potential treatments for CAA are tested.

Observational studies

These are projects where no treatment is offered as part of the study. In our clinic we undertake observational research on the routinely collected clinical tests from people who attend, including brain scans, as part of a process of continual assessment and improvement in our service (for example, looking at better ways to diagnose CAA). If you object to your clinical information being used in this way, you can let us know. We will never share or publish information that identifies you without your explicit (specific) consent.

Examples include biomarker studies, which are looking for new measures of CAA that might be early markers of disease, or associated with particular patterns of disease, or can provide information on prognosis. People with CAA involved in studies like this might have blood tests, brain scans and other tests to look for these new markers.

Brain donation

Some people with CAA choose to donate their brains after they die. These donations allow specialist researchers (neuropathologists) to perform detailed assessments of where CAA has developed and how severe it is and can provide information on the processes that lead to CAA.

Patient written testimony

I was diagnosed with CAA after having a sudden bleed in my brain in the early evening of February 2nd, 2021. The background to this was that I had been working especially hard organizing a large international conference in my field. I was aware that I was considerably more anxious than usual. During the day I noticed that, peculiarly, I didn’t remember how to do ordinary things on my computer: I suddenly didn’t know how to send invoices, something I’d done automatically for many years. I was shocked about this, and told my husband, but I think I was also profoundly denying the seriousness of such a sudden incapacity. Later in the evening, as we were reading in bed, I suddenly got an extremely bead headache, unlike anything I’d ever experienced. My husband insisted on calling 911 and I was advised to go immediately to Emergency at the local hospital. I had a brain scan and was given the diagnosis of CAA some hours later. I was aware that my mind was not working properly.

Having received the diagnosis of CAA a local neurologist looked at my test results and after a long consultation she brought the details of my case to Professor Werring's attention. I had a telephone conversation with Professor Werring some months later and was given an appointment at the clinic about six months after that.

Being at the clinic, after such a long wait, was very much easier and more pleasant than I’d expected. I was immediately met by a nurse who told me she would guide me through the long day of meetings, which she did. I found some of the ’tests’, very testing…. mostly the mathematic ones. It was distressing to realize that i couldn’t do things I’d always found perfectly easy: mathematical problems that required being able to think through several steps in my mind. I eventually had to just give up on those, to say I just can’t do this. The other tests - presented to me by other physicians - were easier for me to do, not always EASY, but easier. All the people I came in contact with were pleasant and very kind, and I found I was able to talk to each of them - to ask questions - which sometimes they couldn’t answer - but also to describe the experience I was having to them. They seemed willing to engage in conversation about what was going on, and my experience of it, in a friendly way. This was most reassuring. I didn’t feel like a weird, strange non-person.

It was terrifying to be diagnosed with CAA. At first, I looked all over the web for some information that would reassure me: I didn’t find any. I was tempted to continue looking for someone somewhere who would promise a cure, or at least a treatment, but I soon stopped looking. When I spoke with Professor Werring and he said there is no treatment and no cure, it was a terrible blow. I can’t believe anyone would be sanguine about getting the diagnosis of Cerebral amyloid angiopathy. However, several things happened over the year in which I awaited my appointment day at the clinic.

I was told by several medical friends that the acute anxiety I often felt - with accompanying mistakes in memory particularly - was not to do with my brain, but with my mind: that is, it was to do with completely expectable feelings of anxiety which were not about my actual brain not-functioning. This was a huge help to me. And my experience really confirms this: after my meeting with the team at the clinic, although the diagnosis wasn’t changed at all, I noticed that I am sleeping much better, thinking much better, getting on with my life in a much less anxious and disturbed way.

So, my advice to anyone diagnosed with CAA is to recognize that of course you feel anxious and frightened, but that is a consequence of having a worrying diagnosis; it isn’t a statement that you are going to be seriously impaired. Follow the instructions you’ve been given I’m not having even the occasional glass of wine, and I keep exercising with long walks, and keep on doing all the things I enjoy doing. I hope I will go on feeling this well for a long time.

Close

Close