Cognitive differences linked to amyloid at age 70

31 October 2019

People with more harmful amyloid plaques in the brain already score worse than their peers on cognitive tests at age 70, finds a new UCL-led study.

Amyloid plaques are implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, which typically develops multiple years later, so the new findings, published in Neurology, might show early warning signs before any disease develops.

“Our study found that small differences in thinking and memory associated with amyloid plaques in the brain are detectible in older adults even at an age when those who are destined to develop dementia are still likely to be many years away from having symptoms,” said lead author Professor Jonathan Schott (UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology).

The study participants have been tracked since birth in the world’s longest-running cohort study, so the research team was also able to see how test scores compared to childhood tests.

Higher cognitive test scores at age eight, as well as increased education and socioeconomic status, predicted thinking and memory performance at age 70. The effect was independent of amyloid deposition in the brain, and therefore does not suggest that dementia risk is related to childhood test scores.

The study involved 502 people all born during the same week in 1946 in Great Britain, who are part of the Medical Research Council National Survey of Health and Development, housed within the MRC Unit of Lifelong Health and Ageing at UCL.

The study participants, who form the Insight 46 subset of the cohort study focused on brain changes, took thinking and memory tests between the ages of 69 and 71. For example, one test involved looking at various arrangements of geometric shapes and identifying the missing piece from five options. Other tests evaluated skills like memory, attention, orientation and language.

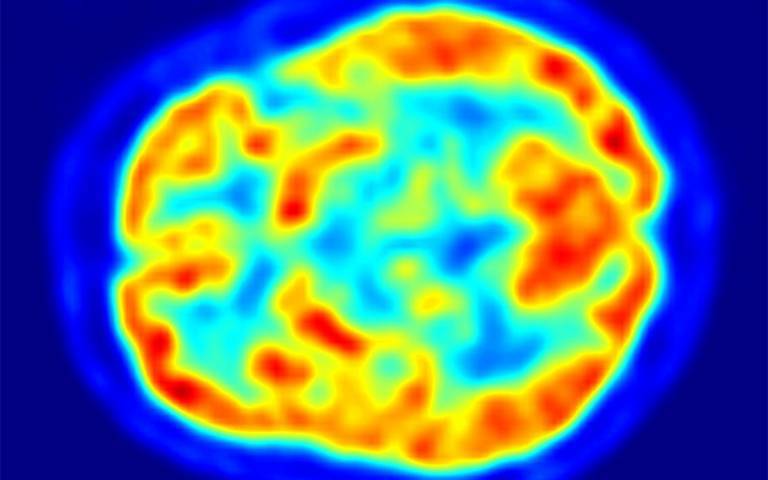

They also had positron emission tomography (PET) scans to see if they had amyloid plaques in the brain, as well as detailed brain magnetic resonance imaging scans (MRI).

Researchers found that participants with amyloid plaques had lower scores on cognitive testing at age 70 than their peers who did not have amyloid build-up. For example, on the missing pieces test, they scored 8% lower on average.

However the presence of these plaques was not associated with sex, childhood cognitive skills, education or socioeconomic status.

As the study participants had completed similar cognitive tests at age eight, the research team found that childhood thinking skills were associated with scores on the memory and thinking tests taken more than 60 years later. For example, someone whose cognitive performance was in the top 25% as a child, was likely to remain in the top 25% at age 70.

As the effects were independent amyloid deposition, low scores did not indicate a person would develop dementia. As the new study only looked at one late-life time point, the researchers could not draw conclusions about cognitive decline over time.

Even accounting for differences in childhood test scores, there was an additional effect of education. For example, participants who completed a college degree scored around 16% higher than participants who left school before the age of 16.

Having a higher socioeconomic status, determined by occupation at age 53, also predicted slightly better cognitive performance at age 70, but the effect was very small. For example, those who had worked in professional jobs tended to recall an average of 12 details from a short story, compared to 11 details for those who had worked in manual jobs.

Women performed better than men in tests of memory and thinking speed.

“Our study found that childhood cognitive skills, education and socioeconomic status all independently influence cognitive performance at age 70,” said Professor Schott.

“If we can understand what influences an individual’s cognitive performance in later life, we can determine which aspects might be modifiable by education or lifestyle changes like exercise, diet or sleep, which may in turn slow the development of cognitive decline.”

“Continued follow-up of these individuals, and future studies are needed to determine how to best use these findings to more accurately predict how a person’s thinking and memory will change as they age,” he said.

Dr Carol Routledge, director of research at Alzheimer’s Research UK, which funds Insight 1946, said: “This study sheds more light on the complex relationship between memory and thinking skills in early life and our cognitive ability as we get older.

“One explanation for this relationship is cognitive reserve, the idea that the memory and thinking skills we acquire during our lives can make us more resilient to the symptoms of dementia in older age, but more research is needed to better understand this link.

“Research shows up to a third of dementia risk may be within our power to change, with evidence suggesting that eating a balanced diet, staying physically and mentally active, keeping blood pressure and cholesterol in check and not smoking are all ways to keep our brains healthy,” she said.

The study was supported by Alzheimer’s Research UK, the Medical Research Council Dementia Platform UK, the Wolfson Foundation and Brain Research UK.

Links

- Research paper in Neurology

- Professor Jonathan Schott’s academic profile

- UCL Dementia Research Centre

- UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology

- MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing at UCL

- MRC National Survey of Health and Development

- Insight 46 study

Image

- PET scan of human brain (not from this study). Credit: Jens Maus, Source: Wikimedia Commons

Source

- Neurology

Media contact

Chris Lane

Tel: +44 (0)20 7679 9222

Email: chris.lane [at] ucl.ac.uk

Close

Close