FMS Symposium report: Sustainability and the Environment

24 April 2018

Komal Bhatia reports on the first session of our March 2018 symposium, which discussed food security, sustainability and the environmental impact of food production.

Komal Bhatia summarises and reports on the first session of our March symposium on Food and the Planet.

Komal Bhatia is a PhD student and researcher at the UCL Institute for Global Health.

This is the first in a series of four write ups of Food and the Planet: the 2nd Annual Symposium of the UCL Food, Metabolism and Society Research Domain, which took place on March 21 2018.

Are we courageous enough now to make decisions about the environment, sustainability and health that in a hundred years’ time will be seen as brave? Can we resist putting knowledge into ever smaller boxes, and draw on the breadth of ideas that can shape the future?

“We live in exciting times!”, said Sir Tim Smit, co-founder of the Eden Project, in his opening keynote at the FMS 2018 Symposium, asking the audience to think broadly about solutions to ecological problems and challenging scientists to tackle the big sustainability questions head on. Sir Tim’s inspiring comments on the power of political leadership to address food and farming issues were followed by a stronger remark about the need for scientists – early in their careers as well as those with decades of experience – to get better at science communication to translate their ideas into relevance for the general public.

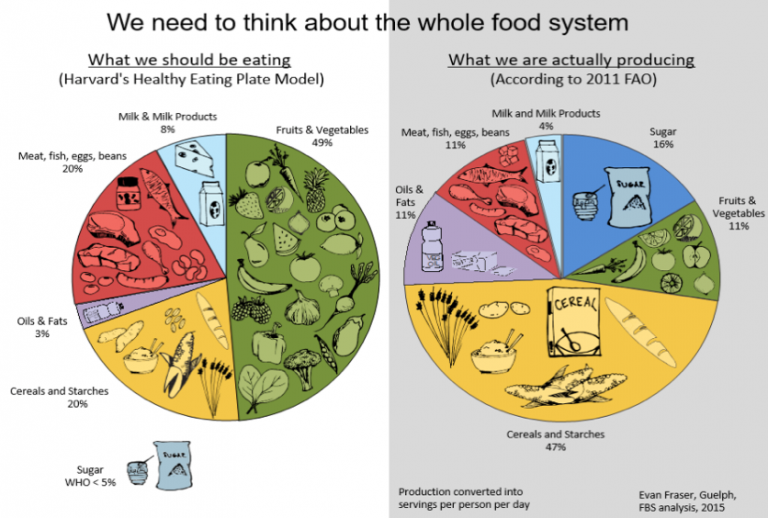

This thought provoking keynote was put into broader context by Global Food Security’s Riaz Bhunoo who provided an excellent summary of the scale of the global food security challenge and the urgent need to adopt a food systems approach for sustainable health. We face the twin tasks of producing more food than ever before and addressing the health needs of 700 million people who will be living with diabetes by 2025. Preventative action to stem the rise in diet-related diseases seems vital in the face of rising healthcare costs, and is spurred by the unrelenting and deleterious consequences of climate change on nutritional quality and yield of food crops. A sustainable food systems approach can help us find ways to fix the mismatch between what we need to eat for optimal nutrition and what we currently produce. Climate change agreements and targets play an important role in shaping our thinking around this problem: if emissions-heavy and unhealthy agricultural systems could be modified to take up a smaller proportion of carbon quotas, there would be more room for other sectors. We must make changes along the parts of the food system that will have the most impact on nutrition and sustainability. Such holistic thinking would help embrace diversity in food production and consumption, and move towards healthier food environments and systems that are resilient to climate shocks.

Food production relies on the intensive use of limited resources – agriculture accounts for 70% of freshwater withdrawals, 38% of land use, and 25% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Carole Dalin, based at the UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources, fleshed out pressing technical challenges in her talk on measuring the environmental sustainability of global food production and trade. Agriculture influences the environment through resource use and emissions, and the environment affects agriculture through the ecosystems of goods and services. Solutions aimed at preserving this delicate balance within environmental limits must be supported by strong and innovative metrics to assess progress in outcomes and track changes. These metrics need to integrate several aspects – like land, water, and fertiliser and carbon intensity of crops – to avoid trade-offs, evaluate sustainability of crops in terms of how long it would take to replenish exhausted resources, and link consumption with production by tracking global food trade and its role in resource depletion. Carole’s introduction to environmental limits set the stage for the next talk.

Marco Springmann from the Oxford Martin Programme on the Future of Food addressed the planetary boundaries, or the safe operating space for humanity, of expanding food systems trying to meet the increased demand that comes with population growth and rising incomes. Between 2010 and 2050, the environmental impacts of food systems could rise by 60%-90%, putting ecosystems at risk. Transgressing planetary boundaries could also affect food availability, with the greatest negative impact on protein- and micronutrient-rich animal source foods. Silver-bullet solutions will not be enough; Marco’s analysis of projected outcomes of possible strategies highlighted three areas where action would be most effective. A reduction in food waste, ambitious technological changes, and a shift towards more plant-based diets would go a long way towards mitigating the growing environmental stresses of food systems.

The session’s speakers convened for a lively panel discussion chaired by Richard Pearson from the UCL Centre for Biodiversity and the Environment. Questions from the audience sparked an energetic debate on the conflict between academics’ role in scientific research and their potential involvement in political advocacy, and the ways in which researchers can navigate that conflict reflexively and carefully. But a consensus was evident on the need for wider, and more creative public engagement activities to disseminate scientific research on sustainability, health and nutrition.

Close

Close